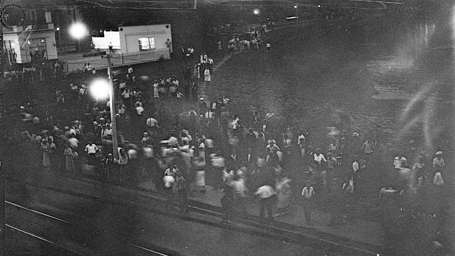

TORONTO -- Joe Black still remembers that warm summer night 80 years ago when he stood watching in shock as one of the worst riots in Toronto's history transformed his favourite neighbourhood park into a battleground.

"There was blood all over the place," said Black, recalling the events that unfolded on Aug. 16, 1933, during a baseball game at the Christie Pits Park in the city's west end.

The game -- between the predominantly Jewish Harbord Playground team and the mostly Protestant St. Peter's Church team -- was almost over, when a group of men unfurled a white bed sheet with a black swastika painted on it.

"When they raised the Nazi flag, all hell broke loose," said Black.

The 87-year-old returned to the park on Sunday for a commemorative baseball game marking the 80th anniversary of what has entered the history books as the Christie Pits Riot.

Cyril Levitt, a sociology professor at McMaster University who has co-written a book about the six-hour riot, said he interviewed a number of players from both teams about 20 years ago.

"The players were largely uninvolved, " he said. "One of them said that their bats disappeared. In other words, people from the crowd grabbed their bats to use as clubs."

Levitt said he examined tax records from Toronto in 1931, which included the resident's religious affiliation, and concluded that north of Bloor Street the population was overwhelmingly Protestant, while further south it was largely Jewish and Italian.

"The park is kind of right at the border of those two ethnic areas of the city and it's not surprising that trouble broke out there," said Levitt.

"It was very easy to get reinforcements for both sides, which I think accounts for the longevity of the riot."

Black said that although the swastika was largely aimed at the Jewish players, Italian immigrants and members of other ethnic groups who felt disenfranchised in Toronto at the time, came to their aid.

"It wasn't just Jewish, it was primarily mostly people that couldn't handle the language," he said.

"You've got to remember that the Italian community was wonderful... in that when they heard that this was going on they came up to help the Jewish boys."

At some point during the melee, Black said the crowd heard that one of the Jewish boys got killed.

"When that rumour went around they filled trucks literally and came up to Christie Pits and of course everything went on."

Nobody died that day, but dozens were injured.

Levitt said a close examination of the local newspapers at the time of the riot shows Torontonians were very well-informed of Adolf Hitler's rise to power and the significance of the swastika as a symbol of hatred, dispelling the notion that the unfurling of the swastika at the game wasn't intentionally anti-Semitic.

"Moving beyond ties to Hitler and the anti-Semitism of the Nazis, there was Ku Klux Klan activity in Southern Ontario also around that time and, basically, they hated everyone that wasn't of British, white and Protestant stock," said Wayne Reeves, chief curator for City of Toronto Museums.

"Catholics were attacked, Jews were hated, blacks were hated, Chinese were hated ... and in 1933 the notion was (that) non-gentiles are not welcome in some of Toronto's key public spaces."

The lack of police presence at the park also intensified the riot, allowed for thousands to participate and highlighted the miraculous fact that no one was killed and only one person was charged for carrying a lead pipe, Reeves said.

"You've got to understand that at that particular time, unfortunately, the police force was not the type of force that we have today," said Black.

"They said it was a bunch of Jewish hooligans that started the whole thing and that was the furthest from the truth."

Levitt said that police were well aware of the fact that tensions were high in the park and were warned that a fight could break out, but instead sent the majority of their force to a union rally.

"There were no more than two or three police officers on hand at the park, the usual contingent, even though the police had foreknowledge of the impending violence," Levitt said.

Toronto police Chief Bill Blair, who also attended the commemorative baseball game on Sunday, acknowledged that the police force has come a long way since the riot.

"I think that we look back on that day as a very dark day, a dark period of time not only in Toronto but in Canadian history and society in general," he said.

"I think there has been an evolution in understanding of the role of the police in dealing with intolerance and hate and certainly I'm very proud of the relationship we currently have with all of the diverse people of this city."

Anti-Semitism still manifests itself in Canada, said Conservative MP Peter Kent, adding that future generations should learn from the mistakes of the past.

"What happened here 80 years ago should be part of the Ontario education curriculum," he said. "It's a very sensitive subject, it's a very dark time in Canada's history and Toronto's history," he said.

Howard English of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs -- one of the groups that organized the commemorative game -- said it's important to reflect on the events that took place that day.

"We're also commemorating how far we've come, the fact that we're light years away from the dark days of 1933, when Hitler took power and when there were signs all over this area saying 'no Jews or dogs allowed,"' he said.

"So what we're doing here is to celebrate how far we've come from, but also to remember those ugly days so that we never revert to those days again."