TORONTO -- On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization added a weighty word to the uncontrolled spread of COVID-19 around the globe: pandemic.

The declaration proved to be the beginning of the end of life as we knew it. Now one year later, as masks are as essential as our wallet when we leave the house and we obsessively sanitize and wash our hands, did you think our collective lives would still be in limbo?

WE’RE GOING TO BE HERE A WHILE

Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health expected a marathon fight against the insidious SARS-CoV-2 virus, thinking the outbreak would stretch into late summer or fall of last year.

“I didn’t know it was an ultramarathon,” Dr. David Williams told CTV News Toronto.

The grandfather of four - who was supposed to retire in February – says initially he and his team stuck to the methods learned from Toronto’s 2003 SARS outbreak, but the unprecedented situation forced them to perpetually adapt and modify as new data rolled in. There have been big lessons learned.

“What we thought were readily available supplies, were not readily available… the global supply chain that seemed so wide and vibrant, isn’t,” Williams said.

He says he doesn’t have major regrets over the province’s response, but admits underestimating the influence of what was happening in the rest of the world.

“We were assuming that people in other jurisdictions knew what’s going on in their respective jurisdictions, that their methods of vigilance and testing were equal to ours. That was not the case,” Williams said when asked what he would have done differently. “Maybe we had to move quickly of limiting and restricting right from the get go.”

VACCINES CAN NOW BE MADE IN LESS THAN A YEAR

In those early days of the pandemic, there was an “a-ha” moment for virologist Dr. Arinjay Banerjee in a high-containment lab at McMaster University.

“I did get excited when I saw that we could isolate the virus… When I looked under the microscope I saw that the cells were dying,” Banerjee recalled.

With a background on coronaviruses, Banerjee and his small team worked quickly to isolate the COVID-19 virus, which allowed for critical research into how to control it.

“That was weighing very heavily on all of our shoulders,” he said.

For all his expertise, never did Banerjee expect that in under a year, a vaccine would be possible.

“We haven’t had a vaccine made and tested so robustly and implanted at a population level so quickly. This might be the biggest scientific achievement of my lifetime. You’ve had a pandemic and in less than a year’s time, you’ve got vaccines against it.”

He’s in awe of the achievement and grateful the outbreak wasn’t a different type of coronavirus.

“If you think of worst case scenario, SARS coronavirus is a wimpy coronavirus compared to a MERS coronavirus, so that gives me hope that the vaccines and all of these therapeutics coming out will take care of the virus,” Banerjee said.

PRE-SYMPTOMATIC AND ASYMPTOMATIC TRANSMISSION

Dr. Susy Hota trained for an outbreak like this, but never actually expected to see it come to life before her.

“It was pure adrenaline,” she recalled to CTV News Toronto.

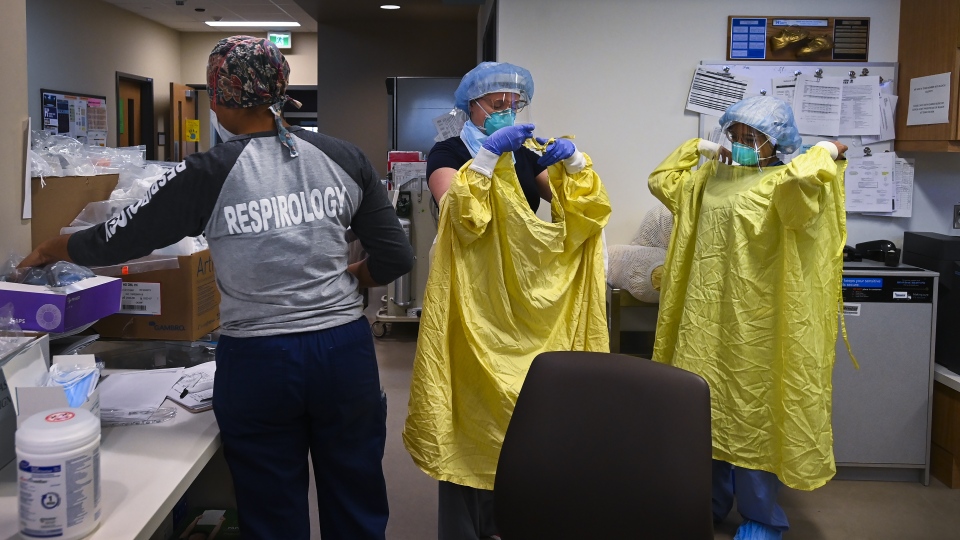

A monumental task as the Medical Director of Infection Prevention and Control at the University Health Network was to identify every single individual that could walk through the hospital doors and possibly have the novel coronavirus – which they didn’t know much about.

“At this time last year we didn’t know if people could transmit the virus before they got symptoms and that is such an important question to answer because so many of our assumptions and our processes were based upon identifying symptoms and isolating people at that time,” Hota said.

She says the moment they discovered people could be infectious in the days before they developed symptoms and be completely asymptomatic yet still transmit the deadly virus to others, “It changed the game entirely.”

Another evolution of understanding surrounds environmental contamination. Hota remembers there was a focus around excessively cleaning surfaces. Studies have shown the virus can live on certain surfaces for hours, days, even weeks.

All that time you may have spent cleaning your groceries didn’t hurt, but the hospital epidemiologist notes, “What we know now is that most of that is not infectious to others… It’s not the main way that you transmit from person to person through contamination of the environment.”

She stresses cleaning your hands is still important because high-touch surfaces could have virus on them. However, “Really the main way people are getting this is the respiratory route, which we knew about in the beginning as well,” Hota said.

MASKS WORK

Who would have thought we’d suppress the seasonal flu this year. Turns out it was no match for our relentless mask-wearing, social distancing, and constant hand washing.

Public health officials were initially concerned the public would raid mask supplies and did not advocate for widespread mask use among Ontario residents.

The science has since evolved amid a flood of data on the benefits of an array of face coverings, from medical grade to the homemade cloth variety.

ESTIMATES ARE JUST THAT

Do you find the numbers dizzying yet? The daily case counts have been both dismaying and exciting – depending on which part of which wave we were experiencing.

Ontario’s COVID-19 death toll – 7109 as of Thursday – has been heart wrenching and numbing as we long for the grim tally to finally stop. And without a crystal ball, the periodical modelling on where this pandemic could go has been a means to predict our potential future. Fortunately, at least here in Ontario, the estimates have not all panned out.

The Chief Medical Officer of Health points out to CTV News Toronto they expected a “mild pandemic” would mean 10 per cent of Ontario infected by COVID-19 after a year. That’s nearly 1.5 million people. Yet to date, more than 313,000 have been diagnosed with the disease.

“Through our public health measures, by carrying out steps and in working with our public… we together brought those numbers down,” Williams said.