Officer calls for civilian oversight of Ontario's Indigenous police forces after string of alleged sexual assaults

A Nishawbe Aski Police Service cruiser is seen in this photograph.

A Nishawbe Aski Police Service cruiser is seen in this photograph.

An officer in an Indigenous policing service that has jurisdiction over much of Ontario’s north says its civilian oversight needs an overhaul after a harrowing experience shattered her confidence in the current system and left her unlikely to ever return to what she described as her dream job.

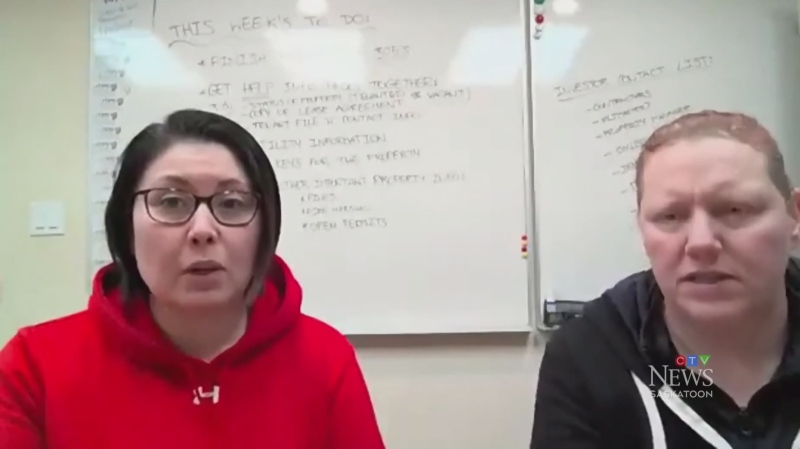

Const. Dawn Loker is calling for the province's civilian police watchdog to be able to do independent investigations of alleged crimes by officers in forces such as the Nishawbe Aski Police Service after she claimed in a $50 million human rights complaint that she was the victim of a series of sexual assaults by another officer.

“He stole me. He took me away from me. And now I don’t have my career, my dream job — it’s gone,” Loker said in an interview with CTV News, wondering if the gap in oversight is another way the Indigenous communities she loved to work in are being let down.

“I started thinking, ‘are there other women out there in these remote communities?’ These communities we work in are vulnerable enough. Has anything like this happened to them? There’s no independent oversight. We need independent oversight,” she said.

NAPS has disputed her account, claiming that its internal investigations and a criminal probe handled by the Ontario Provincial Police showed there wasn’t enough evidence for criminal charges. The other office “steadfastly and vehemently” denied the allegations against him, his lawyer said in a statement.

NAPS was formed by agreement between the Government of Canada, the Government of Ontario and the Nishnawbe Aski Nation in 1994, with a goal of having Indigenous people police their own communities.

It was an alternative to a justice system that incarcerates Indigenous people at higher rates and where as recently as 2018 a review found that systemic racism at the Thunder Bay Police Service was affecting investigations into the deaths of Indigenous people.

Typically in Ontario, the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) is called in cases of death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault by police officers. That agency was formed in 1990 as a civilian alternative to police investigating their own officers.

At the time, the nascent SIU was not included in the NAPS agreements, meaning that they cannot be called in those cases. That's unique among the provinces that have Indigenous police services, said Erick Laming, a criminology professor at Trent University that studies Indigenous policing.

“Ontario is the lone province that operates in that way. It comes down to the set of agreements that the local first nation or the Indigenous community has with the federal governments and whether they want that oversight or not,” he said.

Laming said the Community Safety and Policing Act was passed in 2019 to make it easier for those agreements to be made, but it hasn’t been proclaimed yet, he said.

“It’s a muddy area. Officers receive the same kind of training, but they fall outside the oversight and accountability guidelines,” he said.

Const. Loker started working at NAPS in 2013, after touring the communities with those officers and realizing she wanted to make a difference.

“It really appealed to me and I knew I had to be a part of that,” Loker recalled. “I put the application in and got the job and it was the happiest day of my life when I got that call.”

NAPS has 230 uniformed officers and 40 civilian staff, and polices 34 communities in an area that encompasses some two thirds of the province of Ontario. Its annual reports show that some communities are staffed with as few as two officers.

Loker said in practice that meant she was alone much of the time. After several violent incidents, Loker said the toll of working without backup in a remote community had an impact of severe post-traumatic stress.

“These things happen in policing,” she said. “It’s not the community. It’s just what happens when you’re by yourself and you have a lack of resources.”

She took a leave and returned to work in 2019, and was assigned a partner to help. But she claims in the human rights complaint that her partner sexually assaulted her three times in the police station and in a police vehicle.

Her previous PTSD — and that the two were often the only police officers in the area — prevented her from reporting the incidents sooner, she claimed.

“When PC Loker complained, NAPS did not take steps to protect PC Loker,” the application says, asking for an apology and “to change the culture, structure and systems” of the organization and create an independent system for reporting sexual harassment.

Loker’s lawyer, Gary Bennett, said the changes should include revamping civilian oversight, and allowing the SIU to claim jurisdiction if anyone connected to the incident asks for it.

“Bad things happen when police investigate police,” he said in an interview. “NAPS should have the responsibility to call the SIU and make sure both officers are protected.”

In NAPS’s own filing, the agency does not dispute that resources are an issue, pointing to its agreement that has the federal government contribute 52 per cent of its budget and Ontario contributing the other 48 per cent. Its annual report said its budget was about $56 million in 2022.

“NAPS has been chronically underfunded from the outset. Funding terms have historically been dictated by the federal First Nations Policing Program (FNPP) without significant negotiation,” the response says.

However the agency said it did handle Loker’s complaint appropriately, saying it referred a criminal complaint to the OPP “within hours of learning about the allegations”. The OPP investigation found there was “insufficient evidence to support a criminal charge of sexual assault,” its application reads.

NAPS also commissioned an internal investigation into the events, including hiring a third-party investigator, which concluded that the allegation of discreditable conduct ... is substantiated.”

In a statement, a lawyer for NAPS said in the last five years the agency had not had any circumstances with its officers and civilians that have resulted in serious injury, death or allegation of sexual assault.

Through his lawyer, the second officer involved denied Loker’s allegations in a statement, adding that he would fight his case before the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario.

Messages left with the Nishnawbe Aski Nation and the federal public safety minister, Marco Mendicino, were not returned.

A spokesperson for Ontario’s Solicitor-General said in a statement they “recognize the important role that First Nations policing has in supporting community safety in First Nation communities.”

“The Community Safety and Policing Act (CSPA), once in force, will provide a choice for First Nations to opt in to the provincial policing framework, including provisions relating to policing oversight. The government is open to working with all First Nations and their respective police services, including NAPS, should they be interested in opting into the CSPA. It is the government’s intention to bring the CSPA into force by the fall of 2023 to early 2024,” the statement said.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

LIVE NOW Budget 2024 prioritizes housing while taxing highest earners, deficit projected at $39.8B

In an effort to level the playing field for young people, in the 2024 federal budget, the government is targeting Canada's highest earners with new taxes in order to help offset billions in new spending to enhance the country's housing supply and social supports.

BUDGET 2024 Feds cutting 5,000 public service jobs, looking to turn underused buildings into housing

Five thousand public service jobs will be cut over the next four years, while underused federal office buildings, Canada Post properties and the National Defence Medical Centre in Ottawa could be turned into new housing units, as the federal government looks to find billions of dollars in savings and boost the country's housing portfolio.

Some of the winners and losers in the 2024 federal budget

With a variety of fiscal and policy measures announced in the federal budget, winners include small businesses and fintech companies while losers include the tobacco industry and Canadian pension funds.

From housing initiatives to a disability benefit, how the federal budget impacts you

From plans to boost new housing stock, encourage small businesses, and increase taxes on Canada’s top-earners, CTVNews.ca has sifted through the 416-page budget to find out what will make the biggest difference to your pocketbook.

Police to announce arrests in Toronto Pearson airport gold heist

Police say that arrests have been made in connection with a $20-million gold heist at Toronto Pearson International Airport one year ago.

Teen hockey players arrested for sexual assault following hazing incident: Manitoba RCMP

Three teenagers were arrested in connection with a pair of alleged hazing incidents on a Manitoba hockey team, police say.

'I Google': Why phonebooks are becoming obsolete

Phonebooks have been in circulation since the 19th century. These days, in this high-tech digital world, if someone needs a phone number, 'I Google,' said Bridgewater, N.S. resident Wayne Desouza.

Liberals aim to hit the brakes on car theft with new criminal offences

The Liberals are proposing new charges for the use of violence while stealing a vehicle and for links to organized crime, as well as laundering money for the benefit of a criminal organization.

BUDGET 2024 Ottawa police get $50 million to boost security around Parliamentary Precinct

The Ottawa Police Service will receive $50 million in new federal funding over the next five years to "enhance security" around the Parliamentary Precinct.