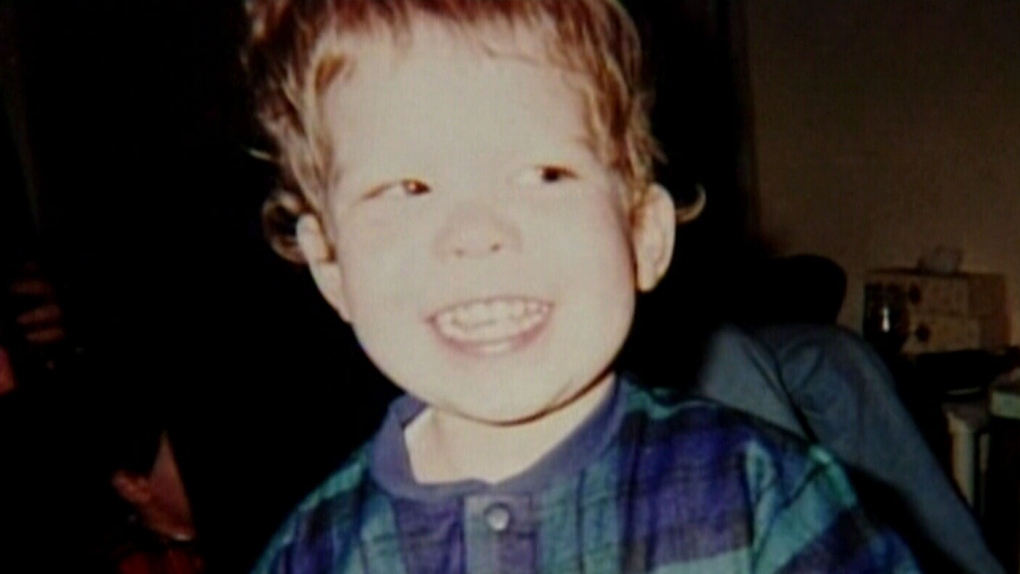

TORONTO -- Allowing a woman convicted of starving her five-year-old grandson to death to take part in a coroner's inquest into the case would only "warp and delay" a process meant to prevent such tragedies in the future, lawyers argued Monday.

Elva Bottineau told the lawyer representing the coroner's office last week that she wished to seek standing at the inquest into Jeffrey Baldwin's death.

She made the request in a phone call from the Grand Valley Institution for Women in Kitchener, Ont., where she is being held, months after sending a letter on the matter through her warden, the inquest heard.

The letter dated Feb. 7 never arrived, said the coroner's lawyer Jill Witkins, but a copy was presented at the inquest Monday.

In it, Bottineau said she wanted to voice her opinions and "put the thruth (sic) out there."

Lawyers for the Toronto boy's surviving siblings and the office of Ontario's advocate for children and youth wasted no time in expressing their objections, saying they feared Bottineau would try to challenge facts established during her criminal trial.

They argued that allowing Bottineau to participate would only slow down the inquest and give a convicted killer another chance to defend her actions after having exhausted all other legal avenues.

Freya Kristjanson, who represents Jeffrey's siblings, said any attempt by Bottineau to minimize her responsibility for Jeffrey's death would be an abuse of process.

"There are many things we still do not know about Jeffrey's death and many things we must inquire into. What we do know -- and what there can be no reasonable dispute about -- is who killed Jeffrey and how he died," she told the inquest.

"Elva Bottineau is a killer who tortured Jeffrey and his siblings while starving him to death," she said.

This is an inquest into Jeffrey's death, she said, "not a soapbox for his killer."

Bottineau and her partner Norman Kidman are currently serving life sentences for second-degree murder in Jeffrey's death 11 years ago.

The inquest has heard that both had a history of child abuse, including separate convictions and various dealings with the children's aid society, something children's aid workers only discovered after Jeffrey's death.

Jeffrey was just 21 pounds when he died -- about what he weighed when he was first sent to his grandparents four years earlier.

Bottineau hasn't formally filed an application for standing yet, but should she go ahead, the inquest will consider her request on Nov. 12.

During the hearing, Bottineau's lawyer should address the risks of abuse of process and delay, Kristjanson said.

Much hinges on whether Bottineau will be able to retain counsel. Lawyer Owen Wigderson said his firm would meet with her Monday to see if it will represent her in the proceedings.

Should that be the case, Wigderson vowed he wouldn't use the inquest "to make speeches for the benefit of my client."

Still, he argued, "It certainly seems that Ms. Bottineau has a connection to a number of the issues that are legitimately being explored here."

He asked the inquest to postpone further testimony by Jeffrey's children's aid worker until the matter was dealt with because whoever represents Bottineau would have to cross-examine the caseworker.

The coroner agreed to hold off any further questioning of Margarita Quintana until at least Tuesday, instead calling the caseworker's one-time supervisor, Lorraine McNamara.

Quintana joined McNamara's team in early 1995, just months after the caseworker opened a file on Jeffrey's mother and father in relation to their daughter, the inquest heard.

At the time, Bottineau was acting as temporary caregiver for Jeffrey's sibling and wished to make the arrangement permanent, even as the child's young parents sought to regain care of the girl, documents show.

A lack of records checks meant children's aid workers didn't look through their own files to discover disturbing details of the pair's past until after Jeffrey's death -- an issue that has taken centre stage at the inquest.

McNamara testified she had only a "vague recollection" of having met the family that year and remembered little of the case as a whole.

Asked whether the agency would have checked the records of any prospective caregiver, McNamara said "there were no regulations or standards."

It would be unlikely in the case of a temporary caregiver, but once there was a possibility of a permanent placement, best practices would likely call for an internal records check, she said.

"It was discretionary... There was nothing to guide us in terms of what we should or shouldn't be doing," she said.

Though many CCAS reports were written before McNamara had oversight of the case, she said she would have reviewed them after taking on the supervisor role.

Yet the agency missed several "red flags" in the documents that cast doubt on Bottineau's suitability as a caregiver and her motivations for seeking custody, said Philip Abbink, who represents some of Jeffrey's siblings at the inquest.

Among them were comments suggesting Bottineau's relationship with Jeffrey's teenage mother had "broken down" and that the two hadn't spoken in months.

That alone should have raised concerns about Bottineau's approach to child care, Abbink said.

McNamara recognized the information "would be important in terms of making decisions" and should have prompted further investigation.