When digital data lives on after death: How to navigate questions of consent, privacy

When her son died unexpectedly a year and a half ago, a Toronto mother found herself at a loss trying to recover his cryptocurrency funds.

“His iPhone is locked, it’s with the photo recognition, and unfortunately we have not had any luck getting in,” caller Christina told NEWSTALK 1010. “We’ve been locked out of his accounts, we don’t even know what he had.”

- Download our app to get local alerts on your device

- Get the latest local updates right to your inbox

She had phoned in to weigh in on a CTV News Toronto report that revealed that increasingly families were turning to funeral homes for assistance in unlocking their loved one’s phone; hoping that through a fingerprint or face scan of the body, they could break in with biometrics.

A lack of access to digital accounts after death is becoming all too common, according to experts, who say that non-physical assets are often overlooked in estate planning. Half of Canadians don’t have a last will and testament, according to a recent poll by Angus Reid — let alone a proper plan for digital data.

“Often we don’t know what someone’s digital footprint is, where exactly they banked and you know, all the subscriptions they are paying for on their credit card account,” Erin Bury, co-founder and CEO of the online platform Willful told CTV News Toronto. “So it’s so crucial for executors and family members to have access to these digital accounts. “

Online tools like Willful and Epilogue encourage users to list digital assets and wishes as part of their estate planning, so that executors aren’t forced to hunt down online accounts that exist without a paper trail.

Password sharing can prevent the desperation that sends family members to funeral homes in search of a fingerprint or face-scan, but financial planners caution against listing those codes in the will as it becomes a public document.

Moreover, said estate planning lawyer Daniel Goldgut, password sharing is not advisable for specific types of tech-giant accounts.

“It violates the terms of service with those companies, so it’s not black and white,”Goldgut said. “The solution is being cobbled together right now.”

Goldgut co-founded Epilogue, which allows users to create a social media will. The platform points users to the pre-planning and legacy contact options available through Facebook, Google, and Apple, which allow the user to indicate what should happen to their digital data after death.

An online password is shown in this stock photo. (Valerie Potapova/Shutterstock.com)

An online password is shown in this stock photo. (Valerie Potapova/Shutterstock.com)

“Most of the big-tech companies right now actually give people the ability to do some pre-planning, and most people don’t know that at all,” Goldgut said.

Indicating consent for digital access ahead of time can also avoid a larger ethical dilemma for those left to handle the estate.

“There are a lot of privacy concerns,” said Charlene Chu, a University of Toronto assistant professor who specializes in technology for older adults.

“It is possible that people don’t want to share those things, and wouldn’t have given consent to share those things if they even were alive.”

Many people who use technology, Chu said, don’t fully understand the ramifications of where their digital data goes — and who might have access to it.

“I think if anything, there’s a larger call here, to just society in general, to think about how some of what we are doing online and what we’re doing using our digital devices could eventually be accessed by others after we have passed away.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

From outer space? Sask. farmers baffled after discovering strange wreckage in field

A family of fifth generation farmers from Ituna, Sask. are trying to find answers after discovering several strange objects lying on their land.

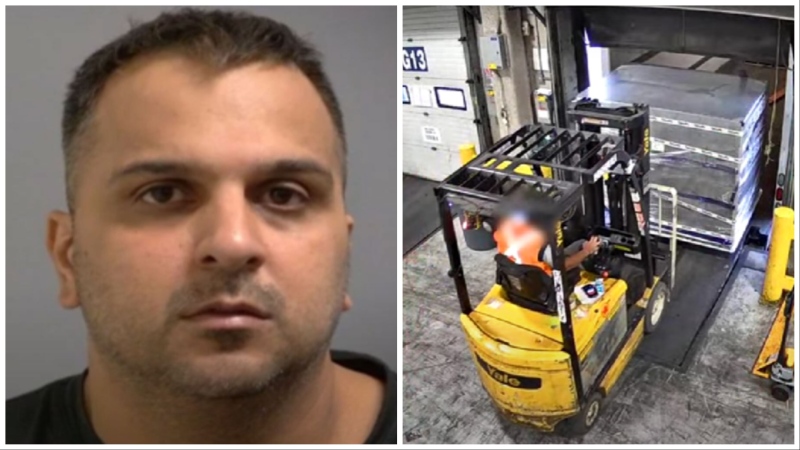

Pearson gold heist suspect arrested after flying into Toronto from India

Another suspect is in custody in connection with the gold heist at Toronto Pearson International Airport last year, police say.

Justin and Hailey Bieber are expecting their first child together

Hailey and Justin Bieber are going to be parents. The couple announced the news on Thursday on Instagram, both sharing a video that showcases Hailey Bieber's growing belly.

New analysis of Beethoven's hair reveals possible cause of mysterious ailments, scientists say

High levels of lead detected in authenticated locks of Ludwig van Beethoven's hair suggest that the composer had lead poisoning, which may have contributed to ailments he endured over the course of his life, including deafness, according to new research.

B.C. man used Bobcat as 'weapon' while chasing away homeless people, judge says

A B.C. man has been convicted of assault with a weapon after using a skid-steer Bobcat to chase two homeless people from his lawn, injuring one of them in the process.

Ontario family receives massive hospital bill as part of LTC law, refuses to pay

A southwestern Ontario woman has received an $8,400 bill from a hospital in Windsor, Ont., after she refused to put her mother in a nursing home she hated -- and she says she has no intention of paying it.

Flat tire on a highway? Here's why you shouldn't try to fix it

If you're cruising down a highway and realize you have a flat tire, you may want to think twice before stopping to fix it on the side of the road.

Miss Teen USA steps down just days after Miss USA's resignation

Miss Teen USA resigned Wednesday, sending further shock waves through the pageant community just days after Miss USA said she would relinquish her crown.

Debate on abortion rights erupts on Parliament Hill, Poilievre vows he won't legislate

A Conservative government led by Pierre Poilievre would not legislate on, nor use the notwithstanding clause, on abortion, his office says, as anti-abortion protesters gather on Parliament Hill.