TORONTO -- Ontario’s reopening plan may be enough to quell a potential fourth wave in the fall thanks to the 21-day intervals between stages and the focus on vaccinations, public health experts say, but not including a framework for opening schools may be problematic.

“There's a lot of positive here in terms of it doesn't look rushed,” Colin Furness, an expert in infectious disease epidemiology from the University of Toronto, said of the reopening plan announced last week.

“We made this huge mistake of just cranking stuff open … and then things would really kick back up so I think we're avoiding that for the first time. That matters.”

Ontario has been under a stay-at-home order since April 8. Under the order, all non-essential retailers closed to in-person shopping, in-person dining was prohibited and gyms and personal care services were shuttered. Residents were told not to leave their place of residence, except for essential reasons such as work, school, trips to a grocery store or pharmacy and for health-care reasons.

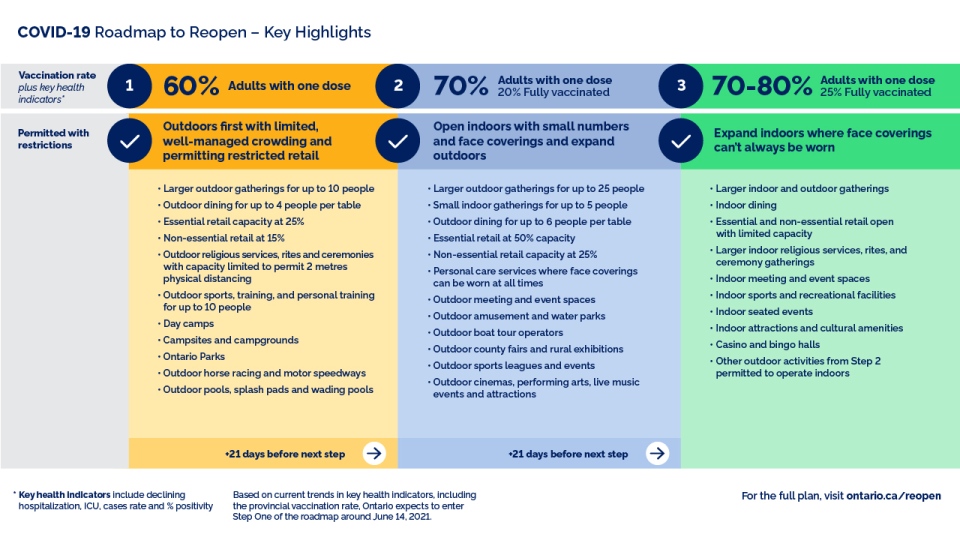

But last Thursday, Premier Doug Ford announced the government had a three-step plan to gradually ease the entire province out of lockdown. The plan prioritizes the opening of outdoor activities and outdoor dining, while allowing non-essential businesses to reopen with strict capacity limits.

Officials predict to move into Step 1 of the plan around June 14 and they say they will wait at least 21 days before opening up any other sectors.

The reopening plan uses vaccination rates as a predominant measure for when the province will move to each step. To move into Step 1, 60 per cent of adults (or just over 8.7 million people) in Ontario need to have received their first dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

According to provincial data released Wednesday morning, about 57.6 per cent of people aged 12 and up have received their first shot. However, by the afternoon, a spokesperson for the Minister of Health said that Ontario had achieved 60 per cent first dose coverage in adults aged 18 and up.

Step 1 could begin two weeks as of today using the government's thresholds.

The reopening plan also takes “key health indicators” such as hospitalizations, intensive care unit capacity, daily case counts and positivity rates into account—however no precise thresholds have been provided.

“It's a good public communication strategy because it makes it clear to people what they need to do, go get vaccinated,” Furness said. “I think that's a super important message.”

“However, the reality is, you can have high vaccination rates and high COVID rates, so you really need to pay attention to them both.”

Dr. Peter Juni, head of Ontario’s science advisory table, says that he believes the government’s June 14 timeline proves they will be taking more than vaccinations into account. By that time, Juni said he expects there to be fewer than 1,000 COVID-19 cases reported daily.

“It's reasonable,” he said when discussing the key indicators. “What we would like to do from my perspective is, before we open any more indoor spaces, we would need to be clearly below 800 cases per day so that we enable the contact tracing and testing system to work again properly without being challenged because of too many cases.”

Dr. Kevin Smith, President and CEO of the University Health Network – a system of hospitals that include Toronto General, Toronto Western and Princess Margaret – says that he hopes to see an ongoing declining trend in hospitalizations and COVID-19 patients in the ICU as the province reopens.

Neither he, nor Juni, could provide any specific numerical thresholds for moving between each step of the reopening plan.

“I think it's going to be one of those day-by-day, week-by-week assessments that really need to carefully monitor the data and perhaps more so than in round one and two and three,” Smith said.

Smith added that on top of the typical COVID-19 data, he hopes that officials take frontline workers into consideration as they are experiencing burn out and will have to continue working long hours in order to make up for the cancellation of elective and scheduled care that was previously put on pause as admission to the ICU soared.

Ontario’s reopening plan also moves the entire province through each step at the same speed—a drastic change from the previous colour-coded framework that takes a region-by-region approach to lockdowns.

The previous framework, which was highly criticized by experts, placed each of Ontario’s 34 public health units into one of five categories based on a series of trends, including positivity rate, weekly incident rates, level of community transmission, hospital and intensive care unit capacity and the disease’s reproductive rate.

Furness said that while he understands the logic behind moving the entire province at the same time in an effort to prevent cross-region travel, it will create some “winners and losers.”

“Other places that don't have very much COVID right now are losers in that because they could be probably opening more safely.”

Both Furness and Juni say that the government prioritizing the reopening of outdoor amenities and outdoor activities is key to its success.

WHAT IS HAPPENING WITH SCHOOLS?

While public health experts say that the reopening plan has a lot of positive aspects, the fact that schools are not mentioned at all is problematic.

“The major criticism is we don't have a plan for schools,” Furness said. “The big problem is we don't understand child transmission, we don't understand the rules of school plan transmission. We're actually really blind.”

Furness said there is divided discourse among parents—some are terrified to send their children to school in-person while others are desperate to send them back.

“The fact of the matter is we haven't done much to ensure that the schools stay safe. We haven't done much to measure the level of danger, so it just represents this neglect—COVID neglect,” Furness added. “We insisted schools were safe without any evidence to do so. Now we're hesitant to open them up again without any evidence to suggest whether that would be a good idea or not.”

Modelling data presented on the same day as the reopening plan suggested that reopening schools on June 2 would likely result in a six to 11 per cent increase in new daily case numbers.

However, the data also showed that such an increase in COVID-19 infection may be "manageable."

Juni suggested that schools could reopen on June 2 ahead of Step 1, along with both organized and unorganized outdoor activity, with the exception of patios. Afterwards, the province would have to wait 21 days before reopening anything else in order to determine the true impact schools have on community transmission.

“I would believe the province wouldn't want to wait for three weeks to open more outdoor activities. So what they actually can do is, they just focus on the outdoor activity simultaneously to schools,” he said, adding that the reopening of schools is the only sector that will not trigger travelling between regions.

At the same time, Juni said that he believes public health units and school boards should be actively involved in the decision and should only reopen in the Greater Toronto Area if they feel it is safe to do so.

On Wednesday, Health Minister Christine Elliott said it is “certainly possible” that the government could take a regional approach to reopening schools, although she provided no further details on what this would look like.

“It is something we are watching very closely and I know (Education) Minister (Stephen) Lecce wants to make sure it is safe for students to return to school at the appropriate time,” she said while acknowledging that the final decision rests with Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health.

Dr. David Williams, meanwhile, told reporters one day earlier that he would like to see children return to the classrooms before the province begins reopening.

“My position has been always, like our public health measures table and our medical officers of health, that feel that schools should be the last to close and the first to open,” Williams told a news conference.

“Ideally, I'd like the schools open before we enter Step 1 of our exit strategy.”

President of the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation Harvey Bischoff told CTV News Toronto that he was “massively disappointed” that schools were not included in the reopening plan.

“Ít’s distressing for a lot of people,” he said.

Bischoff said that a regional reopening to schools in June would “probably be supportable,” depending on further details regarding indicators, timelines and metrics.

“All of these things are uncertain and once again, the government appears to be flying blind, which is pretty dismaying a year into the pandemic,” he said. “I think there are areas in the province where the risks in schools could be sufficiently mitigated that a return makes sense. There are probably areas in the province where that wouldn’t be possible before the end of June.”

Bischoff added the union believes reopening in certain regions with the proper health precautious could be worthwhile, even if it only provides students with two or three weeks of face-to-face interaction before the end of the school year.

Caitlin Clarke, a spokesperson for the Minister of Education, said that the government's priority is to keep students, staff and families safe.

“While the Chief Medical Officer of Health has confirmed that schools have been safe, we will continue to work with him and other medical experts, and education partners, across Ontario on a path forward, as we continue making progress in our battle against COVID-19” she said in a statement.

Speaking on background, a government official said that school closures or moves to in-person learning have never been specifically included in reopening plans.

At the moment, vaccinations are only available to people aged 12 and up, something Furness says could add more complication to school reopening.

“Number one, the (B.1.617) variant is going to be dominant, there's no questioning that,” he said. “Number two, we're still going to have millions of people not yet vaccinated. And those two facts together suggest that we could be facing quite a mess in the fall.”

WHAT’S THE RISK OF A FOURTH WAVE?

There is no doubt going into Ontario’s third reopening plan since the beginning of the pandemic that people are tired of lockdowns and do not want another one to take place.

Since the stay-at-home order was issued, Ontario’s daily case counts and hospitalizations have declined significantly. On Wednesday, health officials reported 1,096 new COVID-19 cases. On April 8, when the provincewide stay-at-home order went into effect, that number was 3,295.

Juni said he “strongly believes” that if Ontario’s lockdown exit is measured and continues to prioritize the reopening of outdoor spaces, while giving three weeks between each step, it should prevent a fourth wave from occurring in the fall.

“From a pandemic cultural perspective. I'm actually convinced that this will work out,” he said. “I would be much more concerned if we started to go back to this really dramatic error that was made in February (and) March ,you know when big box stores started to open.”

“If we only use outdoor space smartly and continue to vaccinate and then say okay if we do just one thing right, that's opening schools, then we can avoid any challenges there.”

Furness added that he doesn’t think schools “are going to be the fourth wave,” but rather will be a “participant or a risk factor.”

He added that “the fourth wave is definitely on the menu” if the B.1.617 variant continues to spread and vaccinations don’t increase.

“The idea of a fourth wave, yeah it's entirely possible. Again, it is that the pieces are there, but it’s not in my estimation. It's not t a for sure thing.”