TORONTO -- Ontario health officials say that while COVID-19 cases continue to climb, modelling data indicates the province may have avoided the worst-case scenario.

At the same time, officials say they expect to see at least 800 new COVID-19 cases a day for most of the next month.

“What is important here though is that although cases are continuing to grow, that growth has slowed,” co-chair of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table Adalsteinn Brown said at a news conference. “We’re starting to see a more gentle curve there.”

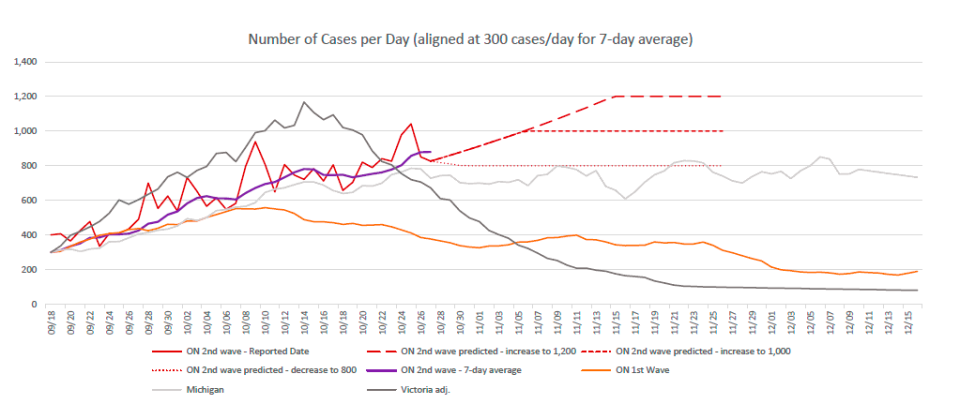

Provincial health officials released modelling data on Thursday showing three different scenarios for Ontario’s second wave of COVID-19.

In the worst-case scenario, officials said the province could see its seven-day average rise to 1,000 or 1,200 cases a day for most of November. The best case scenario would see about 800 new COVID-19 cases a day.

Previous projections, released late September, showed the province could see 1,000 new COVID-19 cases daily by mid-October.

Ontario recorded more than 1,000 new infections in a single day for the first time on Sunday. Since then, the daily case count has fallen below the quadruple-number mark.

There were 851 new cases logged on Monday, 827 on Tuesday, 834 on Wednesday and 936 on Thursday.

Ontario not expected to exceed ICU threshold for COVID-19 patients

According to the data presented on Thursday, the province is not expected to exceed the 150-bed threshold for COVID-19 occupancy in intensive care units (ICU) in the next month, unless the situation gets rapidly worse.

The provincial government has previously said that when there are less than 150 COVID-19 patients being treated in intensive care in Ontario hospitals, the province can “maintain non-COVID-19 capacity and all scheduled surgeries.”

Once the number rises above 150 it becomes harder to support non-COVID-19 needs, the government said. Once it exceeds 350 people, it becomes “impossible” to handle.

Furthermore, according to the data, there has been a 56 per cent increase in confirmed COVID-19 bed occupancy in the province over the last three weeks. The majority has not required treatment in intensive care.

Officials said they now only expect to exceed 150 COVID-19 patients in the ICU within the next 30 days “in the worst-case scenario.”

Brown stressed that while growth has slowed, the data does not show that COVID-19 cases have peaked or that Ontario is on a downward curve.

“We're just getting to a slower period of growth within that curve. It's going to be critical to level up public health system capacity across every public health unit to be able to respond effectively to the disease and control the spread.”

‘Sharper increase’ in cases, deaths in long-term care

Brown went on to state that despite avoiding the worst-case scenario as outlined in previous projections, the spread of COVID-19 “can dramatically turn” leading to “rapid, rapid growth quite quickly.”

Long-term care homes, which were hardest hit in the first wave of the disease, are now starting to see “a much sharper increase” in cases, Brown added.

According to the province’s data, there are 396 active COVID-19 cases among long-term care residents as of Oct. 27 and 281 active cases in staff.

There has also been a “sharply increasing curve of reported deaths” in long-term care, according to Brown.

Eighty-five long-term care and retirement home residents have died after contracting COVID-19 since Aug. 15, the data showed. The cumulative death toll associated with COVID-19 in long-term care homes has surpassed 1,900 in Ontario.

“We have more deaths in the last week – 27 deaths - than we did between August 15 and October 8,” Brown said.

The data presented on Thursday did not include any death projections.

In the spring, officials said that Ontario could see anywhere between 3,000 and 15,000 deaths related to the disease.

“I believe if we keep it on the current trajectory we will see far fewer than that high-level estimate of deaths but I do worry given how quickly you have seen thing turn in a number of other jurisdictions that any prediction is going to be challenging,” Brown said.

Majority of COVID-19 outbreaks in Stage 2 regions are not in restaurants and bars, data shows

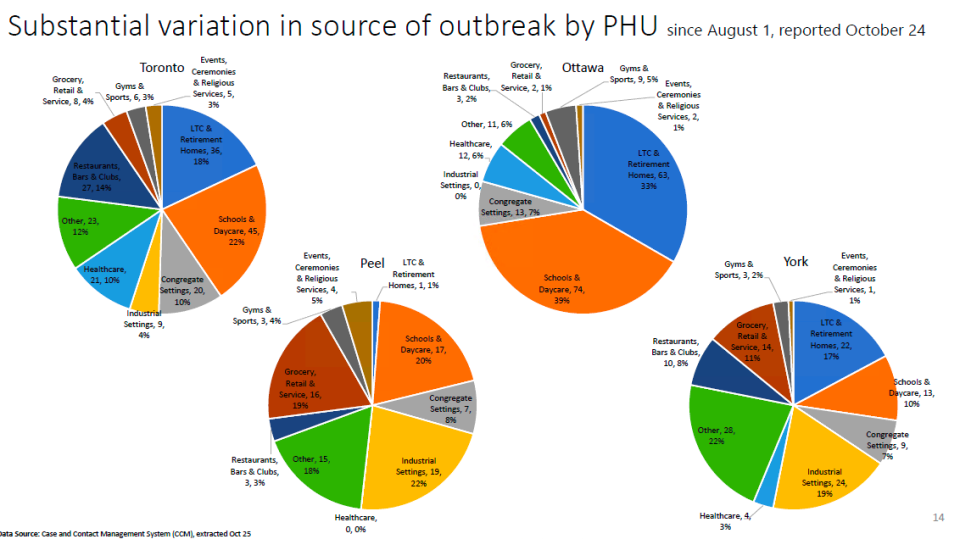

Four regions in Ontario—Toronto, Peel Region, York Region and Ottawa—have been designated COVID-19 hot spots and have been reverted back to a modified Stage 2 of the province’s economic reopening plan in an effort to curb the spread of the disease.

Under Stage 2, indoor dining has been prohibited and large facilities such as gyms and cinemas have been closed.

In the data presented on Thursday, the number of outbreaks associated with restaurants and bars since Aug. 1 appears to be much lower than the percentage associated with schools, child-care centres or long-term care facilities.

An outbreak is defined as two COVID-19 cases within a 14-day period, where both cases could reasonably be acquired at a single facility or event.

In Toronto, restaurants, bars and clubs accounted for 14 per cent of outbreaks between Aug. 1 and Oct. 24. compared to long-term care (18 per cent) and schools and daycares (22 per cent).

Gyms and sports accounted for roughly three per cent of Toronto outbreaks within that time period.

The difference becomes more drastic in other hot spots.

In Peel Region, restaurants accounted for about three per cent of all outbreaks compared to grocery and retail (19 per cent), schools and daycares (20 per cent), and industrial settings (22 per cent).

Restaurants and bars accounted for eight per cent of outbreaks in York and two per cent of outbreaks in Ottawa since Aug. 1.

When asked why restaurants, bars and gyms were closed in those four regions considering the number of outbreaks associated with the facilities, health officials said that it was based on evidence presented to their science table and the fact that those facilities are considered “social settings.”

“We were picking those settings where it's indoors, where people are unable to mask for long periods of time,” Ontario Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. David Williams said.

Williams added that facilities such as schools and long-term care homes have “proper steps and (personal protective equipment) in place.”

For his part, Brown called the data regarding outbreaks “complicated.”

“The variation in the source of outbreaks across those four public health units that had restrictions reasonably showing us that there's not one consistent pattern,” Brown told reporters at the news conference.

“There's often concern that we need to wait to see outbreaks in a particular public health unit before instituting restrictions. That would be akin to waiting to close the barn door until after the horses left.”

At the same time, there is still a large percentage of COVID-19 cases in which there is no epidemiological link to a source, particularly in the four Stage 2 regions.

The data shows that in the last seven days, about 65 per cent of cases in Toronto have not been traced back to a concrete source.

That number drops significantly in Ottawa (48.8 per cent), Durham (27.5 per cent) and Peel (16.9 per cent.)

Peel Region is reporting the highest seven-day rolling average in COVID-19 positivity rates at 6.5 per cent, followed by Toronto (4.8 per cent), York (4.5 per cent) and Ottawa (3.1 per cent).

Halton Region is teetering at a 2.5 per cent positivity rate.

More than 73,000 novel coronavirus cases have been confirmed in Ontario since the first case was detected in late January. That number includes more than 3,000 deaths and more than 63,000 recovered patients.