TORONTO -- Ontario's long-term care minister said she didn't go public early last year with concerns about COVID-19 spreading in nursing homes because she didn't consider herself an authority on the emerging threat.

Merrilee Fullerton faced criticism from all three opposition parties Monday after newly released transcripts showed she told Ontario's long-term care commission she was aware of the dangers the novel coronavirus posed to the sector long before it was declared a global pandemic but kept those concerns within government.

The minister, who is a physician, said while she was worried about a number of issues and discussed them with cabinet colleagues and the province's top doctor, she was no expert.

"As a long-term care minister, I understand my role," she said.

"I'm not the chief medical officer. I'm not a public health expert. I'm not a scientist ... I'm a retired family doctor who cares very deeply about long-term care and the residents and the staff."

Fullerton testified before the Long-Term Care COVID-19 Commission last week, with the transcript posted online Sunday night.

The commission heard that Fullerton and her deputy advocated for stronger measures than what the government was willing to put in place.

"You were ahead of the chief medical officer of health in many respects, from your notes anyway," John Callaghan, the commission lawyer questioning Fullerton, told her.

For instance, Fullerton's notes from the time suggest she was concerned about asymptomatic spread of COVID-19 in long-term care homes as early as Feb. 5, 2020. That possibility wasn't publicly acknowledged by the government until much later.

Fuller told the commission her personal history gave her insights into the situation that other politicians may lack.

"I had suspicions early on only -- well, because I'm a family doctor and spent many years dealing with the elderly," she said. "They may not present with typical symptoms, and so you always have to be watching."

NDP Leader Andrea Horwath said the Fullerton should have spoken out earlier, suggesting that could have saved lives.

"The amount of tragedy that Ontarians have had to deal with as a result of this is unforgivable and it is unforgettable," she said. "So there's a lot of responsibility to go around here."

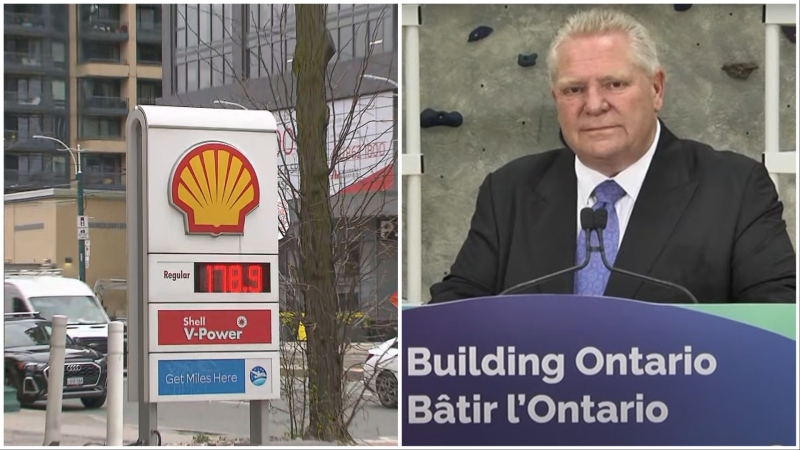

Horwath said Fullerton's testimony also pokes holes in Premier Doug Ford's pledge from the early days of the pandemic to create an "iron ring" around nursing homes.

"This iron ring never materialized, it never existed," she said.

Liberal Party health critic John Fraser said Fullerton should have spoken out publicly.

"It's definitely clear right now that she should have fought harder," he said. "There was a lot at stake."

Fullerton said Monday that she did not consider resigning from her role in protest because she felt she could make urgently needed changes to the sector.

"Why would I resigned from a position where I felt I could be a strong voice and move something that had been neglected for so many years?" she said. "Why would I resign from that duty, from that responsibility, from that obligation?"

COVID-19 has devastated Ontario's long-term care system, causing the deaths of 3,865 residents and 11 staff members so far.

The commission also heard that Fullerton refused to suggest the risk of COVID-19 was low in a video filmed in early March.

Her notes from the pandemic's first wave, read out during the interview, also show that she advocated for locking down long-term care homes before the province did so, and was concerned about staff not wearing personal protective equipment at all times the week before the province made it mandatory.

Fullerton told the commission she was also advocating for essential caregivers to be allowed back into long-term care homes as early as May.

Such caregivers -- usually family members -- weren't allowed back into the facilities until July, and even then, the Ministry of Long-Term Care has said, the rules were being applied inconsistently until adjustments were made in September.

But she said others -- particularly Dr. David Williams, the chief medical officer of health -- said the risk of essential caregivers bringing COVID-19 into the facilities was too great.

"I was very eager to get caregivers back into the homes, because I believe it was well-being and emotional well-being," Fullerton said. "However, others understood differently and had their reasons for understanding the risks that they did, and so it was left."

The commission is set to present its final report on April 30.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 1, 2021.