You’re sitting on a TTC subway train, on your way to work, and the crackle of an overhead speaker blares through your headphones.

“Service is suspended on Line 1, both ways at College Station, due to a trespasser at track level,” the voice says.

Delays like these – passenger-related delays – totalled more than 17,000 minutes across the TTC’s four subway lines in 2016, according to statistics obtained by CTV News Toronto.

That amounts to approximately 12 whole days of trains sitting idle on the tracks waiting for TTC operators to get an all-clear.

James Ross, the TTC’s Deputy Chief Operating Officer, said he has seen it all.

“People will go down on the tracks late at night, maybe when they’re intoxicated, to relieve themselves on our tracks… at train stations where we don’t have restrooms,” he said

“People who faint on the train in the morning, people who have heart attacks, people who fall and think they’re okay but can’t get up when they get to their stop.”

Ross said that commuters are often quick to blame the TTC and don’t realize the culprit behind their Monday morning tardiness is actually a fellow rider.

“If we’re moving 1.7 million people a day, you have to expect a certain number of delays. People get ill, people get into disagreements with each other, people are people,” he said.

But it’s not always the passenger’s fault.

More than 50 per cent of delays riders experience are due to mechanical issues and signal failures. This means on 2016, the total amount of time lost due to delays, passenger-related issues included, was more than 38,000 minutes.

That adds up to approximately 26 days.

The TTC is taking steps to fix some of their ongoing issues.

Much of the TTC’s signaling system was installed in the 1950s. The TTC is in the process of replacing the entire system on Line 1 but that won’t be completed until 2020. Moreover, the replacement of the signal system on Line 2, which dates back to 1966, will likely take even longer, as funding for that project has not yet been set aside.

The TTC’s ‘Station Transformation Model’ laid out a target in 2014 to reduce delays by 50 per cent.

Ross said though the TTC has a long way to go to meet their target, some delays are out of control, including how long it takes to clear subways for operation after an incident.

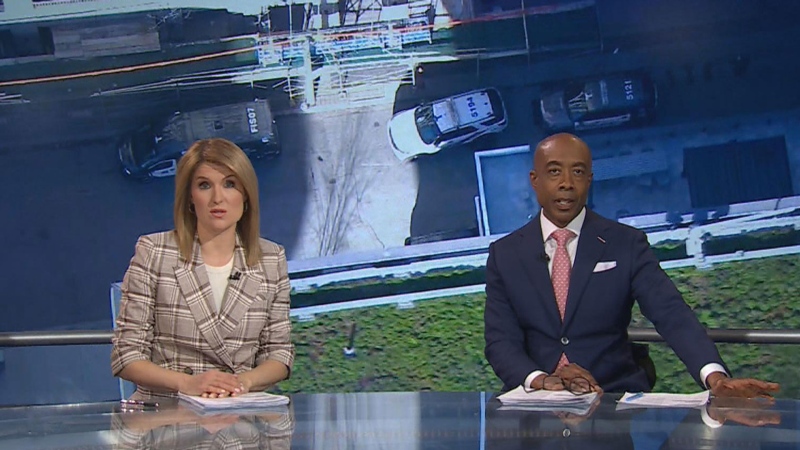

He explained the TTC’s response to each passenger-related delay starts at the transit control centre where officials cut power to the track.

Sitting flanked by security cameras, TTC officials watch the situation unfold as a second crew hurries to the site of the delay to survey the situation and, eventually, give the go-ahead to restore power.

Despite the seemingly straightforward procedure, Ross said the time it takes for officials to deem the tracks safe for service again adds up – and quickly.

“People who faint on the train in the morning, people who have heart attacks, people who fall and think they’re okay but can’t get up when they get to their stop,” he said.

“That’s still taken a 10 minute delay. And when you’re trying to deliver a train every two minutes and 20 seconds, 10 minutes is a long time.”

Ross said the TTC has undertaken a number of initiatives to combat the growing number of interruptions, including better staffing at stations.

“In peak periods at Yonge and Bloor, and St. George, we have a Toronto Paramedics Service medic that stands by at the station. So if we have a passenger illness, they can come and help us and we can get going a little bit faster,” he said. “If we can get there faster, hopefully we can clear it faster.”

“We’re mostly focused on safety, getting them the help that they need and then clearing the delay. The longer a train sits in one spot, the following trains start to back up just like any other means of transportation. Then you have to initiate turn backs and it spirals back from there.”

Sometimes the delays bring stories staff at TTC won’t soon forget.

“One person chased a train through a tunnel hoping she’d get her purse back,” he said.

“I think everybody knows that it’s not a good idea to jump down on the tracks. I think they weigh their options at that moment and take the chance.”

In the past, riders have also used the tracks as a “short cut” to get from the eastbound side to the westbound side or vice versa.

The risky business is a criminal offence, Ross said, as it’s contrary to the TTC’s first bylaw.

“It’s really not worth it,” he said. “Your cell phone’s not worth your life.”