'Project Litoria': How Toronto police charged a now-acquitted mother in the death of her disabled daughter

Amanda Ali apologized to the court, stopping to collect herself before reading the eulogy she’d written and delivered at her younger sister’s funeral more than 10 years prior.

“From Cynara’s 16 years, we have beautiful memories that we will cherish forever,” Amanda, now in her mid-30s, read from the witness box at her mother’s retrial at Toronto’s Superior Court of Justice in December.

- Download our app to get local alerts on your device

- Get the latest local updates right to your inbox

Her father, Allan Ali, and sister Carissa Ali stared on as Amanda testified in defence of her mother for a second time in her life.

“We will remember both her laughter and her tears. She has been an inspiration for us,’ Amanda read.

Cynara died in February 2011 at the age of 16. After more than a year of investigation by the Toronto Police Service (TPS), her mother, Cindy Ali, was charged with first-degree murder.

Cindy has always maintained, to police and in court, that Cynara died following a home invasion at the family’s Scarborough, Ont. townhouse.

When the case went to trial, nearly five years after Cynara died, the Crown alleged Cindy smothered her daughter, who lived with cerebral palsy and epilepsy, after the girl had become too heavy a burden to bear. According to the prosecution’s theory, Cindy staged her home, either before or after the alleged murder, to appear as if a break-in had occurred.

A jury deliberated for about 10 hours before convicting Cindy of first-degree murder. She was handed a life sentence with no chance of parole. In 2021, that conviction was quashed and Cindy was granted another trial.

For more than a decade now, Cindy's family — Allan and Amanda, and her twin daughters Carissa and Clarissa — alongside the dozens of fellow congregants of the family's church, present near-daily at both trials, have maintained her innocence, describing the mother as dedicated and Cynara as a cherished member of the family.

"The system needed to give some credit to Cynara’s nearest and dearest here," Cindy's lawyer, James Lockyer, said in the closing arguments of last year's retrial.

"It's a common feature of domestic homicide wrongful convictions that the family never believed it was a murder. In this case, they believe Cindy would never, and while it doesn't prove she didn't do it, it's a factor that helps prove it," he said.

At last year’s retrial, Lockyer and cocounsel Jessica Zita suggested police focused too narrowly on the Ali family and did the bare minimum to investigate Cindy’s account of her daughter’s death. The 13-month investigation turned up nothing of significance, Lockyer argued, but "still hurts the family to think about."

Asked by Lockyer when, during the year her family spent under investigation by Toronto police, she had time to process and grieve Cynara’s death, Amanda said through sobs from the witness stand, “I didn’t.”

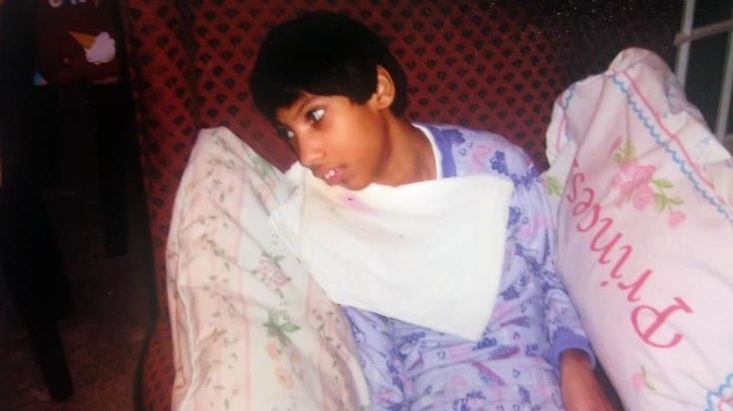

Cynara Ali with her sisters, celebrating a birthday in a Toronto Superior Court of Justice exhibit from Cindy Ali's 2016 trial.

Cynara Ali with her sisters, celebrating a birthday in a Toronto Superior Court of Justice exhibit from Cindy Ali's 2016 trial.

On Jan. 19, nearly 13 years after Cynara died, Superior Court Justice Jane Kelly acquitted Ali of the first-degree murder charge. Kelly also found her not guilty of the included offences of second-degree murder and manslaughter. While the judge noted she was left in a state of uncertainty about the events that took place on the morning of Feb. 19, 2011, she found the Crown had failed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Cindy had committed the offences.

When reached for comment in the aftermath of the decision, the Toronto Police Service said it conducted a “full and thorough investigation” into Cynara’s death.

“As is the right of any individual, an appeal of the conviction was applied for and granted, and today the presiding Justice found Ms. Ali not guilty," a spokesperson for the service said in the statement. "The criminal justice system worked as it was designed to,”

When read the statement, Zita put forth no argument to claims of a thorough investigation.

“Police thoroughly investigated Cindy, for sure," she said in an interview with CTV News Toronto last week. "Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for Cindy’s home invasion story."

Past its initial statement, the Toronto Police Service has denied answering additional questions about the investigation. Frank Skubic, the now-retired lead detective on the case, did not respond to CTV News' requests for an interview.

The following breakdown of the police investigation into Cynara's death, dubbed by police 'Project Litoria,' is drawn from an Admission of Fact, presented as evidence in the final days of the retrial.

'Dont bulls--t me'

On the morning of Feb. 19, 2011, Cindy and Cynara were home alone at the family’s Scarborough townhouse when, according to Cindy, two men pushed their way into the home looking for “a package.”

One of the men guided Cindy through the house, she testified, while the other remained in the living room with Cynara. When Cindy returned to the living room, she told the court she saw her daughter lying lifeless on the couch while the other man stood beside the girl, holding a pillow.

According to her testimony, the two men then claimed they’d gotten the wrong house before fleeing.

“I grabbed the phone. I was sitting right next to Cynara and when I called 9-1-1, I passed out,” Cindy said from the witness box in November.

Cindy Ali told court she saw one of the home invaders standing near the couch with the pillow on the left in his hands. The Crown argued that Ali used that pillow to smother her daughter after staging a home invasion. (Court exhibit)

Cindy Ali told court she saw one of the home invaders standing near the couch with the pillow on the left in his hands. The Crown argued that Ali used that pillow to smother her daughter after staging a home invasion. (Court exhibit)

Toronto firefighter Semahj Bujokas was the first person to arrive at the Ali residence that morning.

From the outset, Bujokas cast suspicion upon Cindy’s account of the home invasion.

In both trials, Bujokas testified that he hadn’t observed footprints leading up to the home on the day of the call, despite flurries falling earlier that morning. Had two men broken into the home, Bujokas told the jury, and later the judge, he would have expected a fresh set of prints.

“There are no footprints, don’t bulls--t me,” he can be heard telling Cindy in the 9-1-1 call, played to the court. He briefly assessed Cindy for injuries before kicking her and telling her to “get up,” according to both his and Cindy’s testimonies. Cindy told the court her body had gone “numb" at the time. “I had no feelings anymore,” she said.

Bujokas then noticed Cynara lying on the couch. He recorded that she had no pulse and wasn’t breathing. After a short time spent administering CPR on the girl, the firefighter revived her vital signs, and she was taken to hospital.

During Bujokas’ time in the witness box in October, Lockyer suggested the firefighter had developed a “vested interest” in the case, after reviving Cynara and testifying repeatedly over the last 10 years. The lawyer pointed to a series of texts sent in October 2021 from the firefighter’s phone to a documentarian working on a film about the case.

One of the texts read, “If it's a retrial, I will make sure every question I want is asked. There will be no doubt, no question, and no chance, the outcome will be the exact same.”

When reached for comment, Toronto Fire declined to provide comment or answer questions past what is contained on the public record.

At midnight on Feb. 21, Cynara was pronounced dead.

Her cause of death remains unclear. While “cardiac arrest due to lack of oxygen caused by a brain injury” is listed on her autopsy report, Dr. Charis Kepron, with Ontario’s Forensic Pathology Service, later testified that the term was “a fancy way of saying, ‘We don’t know.’”

Back at the hospital, in the hours before Cynara’s death, Cindy was kept away from her daughter and the rest of her family, an officer standing guard at the door of the hospital room.

Cynara Ali can be seen at a family outing. (Superior Court of Justice Exhibit)

Cynara Ali can be seen at a family outing. (Superior Court of Justice Exhibit)

'Project Litoria' begins

The initial search and forensics sweep of the Ali home found no physical evidence of the two men. However, during proceedings years later, investigators admitted they failed to print certain areas, including some cupboard handles Cindy said the men touched and a set of knives she said she threw at the alleged intruders.

In the direct aftermath of Cynara's death, police interviewed almost all of the Ali extended family, along with their friends, neighbours, and fellow congregants. Surveillance of Allan, his aunts, uncles, and cousins, Cindy’s sister and her children, and Amanda and her then-boyfriend was also initiated. During this time, police were granted a production order for Cynara’s long-term care records and the family’s immigration file.

From there, the Admission of Fact makes no mention of any efforts made by police to search for two intruders. Instead, the investigation that followed focused almost exclusively on the Alis.

Police canvas the Ali's Scarborough townhouse complex in the aftermath of Cynara Ali's death, in March 2011 (CTV News)

Police canvas the Ali's Scarborough townhouse complex in the aftermath of Cynara Ali's death, in March 2011 (CTV News)

In the time between the 9-1-1 call and when Cynara was taken off life support, both Allan and Cindy gave lengthy interviews to police. Neither had legal counsel present. While both were told it was “important” to give their statements while the investigation was still in its early stages, they were also informed they were not required to do so. Amanda, alongside twins Carissa and Clarissa, was also called into 42 Division to give separate statements, just hours after their sister's death.

By day’s end on Feb. 21, less than a full day after Cynara took her last breath, Toronto police had been granted a search warrant that listed first-degree murder as the suspected offence.

Cynara Ali can be seen above sitting in front of a birthday cake. (Exhibit: Superior Court of Justice)

Cynara Ali can be seen above sitting in front of a birthday cake. (Exhibit: Superior Court of Justice)

One of the first people detectives interviewed was a neighbour of the Alis, Sureerat Chariyadom, who told police she’d seen two men in the complex parking garage that matched the description given by Cindy and at roughly the same time Cindy had called 9-1-1. After leaving the parking garage, Chariyadom told police she then made a bank transaction at a nearby ATM.

That bank transaction – one of the only pieces of information in the case that stood to corroborate Cindy’s home invasion account – was never confirmed by police, investigators admitted in the retrial. It remained unconfirmed until Lockyer took on Cindy's case and checked the receipt himself, finding that the timing fit with that of Cindy's 9-1-1 call.

Just over a week after Cynara’s death, on March 1, police called another connection of the Ali’s – Jessica Arthur, a volunteer at the family’s church.

Detectives asked Arthur a number of questions, including whether she had ever viewed Cindy as “at the end of her rope.”

“Do you know who Robert Latimer is?” an officer asked Arthur, she told the court from the stand in December. Latimer, a Saskatchewan farmer, was convicted in 1993 of killing his daughter, who lived with cerebral palsy, in an admitted mercy killing that captured international attention.

“I told him no,” Arthur said. Detectives then explained Latimer's story to Arthur before asking her if she believed Cindy could have engaged in a “mercy killing,” to which she replied, ”Absolutely not.”

The next two weeks saw detectives interview at least a dozen more individuals connected to the Ali family. The investigation proceeded as such until March 16 when Allan arrived at 42 Division.

He was there, he told officers, to turn in a letter he’d just found in his mailbox.

A letter of unknown origin

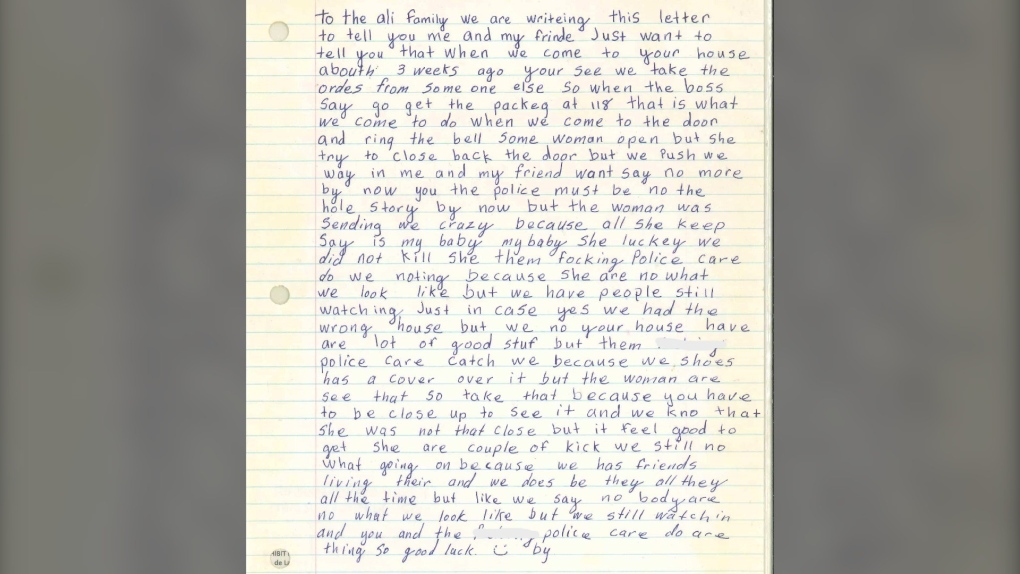

The letter, penned in the voice of the alleged intruders, said the two men had carried out the break-in under the instruction of a "boss" but "got the wrong house."

“To the Ali family, me and my friend just want to tell you when we come into your house about 3 weeks ago you see we take the orders from someone else,” it begins.

“Them focking police can’t catch us because we shoes has a cover over it," another excerpt reads, referencing a lack of footprints left at the scene on the morning of the incident— information only Cindy, the intruders, or first responders would have been privy to at the time.

A letter delivered to the Ali home and taken to TPS' 42 Division about a month after Cynara's death can be seen above. To this day, its origins and author are unknown. (Superior Court of Justice Exhibit)

A letter delivered to the Ali home and taken to TPS' 42 Division about a month after Cynara's death can be seen above. To this day, its origins and author are unknown. (Superior Court of Justice Exhibit)

In both trials, the Crown alleged Cindy had written the letter to throw investigators off, disguising her handwriting to evade identification. Lockyer, on the other hand, argued Justice Kelly should not consider the letter in last year's proceedings. He argued it could not be conclusively tied to Cindy and may have been written either by police or anyone trying to divert attention from the family.

"There is no evidentiary linkage between the letter to Cindy and, if I'm right, it cannot at all carry any weight in this trial," Lockyer argued in his final address to Kelly. "Cindy, of course, can not be held responsible for a third-party action, whether it was the action of a police officer or someone trying to help her."

Two days after Allan turned in the document, each of the Alis submitted handwriting samples, fingerprints, and DNA samples. To this day, the letter’s author and origins are unknown.

In the month that followed, detectives conducted at least two additional interviews and brought Chariyadom into 42 Division for a photo lineup. Then, efforts dropped off.

“The investigation slowed down after May,” Zita said. “Come November, it picked back up again at full speed.”

A simulated raffle

Surveillance of the Ali family didn’t resume for another eight months, until November 2011. Then, detectives were granted judicial authorization to intercept the communications of more than 20 people in or connected to the Ali family, to track the family’s mobile devices and vehicles, and to install probes in both the living room and basement of the townhouse.

Installing the devices would require discreet access to the Ali's home and vehicles. To do this, police first disabled Allan’s car keys “to facilitate the installation of a car probe,” according to the court document.

He spoke of the ordeal, which took place on Dec. 18, 2011, from the witness stand.

“I went to start my van, but it wasn’t working, so I called a tow truck,” Allan told the court, most recently in mid-November.

After discovering the malfunction, Allan said he was approached by a Toronto police officer who asked him what was wrong. When Allan explained his situation, the officer told him there’d been a number of car thefts in the area as of late. According to the Admission of Facts, the detective's intention was to mitigate any suspicion spurred by the car’s failure.

The Burrows Hall Boulevard townhouse complex can be seen above on Feb. 19, 2011. (CTV News Toronto)

The Burrows Hall Boulevard townhouse complex can be seen above on Feb. 19, 2011. (CTV News Toronto)

Two days later, Carissa received a call informing her she won an all-expenses-paid trip to Niagara Falls. She could bring as many family members as she'd like, she was told.

Speaking from the stand in mid-November, Allan said he was initially hesitant to allow Carissa to accept the offer.

“I get a call from Carissa and she says, ‘Hey dad, I won a prize,’ and I said, ‘“Oh yeah? And who provided that prize?’” he said from the witness box in mid-November.

Allan was then connected with someone who identified themselves as 'Lauren' and claimed to work at Scarborough Town Centre. “I was told, 'It’s a real prize and they were lucky enough to win,” he said.

So, he agreed. “It was [the twins’] 16th birthday, so we accepted the prize," he said.

It wasn’t until nearly a decade later, in the process of filming the documentary, that the producer first informed the Alis of the true nature of the interaction – that the mall employee had in fact been a plainclothes police officer and there’d been no real contest.

In early January, nearly a dozen of the Ali family members embarked on the trip to Niagara while police took the opportunity to enter their home and install probes

"It was one of the first times we ventured out on an occasion without Cynara,” Allan told the court.

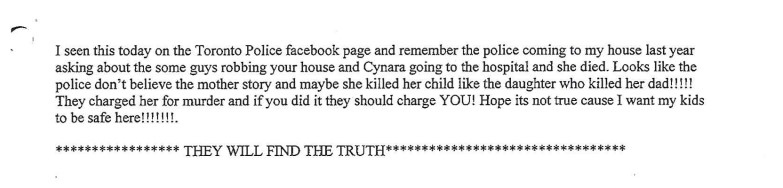

A month later, the Alis found a second letter in their mailbox — this time, crafted and placed by police. The document contained print-outs of Facebook posts made by Toronto police that featured both comments disparaging Cindy and questioning police investigative capabilities. The purpose of the plant, according to the Admission of Facts, was to stimulate conversation between the Alis and others that could then be intercepted.

A portion of a letter left at the Ali residence in 2012 can be seen above. (Superior Court of Justice Exhibit)

A portion of a letter left at the Ali residence in 2012 can be seen above. (Superior Court of Justice Exhibit)

On the morning of March 8, 2012, Skubic arrived at the Ali family house with a warrant for Cindy's arrest. Police first charged her with manslaughter and six other offences, including failing to provide the necessities of life, attempting to obstruct justice, and two counts of fabricating evidence. Eight months later, the charge was upgraded to first-degree murder by the Crown, citing reason to believe Cindy had lied about the home invasion.

In his final arguments, Lockyer said that the lack of evidence turned up by the investigation suggested an “absence of evidence” in the case.

“Despite this extraordinary investigation and this extreme focus on the Ali family, we have heard nothing about the investigation at this trial because there's nothing to tell you," he said.

Lawyer James Lockyer speaks to the media following the acquittal of Toronto mother Cindy Ali on Jan. 19, 2024. (Abby O'Brien)

Lawyer James Lockyer speaks to the media following the acquittal of Toronto mother Cindy Ali on Jan. 19, 2024. (Abby O'Brien)

Case highlights issues of trust in policing: lawyer

In her interview, Zita called the investigation "all-encompassing" and said it has forever left a mark on the family.

“I’ve just never seen one person, or a family, especially with no criminal record, to be investigated like that,” she said. “They’ve never had a normal amount of space nor peace to grapple with the loss of Cynara."

Theresa Donkor, a criminal defence lawyer in Toronto with no connection to the Ali case, told CTV News Toronto that the events serve as an “unfortunate example” of distrust between racialized communities and police.

“There’s already data that shows that racialized communities have little to no confidence in policing and this case is one of many examples that explains why,” she said. “If the system is working properly, you’re supposed to be treated as innocent until proven guilty, but, based on the evidence in this case, in many ways, Ms. Ali was treated as guilty until proven otherwise.

Zita echoed similar sentiments. “I think all women or anyone who is part of a visible minority or is vulnerable or doesn't fit a certain preconception should feel a sense of trepidation after this case," she said. “Cindy's a very prominent example, but there are tons of others – often, women are just not seen by law enforcement as honest or credible."

Cindy Ali can be seen above. The Toronto mother was formerly convicted of first-degree murder in the 2011 death of her daughter, Cynara, before being acquitted by a judge Friday. (Abby O'Brien)

Cindy Ali can be seen above. The Toronto mother was formerly convicted of first-degree murder in the 2011 death of her daughter, Cynara, before being acquitted by a judge Friday. (Abby O'Brien)

When asked in the moments after the acquittal, how she would begin to rebuild trust in her public institutions, Cindy, standing with her family and friends by her side, said it would take time.

“It’s been a really tough road. Now, it’s time for my family to start healing.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

BREAKING Poilievre to submit letter to Governor General asking to recall House for confidence vote

Conservative Party Leader Pierre Poilievre announced that he will submit a letter to the Governor General asking to recall the House for a confidence vote.

'I understand there's going to be a short runway,' new minister says after Trudeau shuffles cabinet

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau added eight Liberal MPs to his front bench and reassigned four ministers in a cabinet shuffle in Ottawa on Friday, but as soon as they were sworn-in, they faced questions about the political future of their government, and their leader.

Judge sentences Quebecer convicted of triple murder who shows 'no remorse'

A Quebecer convicted in a triple murder on Montreal's South Shore has been sentenced to life in prison without chance of parole for 20 years in the second-degree death of Synthia Bussieres.

BREAKING Fake nurse Brigitte Cleroux sentenced to 7 years in prison

A woman who illegally treated nearly 1,000 patients in British Columbia while impersonating a nurse has been sentenced to seven years in prison.

Poilievre to Trump: 'Canada will never be the 51st state'

Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre is responding to U.S. president-elect Donald Trump’s ongoing suggestions that Canada become the 51st state, saying it will 'never happen.'

Toronto officials warn of possible measles exposure at Pearson airport

Toronto Public Health (TPH) is advising of another possible measles exposure at Canada’s largest airport.

Party City closing in U.S., Canadian stores remain 'open for business'

The impending closure of all Party City locations in the United States will not extend into Canada.

BREAKING At least one dead and 50 injured after a car drove into a German Christmas market, official says

A car plowed into a busy outdoor Christmas market in the eastern German city of Magdeburg on Friday, leaving at least one person dead and injuring at least 50 others in what authorities suspect was an attack.

Guelph man facing assault charge after police say he spat in roommate's face during disagreement over cat

A fight between roommates has led to an assault charge for a Guelph man.