TORONTO -- An investigation aimed at pinpointing the source of a lingering bacterial outbreak in a Toronto hospital turned up an unlikely suspect.

The sinks did it.

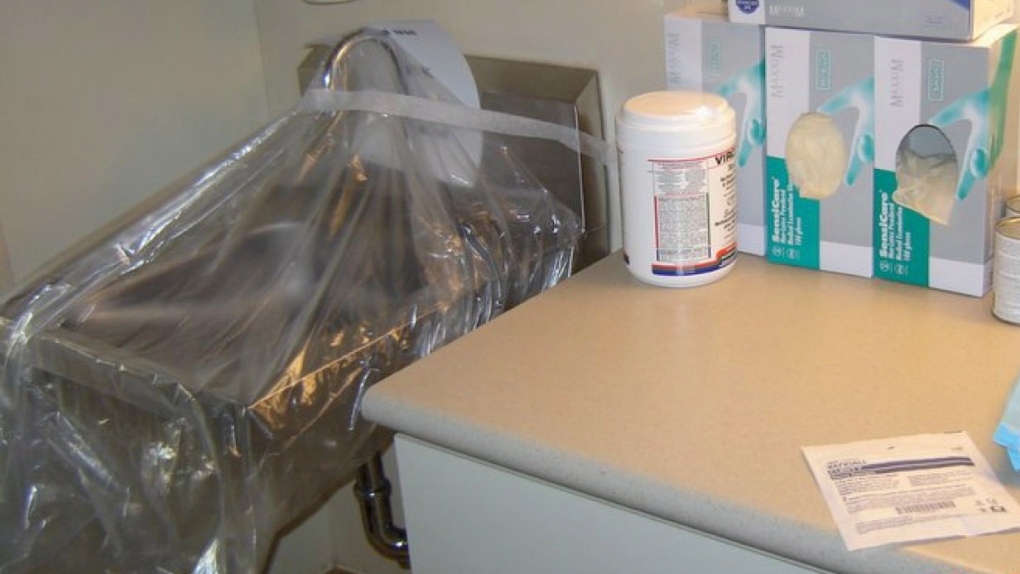

State-of-the-art handwashing sinks installed in the intensive care unit and some patient rooms in Toronto's Mount Sinai Hospital actually became the reservoir of a pesky drug-resistant bug that infected or colonized 66 patients from the fall of 2006 to the spring of 2011.

Researchers from the hospital have reported the finding of their investigation in the August issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The outbreak involved Klebsiella oxytoca, a bacterium that normally lives in the human gut. It typically causes urinary tract infections, but can also trigger bacteremia -- infection in the blood.

It's not uncommon. But when infection control staff at Mount Sinai noticed in the fall of 2006 that they had three or four cases caused by a similar strain, they set out to figure out what the source was in a bid to shut down what appeared to be in-hospital transmission.

Dr. Allison McGeer, Mount Sinai's head of infection control and senior author of the study, says hospitals know that as a rule these bacteria spread from a patient who is carrying them to other patients.

Find the colonized patient -- a person carrying Klebsiella oxytoca but not sickened by them -- and make sure he or she is treated in isolation, and you can prevent transmission.

That's the way it's supposed to work. And using anal swabs, the hospital staff did locate people carrying the bacteria. But despite taking the appropriate measures, the bug continued to spread.

When ICU patients became infected even though there were no Klebsiella oxytoca carriers in the ICU, it became clear there had to be a non-human source. Then began a process of elimination.

"If your reservoir is patients, then it should not happen that new people acquire it when there isn't a colonized patient there," says McGeer. "Eventually what is left must be the truth."

It's not unheard of that sinks can be a source of infection. In fact, shortly before Mount Sinai's fight with Klebsiella oxytoca began, a neighbouring hospital, the University Health Network, battled a more serious 16-month outbreak in its transplant unit.

That outbreak, caused by the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, resulted in 36 patients becoming either colonized or infected. And 17 of them died. (There were no deaths in the Mount Sinai outbreak.)

Pseudomonas are commonly found in drains. And the sinks in the transplant unit had shallow basins and high, gooseneck spouts that flowed directly into the drain below. Because of that design, the pressure from the spout splashed water out of the drain, spraying nearby surfaces with bacteria-laced droplets.

Dr. Michael Gardam is McGeer's counterpart at the University Health Network. He says since his hospital's outbreak, he believes getting staff to clean their hands with alcohol gel instead of soap and water is the better way to go in many settings.

"It is the ultimate irony," he says.

"We've pushed so hard to get these sinks in every room. That's the new building standard... And it has to be in a place where you can easily access it, which is at the point of care, so it's really quite close to the patient."

"Have we in doing that unwittingly created a system whereby you've got a little beaker of drug resistant organisms right next to the person that you're trying to protect? That's something that I would not have thought of until I went through this with our own problem."

In the Mount Sinai outbreak, McGeer's team believes sinks became contaminated when staff used them to dispose of body fluids. Not urine, she says, but perhaps fluid from chest tubes or half-used IV bags.

"There's a lot of fluid that needs to be disposed of from ICU patients from a whole variety of sources," she says.

"When you have to empty chest tubes, when you have assorted drainages, if you need to rinse things off, there's a tendency to use the sink."

When infection control told cleaners to scrub the sinks three times a day, transmission slowed. But that schedule is hard to maintain and when it slipped, the bacteria would start to spread again.

McGeer says in the end some relatively simple changes to the mechanics of the sinks seem to have solved the problem.

Drains are now covered by screens with smaller holes, to minimize the potential for back splash. The overflow drains were blocked and traps were moved further back from the basin.

"It was an interesting discovery," McGeer says of finding that sinks were the source of the problem. The tone of her voice casts the word "interesting" in italics.

McGeer suggests there is a lesson to be learned about hospital sinks here.

"They are a potential risk. And the fact that the sinks designed the way we had them were not supposed to do this does not mean they can't."