Ontario's nursing shortage has been an issue for years. Why weren't we prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic?

In mid-January, as a new wave of COVID-19 passed through Ontario, driven by the Omicron variant, 477 patients would find themselves in an ICU with the disease.

Health Minister Christine Elliott told reporters at the time that approximately 600 ICU beds remained available across Ontario, and noted that nearly 500 additional beds could be added if required.

And while the number of patients in an Ontario ICU with COVID-19 has since grown to 626, word of the extra ICU capacity was welcome news to the public, who had been warned about the dangers of overwhelming the province’s health-care network.

But one ICU nurse says that without proper staffing, those beds are as useful as “the beds we have at home.”

“I work at different facilities, and every now and then, I walk around and I’m like, ‘oh, we have a lot of beds.’ But then there’s a code blue, a cardiac arrest, and we can’t even take the patient because we don’t have nurses,” said Birgit Umaigba, an ICU nurse and clinical course director at Centennial College.

The shortage of nurses in Ontario is not a new phenomenon.

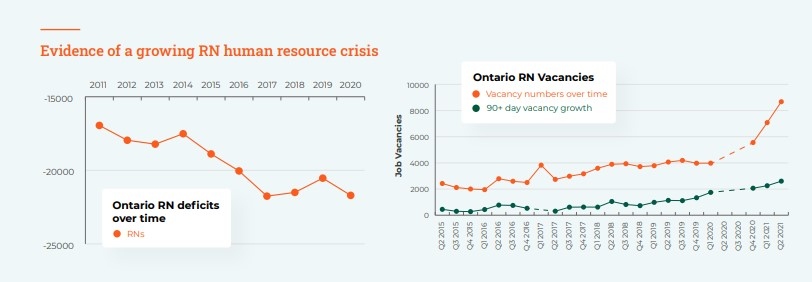

In fact, just as the province found itself in the midst of a global pandemic in March of 2020, the province was nearly 22,000 registered nurses (RN) short of the rest of Canada on a per-capita basis, according to the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO).

Before that, data collected by the group shows that RNs in Ontario had been steadily leaving the public workforce since early 2015 and vacancies neared 9,000 by the middle of 2021.

“What has happened, since the time of [former Ontario Premier] Mike Harris—that’s how long this has gone—is that RNs have been replaced, replaced, replaced,” RNAO CEO Doris Grinspun told CTV News Toronto during a video interview.

(Ontario's RN Understaffing Crisis: Impact and Solution SOURCE: RNAO)

The shortage has been ongoing for decades and has been driven by what the group calls misguided government and employer policies “designed to lower the proportion of RNs employed in Ontario.”

“Nursing doesn’t really allow people flexible work hours, and most nurses are woman,” Umaigba explained. “A lot of those women do have children. So, there’s always been a shortage because most people would rather work part-time, casual or with agencies just to accommodate their schedules.”

And the shortage could get even worse due to pandemic-related stress on the job.

According to an RNAO survey of 2,100 RNs in Ontario from March 31, more than 95 per cent of all respondents said the pandemic had affected their work, with a majority of nurses reporting high or very high stress levels.

What’s more, at least 13 per cent of RNs between the ages of 26-35 reported they were very likely to leave the profession after the pandemic and 4.5 per cent of respondents who are late career nurses say they plan to retire now or immediately after the pandemic.

“Now, it’s just, out of control. It’s a nightmare. It’s a disaster. It’s an area that was never addressed and it’s affecting nurses and patients alike,” Umaigba said.

Advocates say that more could be done now by the current government to address the issue and agree that repealing Bill 124, which was introduced by the Ford Government back in 2019 and limits wage increases for public sector workers to one per cent per year over the course of a three-year moderation period, would be a good start.

Federal data shows that the median hourly rate for an RN in Ontario is $39, meaning that under Bill 124, an RN could expect their wage to increase to just $39.39 in one calendar year. That wage would increase to $40.17 at the end of the bill’s three-year moderation period.

Scrapping the legislation would not only help to retain nurses currently working in the filed, but also make the profession more appearing to aspiring health-care workers, Umaigba said.

“If the working conditions continue like this, people, yes, they will come and we’ll have new grads coming in. But, they’re also going to run away and feel tired, disrespected, and just leave,” she said.

“We know what the solutions are, but I don’t know why this government is actually refusing to implement the solutions suggesting by so many nursing leaders and advocates out there.”

In a statement to CTV News Toronto, the Ministry of Health said Ontario added more than 6,700 health-care workers and staff to the system since the start of the pandemic.

"We are working to add 6,000 more health care workers before the end of March 2022," a spokesperson said.

The Ministry of Health also said they are working with sector partners to implement a comprehensive strategy focused on recruiting and retaining health care professionals.

According to the province’s fall economic outlook, the government plans to invest $342 million over the next five years to add over 13,000 workers to Ontario’s health care system, including over 5,000 new and upskilled registered nurses and registered practical nurses as well as 8,000 personal support workers.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Trudeau's 2024: Did the PM become less popular this year?

Justin Trudeau’s numbers have been relatively steady this calendar year, but they've also been at their worst, according to tracking data from CTV News pollster Nik Nanos.

Manhunt underway after woman, 23, allegedly kidnapped, found alive in river

A woman in her 20s who was possibly abducted by her ex is in hospital after the car she was in plunged into the Richelieu River.

Toronto firefighters rescue man who fell into sinkhole in Yorkville

A man who fell into a sinkhole in Yorkville on a snowy Friday night in Toronto has been rescued after being stuck in the ground for roughly half an hour.

Wild boar hybrid identified near Fort Macleod, Alta.

Acting on information, an investigation by the Municipal District of Willow Creek's Agricultural Services Board (ASB) found a small population of wild boar hybrids being farmed near Fort Macleod.

Summer McIntosh makes guest appearance in 'The Nutcracker'

Summer McIntosh made a splash during her guest appearance in The National Ballet of Canada’s production of 'The Nutcracker.'

Death toll in attack on Christmas market in Germany rises to 5 and more than 200 injured

Germans on Saturday mourned both the victims and their shaken sense of security after a Saudi doctor intentionally drove into a Christmas market teeming with holiday shoppers, killing at least five people, including a small child, and wounding at least 200 others.

Overheated immigration system needed 'discipline' infusion: minister

An 'overheated' immigration system that admitted record numbers of newcomers to the country has harmed Canada's decades-old consensus on the benefits of immigration, Immigration Minister Marc Miller said, as he reflected on the changes in his department in a year-end interview.

30 people die in a crash between a passenger bus and a truck in Brazil

A crash between a passenger bus and a truck early Saturday killed 30 people on a highway in Minas Gerais, a state in southeastern Brazil, officials said.

Back on air: John Vennavally-Rao on reclaiming his career while living with cancer

'In February, there was a time when I thought my career as a TV reporter was over,' CTV News reporter and anchor John Vennavally-Rao writes.