TORONTO -- The effects of long-term solitary confinement and repeated transfers are among issues that must be explored at an inquest into the death of a deeply troubled teenager who died in custody after repeated episodes of self-harm, the presiding coroner has decided.

In a lengthy ruling on who will have standing at the Ashley Smith inquest, Dr. John Carlisle said the probe also needs to focus on five other areas, including the role of mental-health care and how authorities managed the inmate.

"No one can ever know for certain what was in Ashley's mind just before her death," Carlisle said.

"It seems to me that the jury must hear what evidence there is -- as conflicted as it may be -- of what Ashley said insofar as it was recorded (and) about her intentions regarding the outcome of the self-harming behaviours in which she engaged while in federal custody."

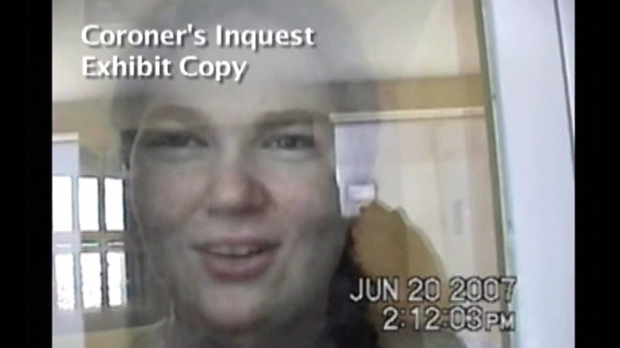

Smith, 19, of Moncton, N.B., choked to death on a strip of cloth in her cell at the Grand Valley Institution for Women in Kitchener, Ont., almost five years ago.

Her family, which believes her death was accidental, welcomed Carlisle's approach as a "breath of fresh air."

"The family has always seen this matter as one in which it was essential that the four corners of the systemic treatment of Ashley Smith was fairly explored," their lawyer Julian Falconer said.

"The family is very comfortable with the direction this matter is taking."

Smith was jailed at age 15 for throwing crab apples at a postal worker and given a 90-day sentence but in-custody incidents kept her behind bars.

In the months before her death in October 2007, she endured forced medication, isolation, and 17 transfers from one prison to another.

"The frequent and repeated transfers may have served to deprive Ashley of what appeared to be an initial willingness to develop therapeutic alliances," Carlisle said.

In addition, he said, authorities appeared to take the moves as "dispensing with the requirement for certain mandatory reviews of continued long-term segregation."

Carlisle said it will be up to the jury to decide whether Smith committed suicide.

As a result, jurors need to explore all circumstances relevant to her death -- including how authorities dealt with her on the day she died -- but that doesn't mean putting her entire life under a microscope, he said.

Still, Carlisle pointed out that Smith suffered severe mental illness, was classified as suicidal, and repeatedly used ligatures in near-fatal self-strangulation.

"Where her custodians are unable to stop those behaviours or respond to them in a way which prevents death, it seems clear that the circumstances of the death give rise to the need for recommendations which might assist the system to avoid such a deaths in future."

Carlisle also pointed out that Smith made numerous complaints during her time in federal custody, and how authorities handled them might have contributed to her sense of hopelessness.

To help the jury, Carlisle expanded the inquest role of Ontario's child and youth advocate beyond issues of segregation to include all youth-custody issues that arise out of Smith's death.

He also granted standing to a group of about 200 patients and former patients of mental-health facilities called the Empowerment Council. The council will be tapped on issues such as the use of restraints and seclusion for people in distress, and how correctional officers deal with the mentally ill.

This is the second inquest called into Smith's death. The first one collapsed last year amid legal wrangling and the abrupt resignation of the coroner.

Several parties, including Smith's family, prison authorities and inmate advocacy groups, who had standing for the first inquest will have standing at this one.