Smarter. Stronger. Faster.

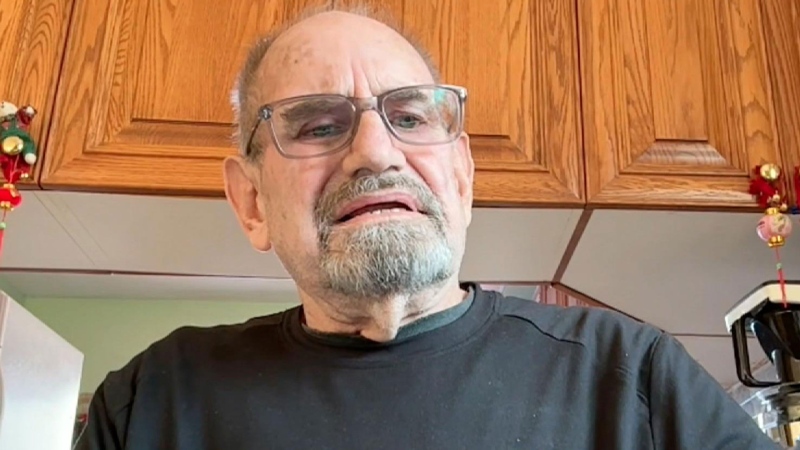

That's the catchphrase for the indoor cycling studio that Peter Oyler co-owns. The words are posted in huge letters on the white wall behind him as he pedals away on a stationary bike one recent afternoon at the Toronto facility.

But the mission statement for Oyler's business could also be the motto for another, very personal pursuit.

On Wednesday the 39-year-old from Toronto will set out from California in the gruelling Race Across America for a second time.

The route from Oceanside to Annapolis, Md., is more than 4,800 kilometres, taking riders through 14 states and climbing more than 30,000 metres. Just making it to the finish line is considered a huge accomplishment in the world of endurance sports.

Oyler has already reached the finish once, a feat that took just over 11 days in 2007. It was good enough for an eighth-place finish out of 24 male solo riders.

But it wasn't good enough for Oyler and this year, he's looking to shave a whopping two days off his time. Impossible? Some may think so. But Oyler says it can be done because he's spent the past two years becoming smarter, stronger and faster.

"I feel better prepared than I did in 2007 for sure," Oyler says after finishing a training session with one of his clients. "This time around there's been more science behind my training.

"I'm feeling a lot more confident in my strength going into the race... I can do things now that I couldn't do when I was 20 years old."

Oyler will be among two Canadians in the event. Tony O'Keeffe of Kingston, Ont., a finisher in 2006, is also entered. But the man to beat will be four-time winner Jure Robic, a special forces soldier in the Slovenian army who won the solo category in 2008 in eight days 23 hours 33 minutes.

"He's extremely strong," says Oyler. "Every single time that he's won the race, he goes out as hard as he can and if anybody can stay with him that's great but eventually he cracks them and it's a race for second place."

Unlike cycling's most famous competition - the 3,500-kilometre Tour de France - the Race Across America is not broken into stages. The more hours riders can put in without stopping to rest, the better their time will be. Solo riders like Oyler - there is also a team category - average 400 to 500 kilometres a day and will stay awake for hours on end.

"It's tough to find a more difficult race in the world for a solo effort than this," Oyler says as he sits at a small table piled with towels and sips a protein drink from a plastic bottle. "It's pretty special to be able to do it."

Oyler says doing it costs upwards of $50,000, money that's mostly been provided by his stable of sponsors. He's also riding in support of Kids Help Phone again this year.

The Race Across America, known as RAAM, isn't a challenge for the novice cyclist.

At the peak of his training, the six-foot, 167-pound Oyler was logging as many as 35 hours a week on his bike, either on the roads of southern Ontario or the trainer at his studio, WattsUp Cycling. The facility, which is tucked away in an industrial park in Toronto's east end, specializes in a high-tech, power-based training program that Oyler says has helped him improve his fitness.

In fact, during the winter, there were a few weeks when he was barely able to get outside due to slick roads and bad weather. So he logged the majority of his training hours indoors at the studio.

Oyler is lucky because he can combine his job with training. If he's teaching a class at the studio or working with a client, he is still logging time on his bike. His schedule is also flexible enough that he can teach a morning class, then spend the afternoon riding outdoors before returning to teach again in the evening.

His training rides have varied in length from an hour or two to longer stints of perhaps 12 or 14 hours at a time. But now that the race is almost here, he's in taper mode and his really long rides are finished.

"It's a passion," says Oyler, a soft-spoken former teacher with close-cropped salt and pepper hair. "Otherwise I wouldn't do it. It's a lot of lonely hours."

The good news is he won't be completely alone for his journey across America. He'll have an eight-man crew along for the ride, taking care of pretty much all his needs. With five returning members from the 2007 crew, Oyler is convinced the experience will lead to a smarter logistical approach to the race.

In 2007, 15-minute pit stops often turned into 45-minute breaks and Oyler says keeping to a more rigid schedule will do wonders for shaving off hours.

"If you did the math on how many times that occurred, it's almost a complete day," he says of the undisciplined stops.

Maintaining the schedule will be one of the many things crew chief Joel Fraser will be responsible for. A police officer in Peel Region, Fraser has known Oyler for about 10 years. Oyler's father Peter Sr., who lost 40 pounds so he could be in better shape for the race, is also a member of the crew.

Things can get tense on the road but they're a closeknit bunch who can say pretty much anything to one another without any hard feelings.

"It's not personal," says Fraser. "We have a really good group."

The crew will cover the distance with Oyler only they'll be in support vehicles and doing everything from driving, to navigating, to getting Oyler the Big Mac he craves to convincing him he needs a break because he's hallucinating due to sleep deprivation.

Balancing sleep with riding is among the biggest challenges of the entire race. Oyler recalls that in 2007 he was so weary due to lack of sleep, he tried to get into the back of a transport truck on the side of the road. Another time, in Kansas, he found himself weaving along the road.

"Funny things do happen," says Oyler. "You say things and have no clue what you're saying."

That's when Fraser and his crew need to step in and put Oyler to bed. That could mean wheeling into a roadside motel for a few hours so everyone can rest or just lying him down on the side of the road with a blanket for an hour or so. Sometimes, that's all it takes for him to recharge.

Oyler, who has completed 13 Ironman triathlons, is doing all he can to make sure he's prepared for anything. He has tried staying up for extended periods of time - one stint lasted some 40 hours and he admits he felt awful by the end of it. In recent weeks, he has been sleeping in a special altitude tent that he set up in his living room.

He acknowledges all this meticulous preparation has put a bit of strain on his personal relationships. His wife, Kathy Yakimik, a nurse in Toronto, would worry about him while he was on those marathon training rides all alone.

"She'll be happy when it's over," Oyler says with a laugh, adding that Yakimik will be at the finish line to meet him in late June.

Oyler has also done night rides and tried to get out in all kinds of weather, just to make sure there are no surprises. He'll pack for all the conditions he'll encounter along the way, from sweltering desert to chilly mountains.

But he knows there will be times when he wants to give up. That's where Fraser and his crew come in. They'll be there to provide as much motivation as possible, whether it's lifting his spirits with a few bad jokes or leaning out the car window and reading him inspirational email messages from home.

"He knows what he needs to do," says Fraser. "There are going to be times when he needs different pushes and shoves."

Food is another huge motivator. He expects he'll drop at least five pounds by the time he finishes so getting enough calories is key, but he doesn't get too caught up in trying to stick to a strict diet during the ride. He pretty much eats whatever he feels like having and it's up to the crew to find it for him.

"The bottom line is it's their job to see to it that if I want a cheeseburger, they find a cheeseburger," he says. "That's what's going to drive me to keep going forward, the calories and desire to chew something."

During training, high carb foods that are easy on his stomach dominate his daily diet. Prior to one of those long, gruelling training rides, he would stuff himself with as many as 15 fluffy pancakes the night before. Pasta is also a staple as are sports drinks and gels.

But after hours upon hours of riding, there's one thing he looks forward to more than anything else - a cup of coffee from Tim Hortons. He doesn't even treat himself to a Tim Bit.

"A 12-hour ride and then get a coffee," he says. "I'm pretty simple."

There will be no Tim Hortons at the finish line in Annapolis, of course. But meeting his goal of nearly 5,000 kilometres in nine days would be a pretty statisfying reward.