TORONTO - Severing a crucial rail artery to disrupt passenger and commercial traffic is an extreme tactic, but can be justified as a way to bring attention to the abject poverty plaguing aboriginal communities, a lawyer representing Mohawk protesters told court Tuesday.

Superior Court was hearing motions about a lawsuit CN Rail (TSX:CNR) has launched against protester Shawn Brant and others over two blockades. A group of Tyendinaga Mohawks shut down the busy Toronto-Montreal corridor of the CN Rail line by raising a blockade in eastern Ontario on two occasions, in April and June of 2007.

CN has sued Brant and others for defying a court injunction during the blockades. The protesters have countersued, claiming the rail line disrupts the Mohawks' way of life and that CN profits from the exploitation of aboriginal people and their land.

CN alleges the blockades caused "significant economic damages due to compounded delays in delivery of bulk commodities and goods." The company has not specified the amount in damages it is seeking.

None of the allegations have been proven in court.

Blockades are "justifiable forms of resistance" and constitute "an assertion of aboriginal land title and an exercise of the duty to protect the land according to aboriginal law," reads the statement of defence.

Outside court, lawyer Peter Rosenthal questioned why CN is pursuing the action.

"People generally recognize now that the way aboriginal people have been treated in history justifies some unusual protest," Rosenthal said.

"The Ipperwash inquiry spoke to that, and other people are beginning to realize that progressively. Why doesn't CN realize that?"

CN officials declined to comment because of the court proceedings.

The Ipperwash inquiry was held to investigate the death of Dudley George, an aboriginal protester gunned down by a police sniper during a 1995 occupation of Ipperwash Provincial Park.

Brant said he believes CN's motive for the lawsuit isn't to recoup its losses, but to send a message to the aboriginal community that there are consequences for their protests. But he said he remains undeterred.

"They can sue me until the cows come home, but it isn't going to stop until the issues of First Nations people are dealt with respectfully, with honour and integrity," Brant said outside court.

It's unfortunate it takes such a disruptive gesture to bring attention to the shameful conditions in First Nations communities, such as boil-water advisories that last for years, he said.

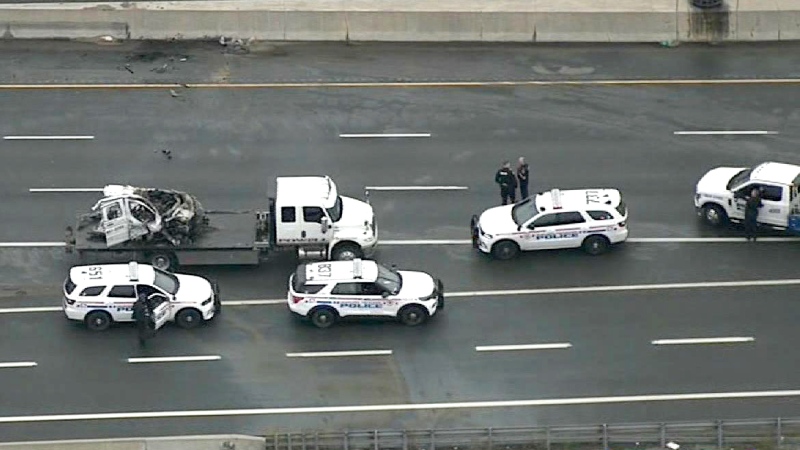

"If I have to go out and shut down the (Highway) 401 or the CN main line in order to have somebody look at our community with some compassion and understand what it's like to live like that for year after year after year," so be it, Brant said.

"It's beyond me why I have to go out and shut down the 401 or the CN main line to have that dealt with."

A court in Belleville, Ont., found Brant guilty in September 2008 of three counts of mischief exceeding $5,000. He had served 57 days of pretrial custody, and was sentenced to time served plus a 90-day conditional sentence and one year of probation.

CN asked the court Tuesday to strike portions from the protesters' statement of defence and counterclaim that the company says are irrelevant to the case, including statements about First Nations people living in poverty.

Rosenthal argued such statements provide the context in which the blockades were established.

CN lawyer Christopher Bredt also asked the court to strike allegations in the counterclaim about trespassing on aboriginal land as an abuse of process. Bredt said Brant cannot claim personal damages on collective rights.

Bredt also noted Brant was not acting on behalf of the band council, as the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte and Chief Don Maracle had publicly admonished Brant and distanced themselves from his actions.

Justice George Strathy has reserved his decision on the motions.