TORONTO -- Public health experts are calling the tiered plan for dealing with COVID-19 shutdown in Ontario dangerous, "scientifically illiterate" and "dismaying," saying that the premier's new system will light an inferno rather than snuff out the pandemic.

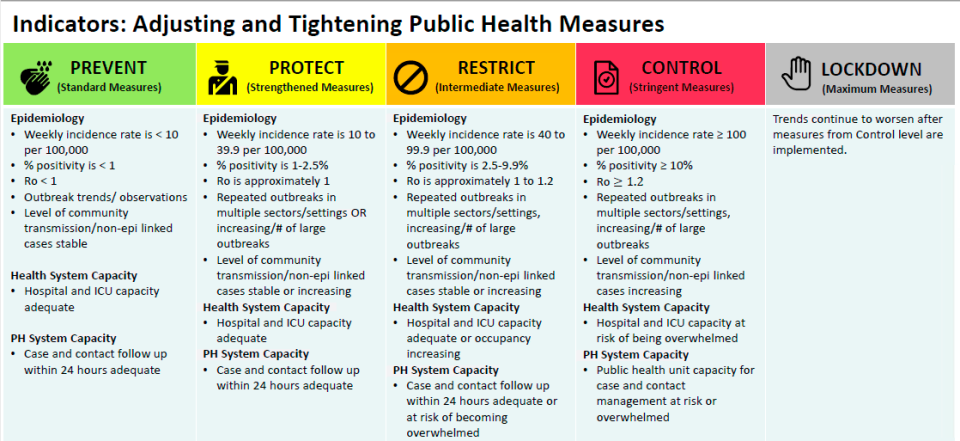

The new framework released Tuesday will place each of Ontario’s 34 public health units into one of five categories based on a series of trends, including positivity rate, weekly incident rates, level of community transmission, hospital and intensive care unit capacity and the disease’s reproductive rate.

“The concepts of clear metrics, a clear roadmap for what might happen with respect to closures, that's smart,” Dr. Colin Furness, an infection control epidemiologist at the University of Toronto, told CTV News Toronto. “That said, the implementation is dismaying. It’s dismaying because of the criteria, the thresholds that are in my estimation unacceptable.”

The five categories are colour coded, with green being the lowest measure, followed by yellow, orange, red and grey, which signifies a total lockdown.

The new system is expected to be implemented on Saturday, and would see Ottawa, York Region and Peel Region move to an orange, or restrict, level in which indoor dining and gyms are allowed to reopen with slight modifications.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford said the plan was “about early intervention to avoid getting to the red zone.”

“If there's smoke, you go in there and you put the fire out, compared to waiting until there’s a big inferno and then you go in and react. This is about early detection and early prevention and then we can act,” he said.

Thresholds for moving between categories are ‘dangerously high’

While many public health experts agree with the concept of having a set of guidelines for when health units need to implement further restrictions, many feel as though the plan presented this week is lacking in details and includes dangerously high thresholds that have to be met.

“The fire is going to go out of control,” said Dr. Anna Banerji, infectious disease specialist and associate professor of pediatrics with Dalla Lana School of Public Health. “They're watching one fire in one area, and they've got their back turned to the inferno behind them.”

Multiple experts said that the 10 per cent positivity rate and the 100 per 100,000 weekly incident rates needed to move to a red (control) level is too high.

Regions that are within the red level are expected to revert back to a version of the province’s modified Stage 2 approach, which means limiting indoor dining to 10 people and closes most gyms.

Amir Attaran, a professor of law and public health at the University of Ottawa, says that the thresholds for moving to a control level are “absurdly, dangerously high.”

“The criteria there for weekly incidents and for test positivity aren't met in the vast majority of the United States,” he said.

“So what the province is saying is that the situation in Ontario has to deteriorate beyond most of the United States, which as we know is a disaster, before they will implement that degree of control.”

Attaran added that if Ottawa, for example, reported a weekly average of 100 new COVID-19 cases, leading to a weekly incident rate of 10 per 100,000, the city would be considered for the green (prevent) level.

“Meaning, there's no problem in Ottawa,” he said. “Now of course everyone in their right mind knows there's a problem in Ottawa because we surpassed our maximum number of cases quite recently even compared to what we had back in in March, April and May.”

As of Thursday, Ontario’s positivity rate stands at 2.8 per cent. In Toronto, where the majority of COVID-19 cases have been reported, that rate jumps to about 4.8 per cent.

Toronto is the only region that requested staying in the province’s modified Stage 2—or red level—for another week before moving forward with the new system.

The problem with using the positivity rate as a measurement is that not everyone who contracts COVID-19 gets tested and those that do, another expert said, sometimes don’t get a positive result.

Banerji says that she doesn’t think the government is recognizing the fact that if someone tests negative one day, they could be in the incubation period and be spreading the disease without their knowledge.

“The virus has certain capacities on its own,” she said. “It's a highly infectious virus and all around the world, even if people are doing their very best, this is a hard virus to contain.”

She also said there are a high number of false negative tests occurring in patients that most likely have the disease, which could impact a region’s positivity rates.

“All those people, even if they have a negative test, they should be staying at home and acting as if they have COVID,” she said. “Anything that could possibly be COVID should be treated as if it's COVID, because if you're only doing contact tracing on, you know 70 per cent with 30 per cent of the people with COVID are having negative tests, that's a lost opportunity.”

“You're allowing all these people to be out there, spreading it a because you're only focused on the positive test and so I think that's a huge mistake.”

Speaking to reporters on Friday, Ontario Health Minister Christine Elliott said that criteria was designed based on consultations from Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. David Williams and other health officials.

"We need to continue to be consistent with the decisions that we're making," she said. "This isn't just the advice of one person, not every public health doctor is going to agree with this, but these are solid recommendations that have been brought forward by any number of public health experts and that's what established the framework for us."

She added that the framework provides the public with information so that each individual can make their own choices about how to act.

Criteria for thresholds ‘scientifically illiterate’ and not clear

What is not clear in the tiered system presented by the Ontario government is how many of the criteria in each column a region must meet before moving on to a new level.

Attaran says the lack of an “and/or” in the tables is troubling. He wonders if regions need to have a positivity rate of more than 10 per cent, a weekly incident rate of 100 cases per 100,000 and have repeated outbreaks in multiple sectors in order for more measures to be put in place—or is merely achieving one of the criteria enough?

“Under epidemiology, where you've got five bullet points, do you need all five satisfied? Do you need one satisfied? What do you need?” he said. “This is gibberish, which belongs on the back of a cereal box and not in any serious province’s public health planning.”

The ministry of health did not provide clarity when asked by CTV News Toronto on Thursday, saying only that the government “will use all these indicators to continually assess the impact of public health measures applied to public health unit regions for 28 days, or two COVID-19 incubation periods.”

“Final decisions on moving public health unit regions into the framework will be made by the government based on updated data and in consultation with the chief medical officer of health, local medical officers of health and other health experts,” a spokesperson said.

Attaran also said that the plan is “scientifically illiterate,” referencing the use of the basic reproduction number (R0), which doesn’t actually change.

In the documents presented by the provincial government, in the yellow level the R0 would be about equal to a value of one. In the orange level, it is between one and 1.2 and in the red level, it is more than 1.2.

“R0 does not change, ever,” he said. “R0 does not go up and down by the day. There's a different variable called Rt that goes up and down. So I don't know what they're talking about but this is just plain scientific illiteracy on their part.”

"These guys are such amateurs they don't even seem to have understood the first chapter of an epidemiology textbook"

R0 is the number of infections that can be generated from one case of a disease, without any public health measures in place. Furness explains it’s a bit like an estimate of how contagious a disease or virus is.

Rt is the effective reproduction number and is more representative of what is occurring in the moment, based on public measures put in place to help curb transmission.

“If it stays below one, the outbreak dies out, because every new case causes less than one more,” Furness said. “As soon as it’s just a teeny tiny bit above one, eventually everyone gets sick.”

Ontario’s Rt value stands at about 1.08 while Toronto’s is slightly higher at 1.09.

On Friday, a spokesperson from the ministry of health said that the use of R0 in the framework was a typo, and that it should have been the effective reproduction number used as a variable for the tiered system.

The mistake is being corrected in future versions of the framework, they said.

The government did not say how they were alerted to the mistake.

At what point will the health-care system by overwhelmed?

The Ontario Medical Association (OMA) told CTV News Toronto that reaction is mixed among its members towards the tired system.

“We are extremely grateful that there is the creation of a guideline outlining when regions can take their loosened pandemic restrictions, as it provides clarity for patients and health-care professionals, it provides the transparency that everyone's been looking for,” OMA President Dr. Samantha Hill said.

“But I'm hearing concern about the effects of relaxing measures.”

Hill, who works at numerous hospitals in Toronto, said that on Thursday her surgeries were cancelled as a result of outbreaks.

“Of course the concern about that isn't just that people are waiting, it’s that while people are waiting they're suffering. And when they present later with the same disease processes, they're sicker, possibly less recoverable, and it costs the system more.”

“If you lift restrictions and increase the burden on a health-care system that's already struggling and stretched to its max, something has to give and that's going to wind up being all of that non-emergent care again and so we're worried about how we move forward and how we prioritize healthcare.”

According to Hill, further public health supports should be in place before the province eases restrictions. These supports include proactive testing, contact tracing and the ability to enforce regulations.

Without those supports in place, Hill worries that there could be further hospitalizations and worsening care.

“The concern is that we don't have the support needed for public health in the middle of a pandemic to loosen restrictions … We need to be able to find the disease rapidly and contain it when it is out there.”

Furness agrees that the most important metric in measuring the impact of COVID-19 is the extent to which the health-care system is in danger of being overwhelmed.

“Once that happens then then mortality goes way up.”

He said the most challenging part about a tiered system is that officials have to essentially look into a crystal ball to determine when to move a region to another threshold, as it generally takes about a month to see a change.

“When you change from orange to red, you're still going to have a month or so of increases in cases,” Furness said. “The change in trajectory for a contagious pandemic is slow so you actually have to think like a month or so ahead of time to say, well, at what point do we need to move from one stage to another, based on what we think is going to be happening actually a month from now.”

“And that's really why the criteria are really brutal. If you make the switch at 10 per cent positivity, then you may get to 30 per cent positivity before it starts to go back down.”

“That’s my fear.”