TORONTO - Ontario may have new rules before the end of the year to restrict how the highly addictive painkiller OxyContin is prescribed and dispensed, as well as other narcotics and controlled substances, government officials said.

The abuse of OxyContin is a "serious problem" and an urgent issue that's destroying lives across the province, Health Minister Deb Matthews said Thursday.

"This is something I'd like to move on as quickly as we possibly can," said Matthews.

"I've seen firsthand the impact that addiction to OxyContin can have."

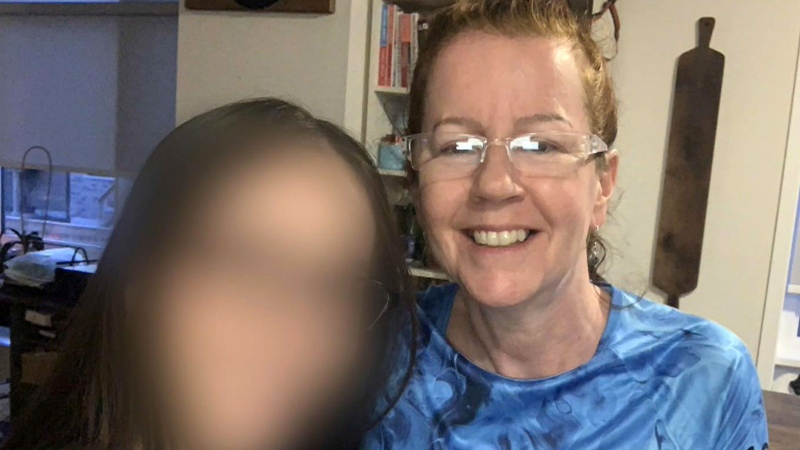

During a drive-along with police in London, Ont., Matthews said she met a mom who had everything going for her, including her own business.

"She was put on OxyContin because of an injury to her back," Matthews said.

"She subsequently became addicted, lost her family, lost her business and was working the streets in London. That kind of got my attention, I'll be honest with you."

One of the big concerns is that public dollars are being used to pay for the pills, which are getting out on the streets and fuelling addictions that are "truly devastating," she said.

Shaken by what she'd seen in London and elsewhere, Matthews brought the matter to assistant deputy minister Helen Stevenson, who is now looking at new measures to curtail the abuse of OxyContin -- dubbed "hillbilly heroin" by some -- and other opioid pain pills.

Stevenson, who also oversees Ontario's public drug programs, said the Health Ministry will impose new guidelines to doctors and pharmacists to cap the amount of pills that can be dispensed at one time.

However, it's still seeking expert advice on what those limits should be, she said.

But there's no question that public dollars are being abused, she said. In once case, 2,000 OxyContin pills were dispensed to a single patient under the provincial program that funds medications for seniors, welfare recipients and people with disabilities, she said.

The new measures will also include a computer tracking system that would monitor how much of the drug is going out by transmitting every prescription into a provincial database, which will send out an alert if someone tries to fill a prescription for the same drug two days in a row.

The idea is to expand an existing online system for drugs prescribed under a provincial program that funds medications for seniors, welfare recipients and people with disabilities, Stevenson said.

Pharmacists who dispense publicly funded drugs enter the claims in the system, which is used by the government to track and reimburse drug costs. It also alerts the pharmacist to certain claims, such as a prescription that's filled too soon, she said.

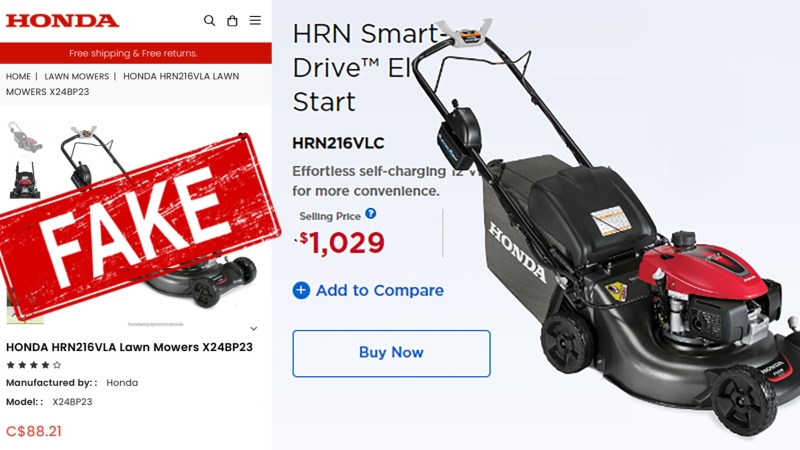

But those who are trying to get their hands on large quantities of the drug will game the system by getting a prescription through the public drug plan one day, and a private plan the next, she said.

"So what that says is that there's a real need to try to capture, at some level, the narcotic for all Ontarians," Stevenson added.

The ministry is currently working out the details of a province-wide tracking system and is still developing the new guidelines dealing with OxyContin and other narcotics, she said.

It's aiming to implement the new measures in the coming months, but it can't commit to a timeline just yet, she said.

Matthews said she's prepared to move ahead as soon as the details are finalized.

"There are always hurdles in getting things done," she added. "But I think this is important enough to take down any hurdles that need to be taken down."

It's not just the government that wants to see quick action to restrict OxyContin, Stevenson said. Many people came forward to tell their stories when the ministry formed its narcotics advisory panel last April.

"We heard from individuals on First Nations communities, from parents who've lost loved ones to narcotic, to private plans who wrote in to us immediately and said, 'We all have the same problem,"' Stevenson said.

"It's a real call, quite frankly, from the public that we need to do something."

Part of the problem is that OxyContin comes in high-strength doses where 35 per cent of the drug "hits you right away," said Dr. Peter Selby, director of addiction programs at Toronto's Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

The drug's slow-release mechanism is easily overridden just by crushing the pill, he added.

"Just the design of the drug itself makes it addictive," he said. "Secondly, you look at a vulnerable population who has pain or psychological pain, puts that person at risk."

A recent study on drug use among Ontario students found that one in five teenage girls admitted to using an opioid painkiller without a prescription, with many users getting the drugs from home.

Dr. Jurgen Rehm, a scientist at CAMH who co-wrote the study, said many teen users likely rummage thorough the medicine cabinet and use whatever prescription pain pills they find.

The new measures are a good first step, but addicts need treatment if they're to kick the habit, said Selby.

"If you just create restrictions, if somebody is addicted, will you create other worse compensatory behaviours if you don't have an out for that person?" he said.

"So any kind of monitoring should have not just, 'No, you can't get this medication' but 'Well, you might be addicted. Get an assessment. Go to treatment."'