Could vertical farming solve Canada's food supply chain issues?

It’s a rainy afternoon in North York, the kind of weather farmers traditionally thrive on. But tradition takes a backseat to technology on Jonah Krochmalnek’s estate. Basil, cilantro and arugula grow floor to ceiling inside his 5,000 square foot warehouse. Each sprout is meticulously managed; two million seeds planted every week, harvested under purple-hued LED lights rather than rays of sunshine.

“We control Mother Nature, instead of Mother Nature controlling us,” said Krochmalnek, owner of Living Earth Organic Farm, the largest indoor certified organic farm in Ontario.

Living Earth is a microcosm of the blossoming vertical farming industry.

Vertical farming is the process of using online, automated technology to control and monitor every aspect of the growing cycle. While the technology was initially developed by NASA to produce food on cramped interstellar space journeys, it’s now being utilized here on earth, during a time when our global food supply faces a myriad of challenges.

Vertical farming software meticulously manages climate, irrigation and LED light luminance to control crop cultivation much more efficiently than outdoor or greenhouse farming, removing guess work from growing.

“The amount of water we use on an annual basis is less than five per cent of what it would be in a greenhouse,” Krochmalnek told CTV News Toronto.

“In a greenhouse, you have to water multiple times a day. We water twice per week. Our crop success rate is 99.5 per cent in terms of the yield we expect versus what we get, every harvest. That makes vertical farming very predictable,” he added.

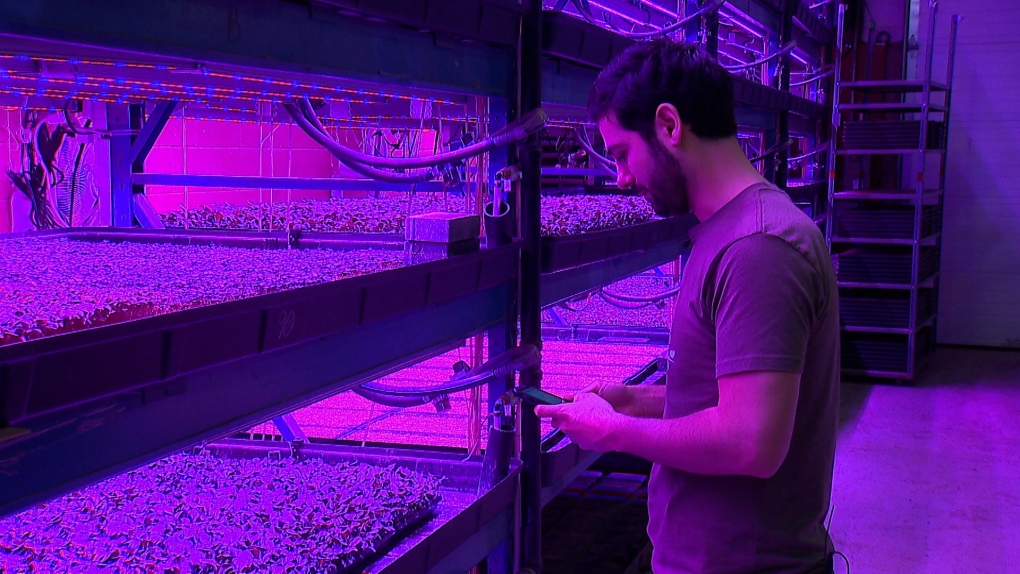

Jonah Krochmalnek, owner of Living Earth Organic Farm, is seen in this photograph. (Corey Baird)

Jonah Krochmalnek, owner of Living Earth Organic Farm, is seen in this photograph. (Corey Baird)

That predictability is a premium commodity these days. Severe droughts and wildfires last year prompted a $20 million bailout of farmers in British Columbia. The fallout from extreme weather events, and the collapse of BC’s Coquihalla Highway, a vital transportation link for Canada’s food supply, cost the province an estimated $400 million in lost economic output.

The consistent, controllable nature of the technology is drawing increased attention from major players within the grocery and retail world. Two months ago, Walmart ventured into vertical farming, partnering with Plenty, a vertical farming startup out of San Francisco.

Infarm, an Amsterdam-based vertical farming company that partnered with Sobeys Inc. in 2020, recently announced a $200 million plan to expand its operations worldwide.

Beyond climate change, there are many reasons why big business is bullish on vertical farming. With the world’s population projected to exceed nine billion by 2050, the United Nations has concluded global food production will need to increase by 60 per cent to keep pace, putting a strain on the planet’s already overtaxed freshwater reserves. About 70 per cent of the world’s freshwater is already allocated to agriculture.

In Ontario, urban development removes 175 acres of farmland every day, the equivalent of five family farms per week according to the Ontario Federation of Agriculture.

Statistics Canada warns the farming sector faces a looming labour shortage, with an unsustainable reliance on foreign workers, and a growing number of jobs going unfiltered domestically. The sector’s labour gap is predicted to balloon to more than 113,000 people by 2025.

“If we have to produce twice as much food, and we're losing freshwater and farming plains, technology has to solve that,” says Dave Dinesen, CEO of CubicFarms, a B.C.-based company that sells vertical farming equipment and software. Each CubicFarms System module is capable of producing 1,900 heads of lettuce per week.

“A truckload of salad products coming in from California is going to burn about 5000 litres of diesel. Depending on what border crossing you're at that’s 30-40 hours. You're literally paying to import compost. At least 25 per cent of these things are thrown into the compost. We are already using 100 per cent of the world's available freshwater for people in agriculture. That can't continue. It has to change. Wouldn't it be nice to know that a significant amount of our food is grown in our country?”

The potential for stabilizing and localizing our food supply has piqued the interest of Bronwyn Scrivens, an industrial real estate broker based in Edmonton. She’d like to see unused commercial property converted to vertical farms.

“We have a 21.22 per cent office vacancy rate in Edmonton. In Calgary it’s just over 30 per cent vacancy in our office towers,” Scrivens told CTV News Toronto. “I know it's a bit of a romantic idea that we can put these vertical farms in office towers and kind of have a more euphoric use of space, but it’s not just a pipe dream. I think it requires a lot of creativity and risk tolerance to get into this realm because it hasn't been done much.”

Dinesen believes the large startup costs associated with vertical farming technology require the kind of capital and scale only available in rural areas, or zones already designated for industrial or agricultural use. But he says it’s integral for governments to invest heavily in the sector to help alleviate the type of supermarket shelf shortages that were commonplace at the height of the COVID-19 border backlog.

Despite the enthusiasm shown by some over the industry’s potential, there is skepticism.

“Vertical farming is quite exclusionary in terms of the startup costs and technology costs,” says Sarah Rotz, an assistant professor at York University who studies ecologies of food and land systems. She fears the cost of entry could lead to a monopolization of the global food supply, should vertical farming truly take off.

“When we think about who's investing in farm technology, agricultural technologies, like vertical farming, you've got a lot of people in tech, you've got a lot of large investment firms, a lot of folks from Silicon Valley, you're now seeing Amazon, Google, you know, tech firms. We’re already concerned about corporate concentration in tech, so I see something like heavy investments in high tech agricultural methods and as only advancing that further,” Rotz said.

:It really only serves to reduce demographics, reduce access, and reduce accessibility to food and agricultural production even further. Agricultural tech really only supports highly specialized forms of labor rather than enhancing labor equity. So there's, I think there's a larger political question, is this the direction we want to take as a society, and who are we going to allow to make those decisions and build those investments?”

“I think a country would be scared to rely too much on electricity-dependent agriculture,” said Albert Berry, professor emeritus with the University of Toronto’s economics faculty.

“We have enough hackers going around, that's the sort of consideration that makes me think it's not going to dominate, it's not going to get to 80 per cent (of the farming market), it's much more likely, if all goes well, to get to 40 to 50 per cent,” said Berry. “And then if the world is a very quiet place, nobody's worried about political animosity across countries or the capacity for hackers, it could get higher.”

For Krochmalnek, whose past and future are both rooted in vertical farming, widespread adoption is inevitable. As a teenager, he combined his love of gardening with a burgeoning business mind, planting the seeds for a future he believes can sustain and stabilize our food supply.

“To grow enough calories to feed everyone takes a lot of energy, so it won’t replace outdoor farming. But as we get more sustainable sources of energy, then we can use more and more vertical farms to feed ourselves. It’s a good risk control mechanism for society as well. If we're dependent on imported food, we're at risk if another country decides to not give us a food choice.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Trudeau noncommittal on expanding rebate beyond 'working Canadians'

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau does not appear willing to budge on his plan to send a $250 rebate to 'hardworking Canadians,' despite pressure from the opposition to give the money to seniors and people who are not able to work.

'Mayday!': New details emerge after Boeing plane makes emergency landing at Mirabel airport

New details suggest that there were communication issues between the pilots of a charter flight and the control tower at Montreal's Mirabel airport when a Boeing 737 made an emergency landing on Wednesday.

Cucumbers sold in Ontario, other provinces recalled over possible salmonella contamination

A U.S. company is recalling cucumbers sold in Ontario and other Canadian provinces due to possible salmonella contamination.

Latest updates: Tracking RSV, influenza, COVID-19 in Canada

As the country heads into the worst time of year for respiratory infections, the Canadian respiratory virus surveillance report tracks how prevalent certain viruses are each week and how the trends are changing week to week.

Weekend weather: Parts of Canada could see up to 50 centimetres of snow, wind chills of -40

Winter is less than a month away, but parts of Canada are already projected to see winter-like weather.

W5 Investigates A 'ticking time bomb': Inside Syria's toughest prison holding accused high-ranking ISIS members

In the last of a three-part investigation, W5's Avery Haines was given rare access to a Syrian prison, where thousands of accused high-ranking ISIS members are being held.

Federal government posts $13B deficit in first half of the fiscal year

The Finance Department says the federal deficit was $13 billion between April and September.

Armed men in speedboats make off with women and children when a migrants' dinghy deflates off Libya

Armed men in two speedboats took off with women and children after a rubber dinghy carrying some 112 migrants seeking to cross the Mediterranean Sea started deflating off Libya's coast, a humanitarian aid group said Friday.

Nick Cannon says he's seeking help for narcissistic personality disorder

Nick Cannon has spoken out about his recent diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder, saying 'I need help.'