TORONTO -- A woman accused of killing her stepdaughter was the architect of the girl's misery, prosecutors argued Thursday as they recounted for a Toronto jury the harrowing starvation and abuse the teen was subjected to more than two decades ago.

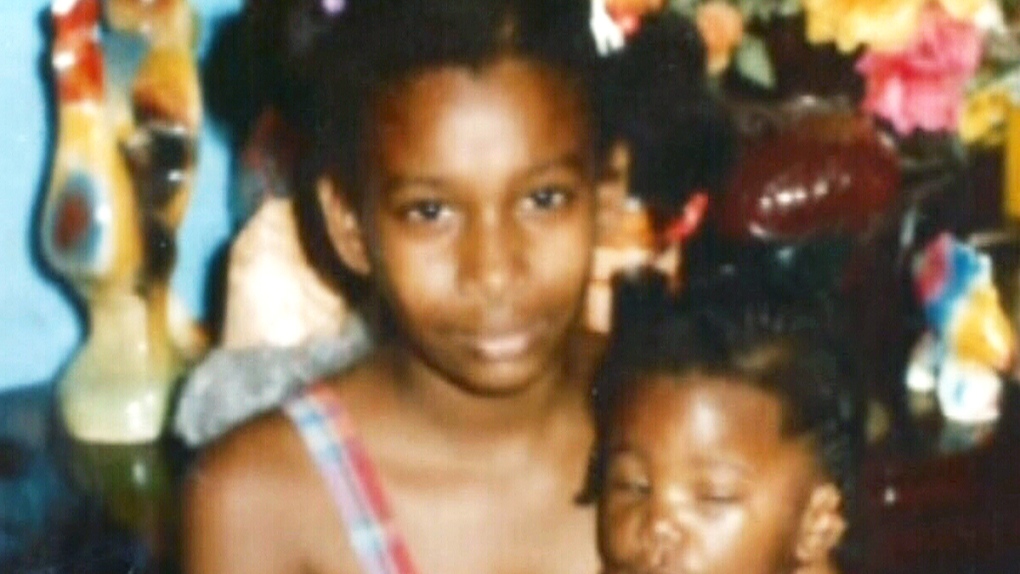

The assertion from the Crown was made in closing arguments at the trial of Elaine Biddersingh, who has pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder in the death of 17-year-old Melonie Biddersingh.

The girl's body was found in a burning suitcase in an industrial parking lot north of Toronto in 1994 but went unidentified for years until 2011, when Biddersingh told an Ontario pastor the girl had "died like a dog."

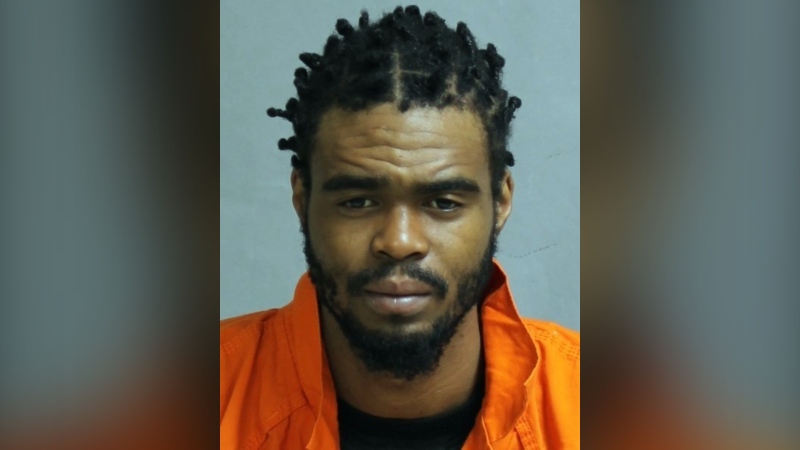

Melonie's father, Everton Bidderisngh, was found guilty in January of first-degree murder in his daughter's death, but jurors at Elaine Biddersingh's trial were instructed to disregard that conviction as "completely irrelevant" to their case.

"Elaine failed in her duties as a parent," Crown prosecutor Anna Tenhouse told the jury. "Elaine was the mastermind and Everton was the fist."

Melonie came to Canada from Jamaica in 1991 with two brothers to live with her father and her stepmother in Toronto. The trial has heard that the children, who had lived in extreme poverty, saw the move as a great opportunity that would lead to a brighter future.

"Instead of dreams, that petite little girl endured abuse and in a short three and a half years she lost weight and she pined away, all at the hands of Elaine and Everton Biddersingh," Tenhouse said.

Melonie's younger brother died in an accident in 1992, the trial heard, and Melonie and her older brother Cleon's treatment worsened significantly over time.

"The children were scared of Elaine," Tenhouse said. "She ruled the house."

The trial heard directly from Cleon, who testified about the prolonged physical and emotional abuse his sister suffered.

Melonie was kicked, slapped and thrown against walls by her father, her stepmother once threw a mug at her head so hard it broke, she routinely had her head put down a flushing toilet, she was deprived of food, made to sleep on the floor, confined to the apartment and eventually chained to the furniture, the trial heard.

"Elaine was convinced Melonie had brought a curse on her home," Tenhouse said. "Elaine played a role in everything that happened in that apartment."

The trial also heard from Cleon that Melonie's physical abuse often followed heated fights between his father and his stepmother.

"Everton never initiated a beating unless it was about something Elaine complained about," Tenhouse said. "Melonie seemed to get the worst of the punishments."

The children were not sent to school, the trial heard. They were saddled with a host of chores, and Melonie in particular had to clean the house, wash clothes in a bathtub and was responsible for caring for Biddersingh's baby girl, the trial heard.

As Melonie's condition worsened under the treatment of her father and stepmother, she cried with pain, had trouble moving and was clearly in need of medical attention, Tenhouse said.

"Everyone in the apartment knew that Melonie was sick," Tenhouse said. "Cleon said Melonie looked like someone who was dying. No one came to Melonie's aid."

Medical evidence called in the trial indicated Melonie was severely malnourished and had 21 healing fractures when she died.

One night, Melonie's father woke Cleon to tell him the girl had run away and he and Elaine were going to look for her, court heard. When the couple returned hours later, they told Cleon to dispose of the cardboard Melonie slept on and the chains used to confine her.

The trial has head that Melonie drowned or nearly drowned, inhaling water shortly before her death.