TORONTO -- Paulette Walker’s life could have gone in either direction. She could have ended up in jail, but instead she found treatment – and a whole new life thanks to the Toronto Drug Treatment Court.

Walker says she didn’t realize it at the time, but childhood trauma set her on a self-destructive path.

She had family who loved her, but she says there was also “sexual and physical abuse, verbal abuse, a sense of loss, abandonment.”

She became a successful makeup artist in her 20s but things fell apart for her one night in 1985. She went partying after wrapping up work on a televised awards show and on the eve of starting a new job with a major Canadian women’s magazine.

“I ended up in a crack house for two weeks,” she said.

She says crack cocaine crept into her life gradually. Once in a while turned into once a month, once a week and then more. She lost her job, lost her home and eventually, after years of struggling, she was arrested in a drug bust and brought before Judge Paul Bentley.

“He says “Do you want to stop using drugs?” she recalled. “And in that moment, I said ‘Yeah I do but I don’t know how.’”

In 1998, Bentley had introduced the Toronto Drug Treatment Court, which diverts non-violent people from the criminal justice system and puts them into treatment for problematic substance abuse. It’s a model that’s since been adopted in several Canadian cities.

“In those days we called it addiction,” said Justice Mary Hogan, who took over the program after Judge Bentley passed away.

“I think our court has tried to evolve with what we know now about problematic substance abuse as opposed to what we knew in 1998” says Hogan. “I would say we’ve become more harm-reduction focused.”

She calls the program a unique collaboration between the criminal justice system and the health-care system. Clients spend a minimum of a year in the program with counselling and treatment, working with CAMH therapists, and the legal team at Old City Hall courts tries to build a supportive and friendly relationship with clients.

Success viewed in many ways, but reduction in substance use or dependence is typical.

“They’ve achieved a sense of dignity, self-worth and they’ve been able to reintegrate into the community. And they often have re-established their ties with family,” Hogan said.

Hogan says the program has been hit hard by the pandemic. It’s not at the top of the list for funding to convert to online services. Restrictions on the number of people allowed to congregate have hampered the way treatment decisions are made and many clients lack access to things like Zoom.

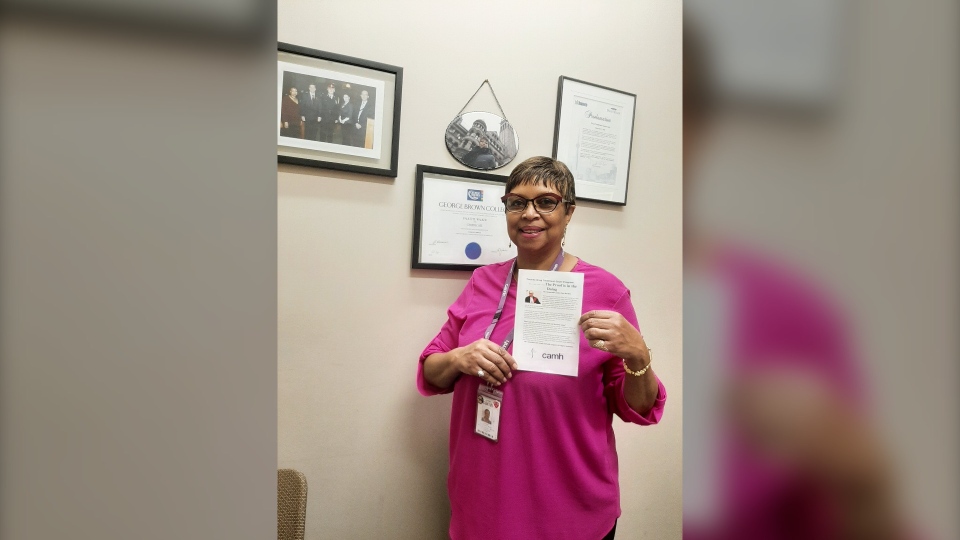

Walker successfully completed the program years ago and went on to become a chef, and later a peer counsellor for CAMH. She was invited by Bentley to speak at the United Nations and now she works at CAMH as a counsellor for the Toronto Drug Treatment Court.

“I never thought in a million years that my life would change as much as it has,” she said, while thanking Bentley, who she keeps a photo of on her wall as a reminder and an inspiration.

“He saved my life and gave me a fresh start and a sense of community.”