Sara van Ravenswaay was devastated when her high school in rural southwestern Ontario was closed last year, months before she was set to begin Grade 12.

The 18-year-old was the kind of student who stayed late after class to engage with teachers and make sure she understood concepts being taught. But now, after having to transfer to a larger school in Grimsby, Ont., van Ravenswaay takes more of her classes online, avoiding spending time in a place where she says she feels like an outsider.

“I've just taken myself away from school as much as possible now because I don't feel like it's a place that I want to spend time,” she said, noting that she has to drive to school now since the bus ride takes more than an hour.

Van Ravenswaay's former school - South Lincoln High School in Smithville, Ont. - was among the rural schools that have been shuttered in recent years due to a dwindling student body.

The closures often force students to commute longer distances to get to class, place them in larger schools where they may feel isolated among already established peer circles, and remove what are essentially community hubs from small towns.

At the same time, some schools in urban centres are bursting at the seams, with students stuck in portables and parents being warned there may not be spots for their kids at their neighbourhood schools.

The issue is one all three main political parties vying to form government on June 7 have vowed to deal with.

As it stands, the province gives money to school boards largely based on enrolment, leaving it up to them to decide which schools to keep open and which to close. But because rural areas and small towns have fewer pupils, they get less cash - including money to heat, power, maintain and repair school buildings.

The Liberal government, wary of criticism that too many schools have been closed, put a halt last year on school boards recommending facilities for the chopping block. However, the moratorium was not retroactive, so schools previously slated for closure aren't off the hook.

Premier Kathleen Wynne has said the Liberals have built or rebuilt one out of every six schools in the province, invested in major repairs to more than 2,900 schools since 2011 and are supporting the use of school space for community hubs.

The Progressive Conservatives and the New Democrats have promised to change a system they say is not working.

Andrea Horwath has said an NDP government would change the school funding formula, consulting with community members, educators and experts on how it should be updated.

Doug Ford's Tories have said they'd uphold the moratorium on school closures until the closure review process is reformed. Guidelines that help that process were recently revamped to better support rural education.

The number of schools that have been shuttered is somewhat unclear.

The Ministry of Education would not say how many schools had closed since Wynne took office in 2013, but in the 2016-2017 school year there were 4,877 public and Catholic elementary and secondary schools in Ontario, down from 4,897 in the 2013-14 school year.

In that time, the province also opened up dozens of new schools.

A 2017 report from the charity People for Education indicated that as of April 30 that year, trustees had voted to close 58 schools, with school board votes pending on another 52 recommended closures at that time. They also proposed opening 25 new facilities. The report suggested the “vast majority” of recommended school closures were in rural areas.

Heather Derks is feeling the impact of a recommended rural school closure firsthand. The public English school her two kids attend in the village of Sparta, Ont., was on the chopping block and will only be taking French immersion students in the fall after the board said there was high demand for that programming in the area.

The change means Derks now has decide whether to send her children - aged eight and 10 - to a Catholic school, consider homeschooling - an unlikely option, she said - or have them commute to an English public school more than an hour away by bus, which she finds unacceptable.

“We lost faith in our government: local and provincial. Especially provincial,” she said of the impact the experience has had on her.

Laurie French, president of the Ontario Public School Board Association, said many factors go into the decision to close schools - it's not all about the money.

“We have to look at, first and foremost, the programming to support student success,” she said.

Small schools aren't able to run as many programs - such as specialized courses in fashion or photography - if they don't have enough students to fill the classes, French said.

In an effort to mitigate the number of school closures in remote areas, the Liberals announced last year the creation of the Rural and Northern Education Fund: a $20-million reserve to help boards keep schools in those regions alive.

There have been other safeguards put in place. The revised guidelines - the ones Ford's Tories would change again - detail extra steps boards must go through before slating rural schools for closure. Those steps include an economic impact study and extra public consultation.

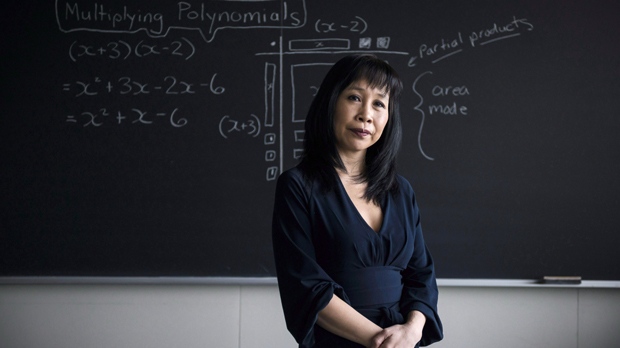

But Mary Reid, a professor of education at the University of Toronto, said the measures are tantamount to a Band-Aid, and not enough to tackle the underlying issue that the funding formula disadvantages small schools, leaving boards with few options other than to continue closures once the moratorium is lifted.

Losing a school can be devastating for small towns, she said.

“It can put a jolt through a small, close-knit community,” she said. “You've got generations of families going to a school, and all of a sudden that school's going to be torn down.”