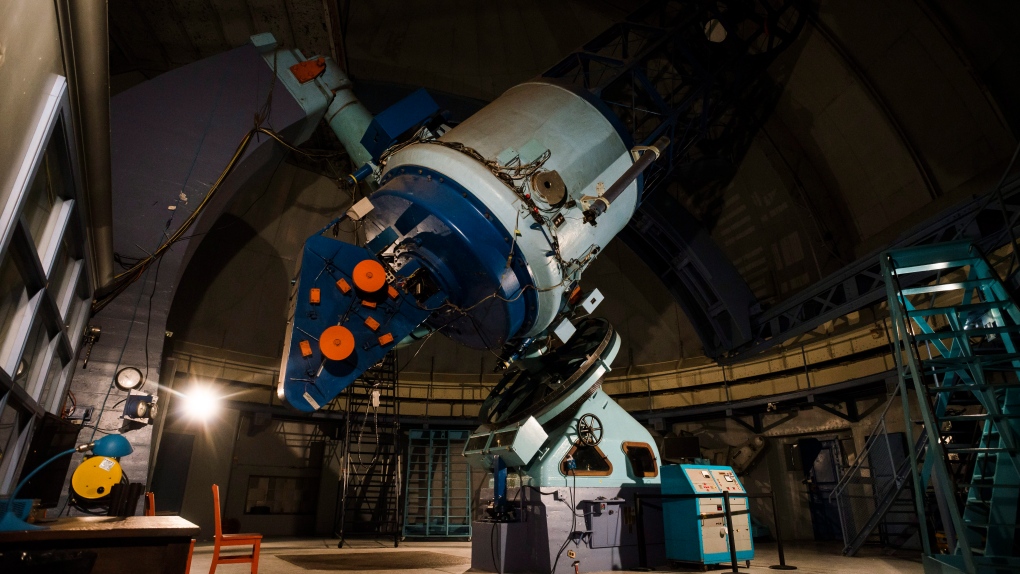

RICHMOND HILL, Ont. -- Randy Attwood remembers visiting the David Dunlap Observatory for the first time as an eight-year-old boy and feeling awestruck as he looked up at the towering 1.88-metre reflector telescope.

He never imagined that more than 40 years later he would deliver lectures about astronomy at the Richmond Hill, Ont., observatory as the executive director of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada.

"When you walk in for the first time into the observatory, you see this massive telescope," said Attwood. "It's overwhelming for an eight-year-old that's for sure...I'm overwhelmed every time I go in there now as an adult. It's an impressive thing to look at."

This summer the observatory, which contains the largest telescope in Canada, reopened to the public after 10 years.

The town of Richmond Hill, which owns the observatory and about half the surrounding property, is for the first time looking to raise awareness of the site and reach the community through programming, said Maggie MacKenzie, the town's heritage centre co-ordinator.

About a 45 minute drive north from downtown Toronto, visitors can every Saturday see the 1.88-metre telescope being operated, star gaze with telescopes set up on the lawn around the observatory, and listen to a guest speaker give an astronomy talk. Once a month on Sundays, tours of the observatory and administration building provide more information about the site's history. A space camp for kids also runs this summer during the week.

Since the University of Toronto sold the property in 2008, there has been years of litigation over its ownership and how it should be maintained, said Ian Shelton, chair of the David Dunlap Observatory Defenders, a group that formed in late 2007 to protect the property and advocate for its upkeep.

"It's a gorgeous place. It's a best-kept secret. People should certainly come visit it," said Shelton, who runs programs out of the observatory and teaches astronomy at the University of Toronto.

"It's a very, very nice place to visit based in terms of its esthetic, but what it represents in terms of Canadian history is just even more spectacular."

The observatory's 61-foot dome weighs 80 tonnes and was built in England and transported by ship to Canada in 1933, said MacKenzie. The telescope was the second largest in the world when the observatory officially opened in 1935.

The property was designated a historic site in 2009 and most of the observatory and administration building is in its original state. The telescope is still functional and hundreds of photographs of planets and constellations are still held in the radio astronomy room.

David Alexander Dunlap was an avid astronomer, philanthropist and founding partner of the Hollinger gold mines. After he died in 1924, his wife, Jessie Donalda Dunlap, donated the property to the University of Toronto as a memorial for her husband. The observatory was then at the forefront of Canadian astronomical research through the university.

"There were a number of prominent astronomers that made this place their home," said MacKenzie.

Helen Sawyer Hogg, one of few female astronomers at the time, started researching in the observatory in the 1930s. She photographed over 2,000 stars, published more than 200 papers and wrote a column for the Toronto Star from the 1950s to the 1980s through her work at the observatory.

Dr. Charles Thomas Bolton was a postdoctoral researcher at the observatory in 1970, and two years later through his research he discovered a black hole.

"But at this time light pollution started to become a problem," said MacKenzie.

She said around the 1970s, as Richmond Hill's population grew and the surrounding areas developed, light pollution became more of an issue, and the astronomers had to adapt their research methods.

For instance, when Dr. Donald Alexander MacRae was the director of the observatory and chair of the university's astronomy department from the 1960s to 1978, he established a radio astronomy program that used a 24-inch telescope in Chile said MacKenzie. She said because of the light pollution, some research would be conducted in Chile and communicated to astronomers at the Dunlap observatory

But despite the efforts, astronomers realized that the telescope wasn't as useful and soon after the observatory was no longer used for research, said Attwood.

"Light pollution is a major problem and it has been for a long time. Light pollution is a real challenge," Attwood said. "It ruins the night sky for people. Very few people have seen a totally dark sky."

Even though the observatory is no longer used for astronomical research, Attwood said the site has always been "a central focus for education and outreach" as the community continually comes by the observatory to look up at the night sky during the summer.

"I couldn't think of a better way to spend an evening."