SARS vs. COVID-19: What we didn't learn the last time

This week, as Ontario records its 1 millionth confirmed case of COVID-19, a senior researcher into the 2003 SARS outbreak says recommendations made to blunt the impact of a future pandemic were not followed.

Four years after SARS killed 44 Canadians and 774 people worldwide, Justice Archie Campbell wrote that the outbreak “taught us lessons that can help us redeem our failures.”

“If we do not learn the lessons to be taken from SARS, however, and if we do not make present governments fix the problems that remain, we will pay a terrible price in the face of future outbreaks of virulent disease.”

For Mario Possamai, a senior advisor to Campbell, who oversaw the report’s creation, the failure of public health officials across the country to heed that warning led to the devastating effects of COVID-19.

“Justice Campbell really laid out a blueprint for tackling a pandemic, like the one we’ve been suffering, in a manner that really was able to address and mitigate the risk in an effective manner,” Possamai told CTV News Toronto.

“And the fact that we’ve blown it, in many ways, I think would have been heartbreaking for him.”

Campbell died the same year the report was released.

In the past 22 months, Ontario has seen 1,001,455 lab confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 11,004 deaths.

Possamai believes those numbers could have been much lower, had the province, and federal public health officials, listened to the key message of the 2007 report: the precautionary principal.

“In the event of scientific uncertainty, like there was for COVID-19 early on, you don’t wait for certainty, you err on the side of caution and you err in a manner that protects health-care workers, workers in general, and the public. We didn’t do that,” Possamai said.

Possamai points to the early days of the pandemic, when he says there were already signs that COVID-19 was an airborne disease, a point he says was ignored at the time.

Public health officials in Canada have shied away from using the term “airborne” to describe how the novel coronavirus is spread. Instead, choosing to focus on preventing the spread of the virus via droplets through mask wearing.

Only in more recent months have provinces and local public health units started to publicly acknowledge that, in light of the highly transmissible Omicron variant, aerosols are likely playing a part in how the disease spreads.

A similar debate took place when SARS made its way into Ontario.

A woman stops to read a sign announcing that the SARS clinic at Women's College Hospital is closed in Toronto on Thursday April 24, 2003. (CP PHOTO/Frank Gunn)

A woman stops to read a sign announcing that the SARS clinic at Women's College Hospital is closed in Toronto on Thursday April 24, 2003. (CP PHOTO/Frank Gunn)

According to the World Health Organization, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, was a virus from an animal reservoir that spread to other animals and first infected humans in China in 2002.

The report notes that there was no consensus on whether the virus was transmitted by large droplets or through airborne particles. However, the report recommended that public health decisions not be driven by the “scientific dogma of yesterday or even the scientific dogma of today.”

“We should be driven by the precautionary principle that reasonable steps to reduce risk should not await scientific certainty,” the report read.

The 2006 SARS Commission also found that many health-care workers contracted the virus after going to another unit to help out, a trend that was seen at the beginning of the pandemic in the province’s hospitals and long-term care homes and continues to this day with nearly 50 per cent of hospital staff across Ontario working part-time.

On top of ignoring the precautionary principle, Possamai said that the amount of available personal protective equipment made available to Canadians at the start of COVID-19 was insufficient.

Dr. David Naylor, co-chair of Canada's National COVID-19 Immunity Task Force and professor of medicine at University of Toronto, chaired the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health and said that their report (separate from the 2006 SARS Commission) also made clear the importance of having and adequate supply of PPE.

“The bigger issue, that I think is being pinpointed, is the one around stockpiles, which really were depleted [at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic] and was a basic principle we had identified in the 2003 report,” Naylor told CTV News Toronto. “We had to be table topping. We had to be on top of contingencies and possibilities. We had to have PPE stockpiles. So that was a bit of a disappointment to put it very gently.”

In a statement to CTV News Toronto, Ontario's Ministry of Health said, "Given the global scarcity of personal protective equipment during the initial stages of the pandemic, the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Government and Consumer Services and partners mobilized quickly to acquire and supply PPE for workers in the health system and other critical sectors."

"We have adapted as the pandemic has evolved and the province currently has a sufficient stockpile and continues to build up its domestic supply," the statement read.

In May of last year, a report by Auditor General Karen Hogan found that at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) was not adequately prepared to respond to the surging demand for PPE, which was a result of decades-long issues with managing Canada’s stockpile of emergency supplies.

Since then, Ottawa has pledged to revisit its supply management and said it would work to use up items before they expire and PHAC also agreed to make a series of changes “within one year of the end of the pandemic.”

And while it appears as though the Omicron-fuelled wave of recent COVID-19 infections appears to be waning, Possamai said he wants to see those who have not followed the warnings of the past take some responsibility for their actions and lack of action.

“We need some accountability. The people who have dropped the ball need to be held accountable for this terrible tragedy,” Possamai said.

With files from Rahim Ladhani, Katherine DeClerq, and Rachel Aiello

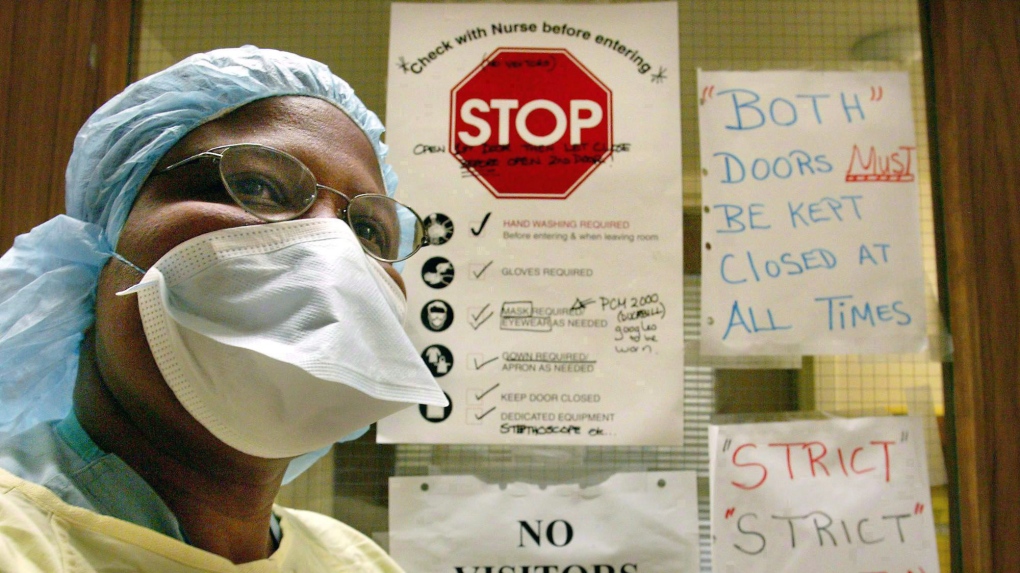

A nurse is shown wearing protective clothing at Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto on March 17, 2003. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Kevin Frayer

A nurse is shown wearing protective clothing at Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto on March 17, 2003. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Kevin Frayer

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Doctors ask Liberal government to reconsider capital gains tax change

The Canadian Medical Association is asking the federal government to reconsider its proposed changes to capital gains taxation, arguing it will affect doctors' retirement savings.

Keeping these exotic pets is 'cruel' and 'dangerous,' Canadian animal advocates say

Canadian pet owners are finding companionship beyond dogs and cats. Tigers, alligators, scorpions and tarantulas are among some of the exotic pets they are keeping in private homes, which pose risks to public safety and animal welfare, advocates say.

Prince William and wife Kate thank public for birthday messages for son Louis

Prince William and his wife Kate thanked the public for their messages which had been sent to mark the sixth birthday of their youngest son Louis on Tuesday.

She was the closest she'd ever been to meeting her biological father. Then life dealt her a blow

Anne Marie Cavner was the closest she'd ever been to meeting her biological father, but then life dealt her a blow. From an unexpected loss to a host of new relationships, a DNA test changed her life, and she doesn't regret a thing.

How quietly promised law changes in the 2024 federal budget could impact your day-to-day life

The 2024 federal budget released last week includes numerous big spending promises that have garnered headlines. But, tucked into the 416-page document are also series of smaller items, such as promising to amend the law regarding infant formula and to force banks to label government rebates, that you may have missed.

Fire engulfs old Edmonton municipal airport hangar

A historical hangar at the former Edmonton municipal airport beside the NAIT main campus was on fire Monday night.

RCMP uncovers plot to sell drones and equipment to Libya

The RCMP says it has uncovered a ploy to sell Chinese drones and military equipment to Libya illegally.

Which foods have the most plastics? You may be surprised

'How much plastic will you have for dinner, sir? And you, ma'am?' While that may seem like a line from a satirical skit on Saturday Night Live, research is showing it's much too close to reality.

'Catch-and-kill' strategy to be a focus as testimony resumes in Trump hush money case

A veteran tabloid publisher was expected to return to the witness stand Tuesday in Donald Trump's historic hush money trial.