Drug toxicity deaths in Toronto continue to surge since COVID-19 pandemic

Rosalie, from the EMMIS street intervention team, wears Naloxone, an overdose medication, during her tour on Monday, October 23, 2023 in Montreal. (Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press)

Rosalie, from the EMMIS street intervention team, wears Naloxone, an overdose medication, during her tour on Monday, October 23, 2023 in Montreal. (Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press)

The number of people dying after consuming unregulated drugs in Toronto continues to be significantly higher than before the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the latest preliminary data released by Toronto Public Health, there were 523 opioid toxicity deaths in the city in 2023 – a 74 per cent increase from 2019 when Toronto recorded 301 deaths due to toxic drugs.

At this point, 427 of the suspected 523 drug-related deaths in Toronto have been deemed accidental. Public health says that almost half were individuals aged 25 to 44 years, 54 per cent of those individuals lived in a private dwelling, and 39 per cent of those who died were in their homes at the time of their death.

The latest numbers are up slightly from 2022, which saw 510 people die after consuming unregulated drugs: 507 of those deaths were confirmed by Public Health Ontario and the Officer of the Chief Coroner for Ontario, while the remaining three are being considered probable.

In 2021, during the height of the pandemic, Toronto saw a record-breaking 591 confirmed drug toxicity deaths.

“The continued loss of life to the ongoing drug toxicity epidemic is devastating and has left a profound and painful impact on so many of us in our community. This is more than a public health issue – it’s a human tragedy that demands we respond with empathy, care and compassion,” Toronto’s Medical Office of Health Dr. Eileen de Villa said in a news release.

The health unit noted that Toronto’s unregulated drug supply is increasingly toxic and contaminated with unexpected and dangerous substances.

So far this year, TPH has issued four drug alerts advising those who use drugs to along with harm reduction organizations and public health units about presence of potent toxic substances in the unregulated drug supply as well as increases in suspected overdoses.

Public health said that one of the key ways to address this crisis is supervised consumption services, clinical spaces for those who use drugs to consume them in the presence of trained health professionals. Ten such sites current exist in Toronto.

“Evidence shows that SCSs save lives, connect people to social services and are proven pathways to treatment,” said TPH, which has long called for “greater access to a full continuum of evidence-based healthcare services including prevention, treatment and harm reduction supports.”

“(We) remain a willing partner to explore collaborative solutions to this urgent public health issue,” it said.

Harm reduction worker weighs in on elevated drug toxicity deaths

Pat Fifield, a harm reduction coordinator with Street Health, believes that there are two factors contributing to the ongoing high number of drug toxicity deaths being seen in Toronto.

The first one is how people are consuming drugs, which he said in about half of the cases is through inhalation.

Fifield, who works at a supervised consumption program at a shelter, said that there is a perception even among the drug-using community that this method is safer than taking drugs orally or by injection. In the end, no drugs are entirely safe, no matter how they’re consumed, he said.

Currently, the only supervised drug inhalation program in Ontario is located at Casey House and is only open to registered clients of the downtown Toronto hospital.

He said that discussions are underway at this time about what supervised inhalation could look like at some of the city’s shelter sites.

Secondly, Fifield said that the increased toxicity and unpredictability of the substances out there is killing people who use drugs more than ever before.

Fifield has worked in harm reduction for about a decade and said in that time he’s seen heroin users survive for several years as the supply was mostly stable, whereas many of those who are consuming fentanyl or what they believe is fentanyl are dying at a much quicker rate.

“We have really toxic drugs on the streets right now. We’re seeing so many kinds of unwanted substances that are showing up in the drug supply,” he said.

“It’s impossible nowadays to know what you’re taking and to control your dose and your usage.”

Fifield added that many of the community members he knows and supports value and are alive today because of the city’s drug checking service, a free and anonymous public health service offered at five harm reduction agencies in Toronto’s downtown core.

“People want to know what’s in their drugs,” he said, adding this service is also helping harm reduction workers to better respond to drug overdoses and poisonings.

“I try to compare notes with my colleagues, but it’s hard to get a full handle on the situation as the drugs can be completely different from one end of town to the other.”

Fifield said without a total overhaul of the current drug policy and a new comprehensive and more humane one in its place people will continue to die of drug toxicity at an alarming rate.

“Every overdose death is a policy failure and every one of those deaths is preventable…. We need people in power who are willing to go to bat,” he said, adding that more supervised consumption services are essential to preventing deaths coupled with more safer supply programs, treatment and detox options, and the decriminalization of the small possession of drugs.

“Nobody is taking this as serious as it needs to be taken. … It’s literally an ongoing, unfolding health crisis,” said Fifield.

“A lot of harm reduction workers feel like we’re pushing a big rock up a hill. We’re not getting where we need to be.”

The lack of action, he said, means that people he’s worked hard to develop relationships with and help are dying.

“I can’t count the number of people I’ve lost since I started doing this work,” he shared.

“That’s the hardest part of my job.”

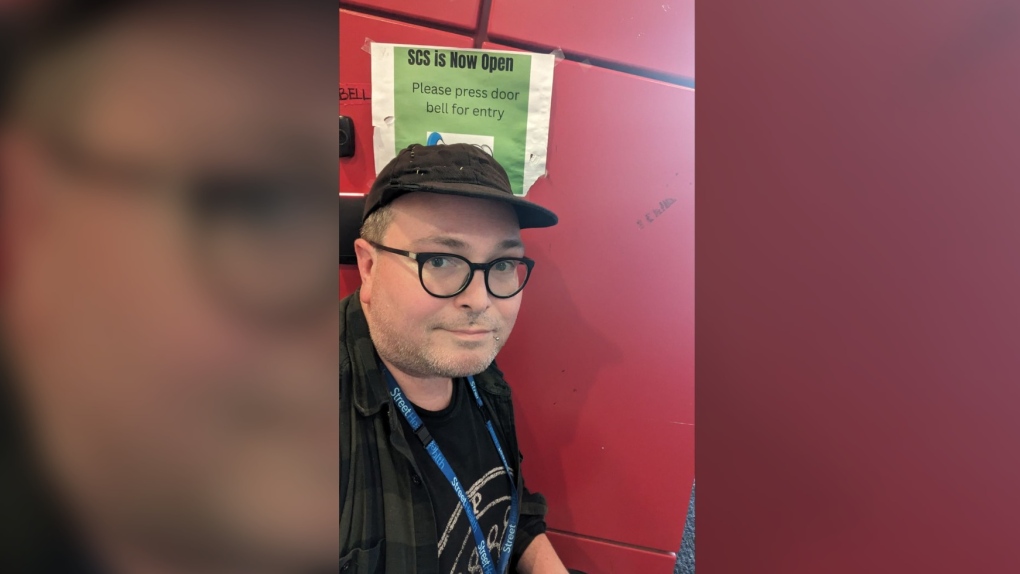

Pat Fifield is a harm reduction coordinator with Street Health who works at a supervised consumption service at a Toronto shelter (Supplied)

Pat Fifield is a harm reduction coordinator with Street Health who works at a supervised consumption service at a Toronto shelter (Supplied)

According to Health Canada, there were 42,494 apparent opioid toxicity deaths reported between January 2016 and September 2023. The vast majority of those deaths occurred in British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario and were mostly males between the age of 20 and 59.

Most of those who died had consumed either fentanyl, another non-pharmaceutical opioid, or a stimulant, Health Canada said.

Canada started recording accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths in 2016.

Fifield noted that drug use is something that affects people from all walks of life, backgrounds, and social classes.

“It’s unfair and inaccurate to say that it’s a problem among a certain segment of the population,” he said.

A Naloxone anti-overdose kit is held in downtown Vancouver, Friday, Feb. 10, 2017. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward)

A Naloxone anti-overdose kit is held in downtown Vancouver, Friday, Feb. 10, 2017. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward)

Coun. Chris Moise, who chairs the Toronto Board of Health, said that “every life lost to this crisis is not only tragic but also preventable.”

He said that increasing funding and access to treatment options, including the opening of a 24/7 stabilization crisis centre, is “essential to tackling the drug toxicity epidemic.”

This effort, however, requires the “coordinated efforts” of all three levels of government, he noted.

“This situation demands an immediate and collective call to action for all of us,” Moise said.

Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow, meanwhile, said community health and wellbeing is under serious threat due to the “toxic unregulated drug supply, coupled with the housing and affordability crisis.”

“Treatment is vital. We need the support and participation of all three levels of government to significantly reduce the devastating impact of the drug toxicity epidemic in Toronto and across Ontario,” she said in a release.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Driver who entered Canada 'without stopping' at B.C. border crossing arrested: police

A man who illegally blew through the Canada-U.S. border crossing in Surrey, B.C., Sunday morning has been arrested, according to authorities.

Canada closes 'flagpoling' loophole for temporary visa holders

Temporary residents of Canada will no longer be able to utilise the flagpoling process to initiate work or study permits, following a ban from the Canada Border Services Agency.

Nikki Glaser gets Golden Globes, 'Ozempic's biggest night,' underway. Zoe Saldana wins 1st award

Comedian Nikki Glaser kicked off what she called “Ozempic's biggest night,” the 82nd Golden Globes, with a promise: “I'm not here to roast you.”

'Absolutely devastating': Southern Manitoba golf course clubhouse burns for second time in 4 years

A golf course clubhouse in Morden, Man. went up in flames Sunday for the second time in less than four years, and mere days after its reopening from the previous fire was celebrated.

Thousands are without power due to winter storm hitting Newfoundland and Labrador

Massive waves slammed Newfoundland and Labrador's coastline on Sunday, as a powerful winter storm left thousands without power.

Man responsible for New Year's truck attack previously visited New Orleans, Ontario, Egypt: FBI

The man responsible for the truck attack in New Orleans on New Year's Day that killed 14 people visited the city twice before and recorded video of the French Quarter with hands-free glasses, an FBI official said Sunday.

The Vivienne, star of 'RuPaul's Drag Race UK', dies at 32

British reality show 'RuPaul's Drag Race UK' winner James Lee Williams, aged 32, popularly known as The Vivienne, has died.

Driving into Manhattan? That'll cost you, as new congestion toll starts Sunday

New York’s new toll for drivers entering the center of Manhattan debuted Sunday, meaning many people will pay US$9 to access its busiest part in peak hours.

WATCH Woman critically injured in explosive Ottawa crash caught on camera

Dashcam footage sent to CTV News shows a vehicle travelling at a high rate of speed in the wrong direction before striking and damaging a hydro pole.