TORONTO - The Toronto Blue Jays have yet to sign any of their first five selections from this year's draft, and in that regard they're not alone around baseball.

Many of the top picks -- including 15 of the first 20 players chosen overall -- are without a contract as next Monday's midnight deadline for big-league clubs to sign 2009 draftees draws near.

There are several reasons why, among them Major League Baseball's request that teams adhere to its slotted signing bonus recommendations, the natural pushback to that from player agents, and a desire to have someone establish the market.

But the looming cutoff brings two months of game-playing to a head this week, as teams, agents and players hold out as long as they can to get the best possible deal.

"It's changed from the old days when everybody after the draft tried to get everybody signed and get them to play at least rookie ball, or something like that," Paul Beeston, interim CEO of the Blue Jays, said Monday. "It seems to me now virtually all clubs take the summer, so this is the week where it's all going to happen."

Whether that's a good thing or not is up for debate.

This is the third year under the new draft rules establishing a late summer deadline to get picks signed, replacing the old system under which talks could drag on until a week before the following year's draft. And while teams and agents seem to like having a date to work towards, the cutoff also has its drawbacks.

"It's an artificial date, it serves a purpose, but it goes out too far. A better date would have been July 15," said one player agent.

"If there's one thing I've heard consistently through the industry, it's that this two-month period is really just a waste of time. Everybody knows what the positions are, where they categorize their worth on the day of the draft, and there's no new information in the 60, 70 days after. The kids are by and large sitting at home doing nothing when they could be in short-season ball instead."

The loss of development time benefits no one, yet both sides have reason to drag their heels.

Agents like to have precedents they can point to during negotiations, using the contracts of players chosen around them and who play a similar position to establish value.

That often tends to slide in scale from the top picks and this year pitcher Stephen Strasburg, the No. 1 selection of the Washington Nationals, is seeking a record contract that could potentially inflate the bonuses handed to others.

Agents also tend to look for patterns in what a specific team does. For example, if they go over MLB's slotted bonus recommendations for one player, then they might for others.

Teams, meanwhile, have more incentive than ever to take a harder line in talks and avoid straying from slot because under the new rules, if they fail to sign a player taken in the first three rounds, they receive essentially the same pick in the next draft as compensation, while the player returns to draft.

No point, then, in having a gun held to your head when you might even end up with a better talent in the next draft, as the quality of talent varies year to year.

"It's a terrific change," said Beeston, who declined to discuss the state of talks with his team's unsigned picks, other than to say, "things are moving along."

Beeston is personally negotiating the deal with supplemental first round pick James Paxton, a lefty from Ladner, B.C., who is represented by Scott Boras.

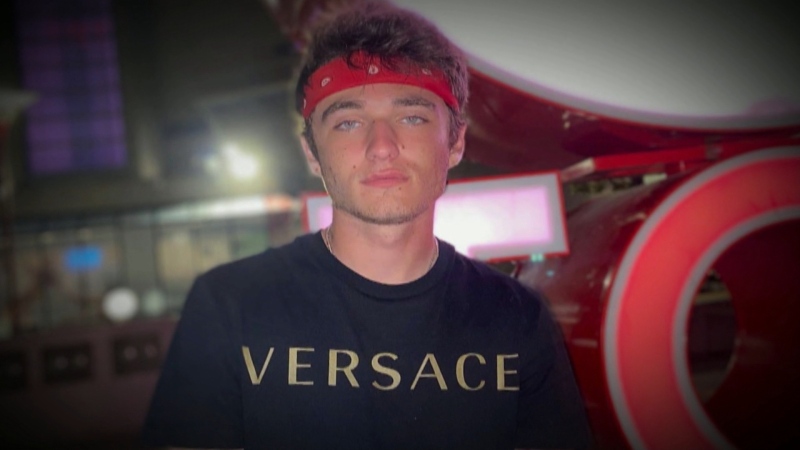

Also unsigned are first-round right-hander Chad Jenkins, second-round lefty Jake Eliopoulos of Newmarket, Ont., right-hander Jake Barrett and outfielder Jake Marisnick, both third rounders.

"There's a game that's got to be played here," said Beeston. "They look for the top guy to fall, and the other guys say, well I'm 50 per cent as good as he is, give me mine."

There are several other points of leverage that can swing talks back and forth.

High school players can use the threat of playing in college to drive up their price, while college players have no place to go but pro ball, giving teams a hammer.

The premium teams are currently placing on developing their own prospects may also create a new dynamic in signing picks, as some believe money is better spent on the draft than free agency, an outlook agents may try to exploit.

"It's kind of a double-edged sword," said one scouting executive. "Certainly the dollars we're talking about in the draft are much less significant than the dollars you're talking about in major-league free agency, so from that standpoint, an extra few thousand here if it gets us the player, maybe that's not a bad investment.

"But draft picks are dangerous, you can spend a lot of money for a guy who'll never spend a day in the big-leagues."

The difficulty in accurately projecting success and the risk of career-ending injury is why Beeston believes draftees need to think hard about their decision. At the end of the day if a player wants to start his career, he must sign with the team that drafts him if he doesn't want to sacrifice a season of development and earnings.

"I wouldn't haggle about it too much because A, I'd want to be in an organization and B, I'd be wanting to play professional baseball, if that's what my career aspirations were going to be, the sooner the better," he said. "I'd worry about making it to the majors and backing up the truck, not $50,000 here or there that's going to make a difference if I sign or not."

That doesn't mean players and agents won't try to get every last penny they can, which is why many negotiations will go right down to the wire.

"Like anything in life, not just sports, people go to the last second to put pressure on and they feel they'll get a better deal at the last moment when pressure's on," said the agent. "That's the way the system's built."