TORONTO -- More than two people each day are dying of opioid overdoses in Ontario, a grim tally that underscores the soaring use and abuse of the potent narcotics, researchers say.

The rate of opioid-related deaths in the province has almost quadrupled over the last 25 years, skyrocketing to 734 in 2015 from 144 in 1991, says a report published Thursday by the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network.

"What we also found really interesting was the types of opioids involved in those deaths and how those have changed over time," said lead author Tara Gomes, a scientist at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto.

Prior to 2012, oxycodone was the most common culprit in opioid-related deaths. But with the introduction of a tamper-deterrent formulation of the drug that year, oxycodone's involvement in these deaths declined, while other opioids were found to be increasingly implicated in fatal overdoses.

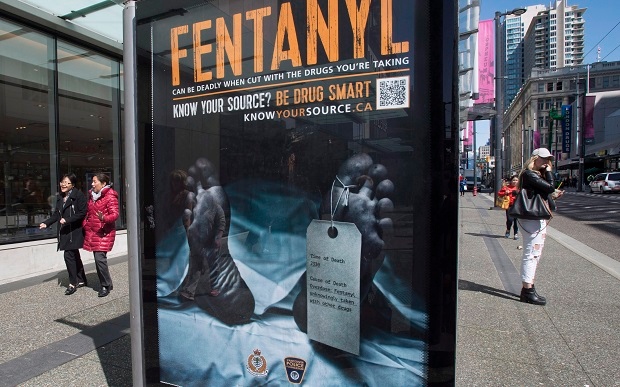

"What we've seen is that fentanyl, hydromorphone and even heroin involvement in opioid-related deaths really started to rise at that point in time," said Gomes.

"That's a bit concerning because it means that simply changing access or the formulation of one type of opioid isn't actually leading to the ultimate goal of reducing the rate of opioid-related deaths in the province," she said. "It's simply shifting people between the types of opioids like fentanyl and heroin."

Fentanyl's contribution to opioid-related deaths soared by 548 per cent between 2006 and 2015, and it is now the most common cause of lethal overdoses among this class of powerful painkillers. Fentanyl can be obtained in both prescribed patches and illicitly manufactured pills, but the latter have only been around for the last couple of years.

"What we don't know in Ontario is the degree to which the illicit form of fentanyl is really driving the increases we're seeing, compared to fentanyl patches that are being prescribed by physicians and then diverted onto the street," said Gomes, adding that B.C. has witnessed "an enormous rise" in illicit fentanyl deaths in the last two years.

Hydromorphone is the second most commonly identified drug in Ontario's rash of overdose deaths -- with its involvement climbing by 232 per cent between 2006 and 2015 --while heroin's connection to opioid-related fatalities jumped by 975 per cent, despite small numbers overall.

The report, based on 1991-2015 data obtained from the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, shows that opioid-related deaths often involved other drugs that could have contributed. Post-mortem toxicology identified benzodiazepine in more than half of those who died and cocaine in almost one-third.

"The presence of these other drugs may be indicative of the concerning practice of combining cocaine with illicitly produced fentanyl, which is relatively inexpensive, to extend the drug supply," said Gomes.

"And we're seeing a fair amount of stories about people using cocaine who end up dying of a fentanyl overdose because they don't realize they're taking an opioid and may never have been exposed to an opioid before," she said. "They may have simply been cocaine users."

The report also shows that more than 80 per cent of all opioid-related deaths in 2015 were accidental, while the remainder were suicides. A break-down of accidental deaths by age showed that almost 60 per cent occurred among youth and younger adults, aged 15 to 44, and more often among males.

Almost 80 per cent of opioid-related suicides occurred among older adults, aged 45 years and older, with women outnumbering men.

The researchers said opioid-related deaths occur among both sexes, all ages and all income brackets. However, on average, individuals who died of an opioid-related cause in 2015 were men, middle-aged and living in lower-income, urban settings.

Opioid-related deaths in Ontario now exceed the number of those killed in motor vehicle accidents, said Gomes, noting that in 2014, there were 676 fatal overdoses in the province compared to 481 road fatalities.

"It does highlight how pervasive this issue is becoming in society," she said. "So we now need to figure out how we can avoid people dying from opioid-related causes."

Gomes said it will need a multi-pronged approach, including altering doctors' prescribing patterns to prevent people becoming addicted to the drugs, while helping those who are already dependent on the painkillers to pare down their medicinal use without driving them toward more dangerous forms of illicit opioids.

She said other public health measures need to include increased addiction treatment programs, harm-reduction strategies such as safe-injection sites, and more widespread access to the overdose-reversal medication naloxone, "so we can avoid some of the fatal consequences of these drugs."