A man who refused to take the oath of citizenship, because of his opposition to the monarchy, has died with his decades-long dream of becoming a Canadian unfulfilled.

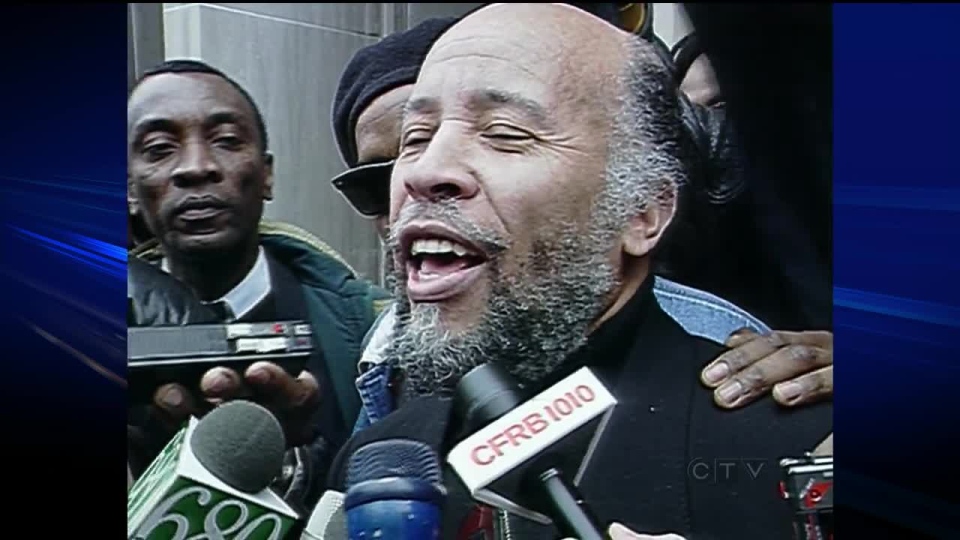

Toronto civil-rights lawyer Charles Roach, who immigrated from Trinidad and Tobago more than half a century ago, died Tuesday after a battle with brain cancer. He was 79.

Roach had fought to change the country's citizenship requirements to allow people to swear an oath to Canada instead of the throne, which he said represented a legacy of oppression, imperialism and racism.

A New Democrat MP is now calling on Ottawa to make Roach, who was a prominent community activist, a Canadian citizen posthumously. In a statement Wednesday to the House of Commons, Andrew Cash urged the government to honour Roach with the status.

"People may not agree with the views that Mr. Roach expressed around this issue, but I think you can disagree and still respect the man and his contributions," the Toronto MP said in an interview from Ottawa.

Cash said he tried asking Immigration Minister Jason Kenney last week to fulfil Roach's dying wish to become a Canadian citizen by pledging allegiance to Canada, instead of the Queen. He said Kenney did not respond to the request.

A close friend and colleague of Roach's hopes the government will proceed with the latest request to grant him the posthumous honour.

"Well, one might say, 'Better late than never,' " said Peter Rosenthal, a lawyer who knew Roach for nearly 40 years.

"Of course, I was hoping that would happen while Mr. Roach was alive, so that he would have the positive feeling of it occurring."

But Immigration Canada quickly shut the door on any chance that Roach would be given his citizenship after death.

"There is no provision under the Citizenship Act for the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration to grant citizenship posthumously," a departmental spokesman wrote in an email Wednesday.

The department said the oath is mandatory under the act and any amendment would first have to pass through Parliament.

Roach had pushed for decades to see such a change.

Rosenthal said Roach's desire to become a Canadian citizen was extremely important to him, but his conscience wouldn't allow him to swear allegiance to the Queen.

His stance against uttering the oath nearly forced him to give up his profession because of an old requirement that said he had to be a Canadian to practise law. Rosenthal said Roach even declined an opportunity to become a judge over his refusal to take the oath.

Roach's decision to remain non-Canadian, despite the fact he moved to Canada in 1955, had other costs.

Refusing to swear allegiance is a sacrifice, as potential Canadians give up numerous rights of citizenship -- including the right to vote and to run for public office.

Non-citizens cannot enjoy the travelling freedoms of a Canadian passport, all while paying the same taxes as regular citizens. Technically, they can even be deported for committing certain crimes.

Roach, who said he believed there were many other residents of Canada like him, initiated the first of several court challenges to remove the royal reference from the oath in the 1990s.

He wanted Canada to follow Australia, a Commonwealth country that amended its citizenship oath in the 1990s by replacing its promise to the monarchy with a pledge of loyalty to "Australia and its people."

His latest legal battle will continue after his death because there are other applicants, said Rosenthal, who will argue the case before the Ontario Superior Court.

The next court date is July.

Rosenthal will argue that the citizenship oath violates freedom of conscience and equality rights under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

His last conversation with Roach was Monday, when he updated him on the case.

"He knew he wasn't going to be around to hear it," said Rosenthal in an interview from Toronto.

He added that Roach had attended a hearing for the case in May -- just days after he had suffered a stroke. Roach had a tumour removed from his brain in March.

"Becoming a Canadian citizen was important to him because everything he did in life, really, as an adult was done in Canada and he really wanted that participation."

Every new citizen 14 years and older must recite and sign the oath, which more than 140,000 people took in 2010.

To become a Canadian citizen, a candidate must pledge the following: "I, ..., do swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, Queen of Canada, Her Heirs and Successors. So help me God."

Roach told The Canadian Press last year that he was offended by the principle.

"I don't believe that anyone should have a political status just because of your birth and I feel strongly about that," he said in a June 2011 interview.

"For that reason, I wouldn't take an oath to any such institution, which is based on race and religion."

Roach made headlines in 2011 after he organized a demonstration to protest Prince William and Kate's presence at a Canada Day citizenship ceremony in Ottawa.

He was among about a dozen people who strummed guitars and waved placards outside the building to decry having to swear the mandatory oath of allegiance to the Queen. The group also staged a mock citizenship ceremony where fake applicants took an oath to Canada, rather than the monarchy.

"We were booed by 500 royalists, but dozens gave the thumbs up," Roach wrote a few days later in an email to The Canadian Press.

Roach was an active leader in Toronto, where he helped found the Caribana festival, which is now known as the Scotiabank Caribbean Carnival. It's the largest cultural festival of its kind in North America, featuring a colourful parade full of Caribbean music and thousands of dancers.

Roach also helped form the Black Action Defence Committee, which pushed for independent investigations after several black people were killed by police in the Toronto area more than 20 years ago.

Rosenthal credits the committee's efforts for prompting the creation of Ontario's Special Investigations Unit.

The civilian-led unit, which is independent of police, investigates cases where officers seriously injure or kill people. It replaced the former process, which once saw police forces investigate other forces.

Rosenthal said Roach's dedication to civil rights will be missed.

"It leaves a huge hole, but I hope that his memory will inspire people to fill that gap," he said.

Roach is survived by his wife, June, his four children and several grandchildren.