TORONTO - The number of people being charged with impaired driving has plummeted in three-quarters of Ontario communities since 2000, part of a national decline in drinking and driving over the last two decades, an investigation by The Canadian Press has found.

An analysis of provincial criminal charges between 2000 and 2007 found only 13 communities across the province experienced an increase in the number of impaired driving charges.

Across the province, charges received by Ontario's courthouses, posted online by the Ministry of the Attorney General, have been steadily decreasing during the seven-year period, hitting 31,500 charges last year - a decline of 15 per cent from 2000 levels.

At the same time, the number of provincially funded RIDE spot checks have fallen off. Police checked 505,000 cars, boats and snowmobiles last year, compared with 616,000 checks in 2001.

While some say the drop in impaired driving charges indicates people are finally getting the message and avoiding getting behind the wheel while intoxicated, others argue it shows police aren't enforcing the law because of chronic problems with drunk-driving laws.

Cornwall, Ont., police Chief Dan Parkinson, vice-president of the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police, said driving drunk has become as taboo as not buckling your seatbelt.

"Habits have changed," Parkinson said. "It's just not socially acceptable anymore to the degree it was two decades ago to get behind the wheel of a car after drinking."

Indeed, the trend in impaired driving is consistent across Canada. A recent Statistics Canada study found the number of people across the country slapped with impaired driving charges has been cut in half over the last 20 years.

Although the total number of spot checks in Ontario has dropped, Parkinson said provincial funding for RIDE checks recently doubled to $2.4 million and police are as determined as ever to catch drunk drivers.

"This isn't something that is dropping off the table and we're shifting our focus."

The suburban community of Newmarket, north of Toronto, was the Ontario capital for impaired driving charges, leading the province with charges every year between 2000 and 2007. As some communities saw the number of charges cut in half, the Newmarket courthouse experienced a 38 per cent spike over 2000 levels, peaking last year at nearly 2,000 charges.

The Niagara-area community of Welland saw the biggest proportional drop in Ontario, with charges falling to 126 last year from 310 in 2000.

The Ministry of the Attorney General says their figures may differ from those of local police services because the province is tracking charges, as opposed to incidents of crime.

"There is no complacency," said Ontario Attorney General Chris Bentley. "The police, OPP (Ontario Provincial Police) and community city forces are as determined as ever . . . and the laws are as tough as ever."

But some experts say the drop in criminal charges is masking the fact that progress in the fight against impaired driving has stalled.

Robert Solomon, professor of law at the University of Western Ontario, said impaired driving charges may be going down but there has been little change in the number of deaths and injuries at the hands of impaired drivers.

Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) Canada estimates about 60,000 people are killed or injured every year because of impaired driving.

Police are laying fewer formal charges because the laws are too complicated and leave officers drowning in paperwork, Solomon said. It takes police almost three hours to process a single case, only to watch the charges get backlogged and pleaded down in court, he added.

"So basically what you have is a growing de facto decriminalization of impaired driving," Soloman said. "What is supported by the research is the growing reluctance of police to lay the charge and the incredible burden on Crowns."

Other countries, particularly in Europe, do a better job than Canada, Solomon said. Many have lower blood alcohol limits, conduct random roadside breathalyzer testing and automatically test for alcohol following a serious accident, he said.

"They take drinking and driving seriously and they enforce it rigorously," Soloman said. "We don't do that."

Canada, and Ontario, need more effective laws that make it easier for police to target drunk drivers, he added. Without a change, Solomon said more people will die.

Robyn Robertson, president and CEO of the Traffic Injury Research Foundation, said there are a small percentage of drivers that are routinely getting behind the wheel after drinking.

For police, picking those people out is like "looking for a needle in a haystack," she said, and that much more difficult because public attention has been focused on other issues like using a cell phone while driving, street racing or driver fatigue, she said.

"There is more for the police to do," Robertson said. "We're expecting police to ultimately be the protectors out there. (They) can only do so much."

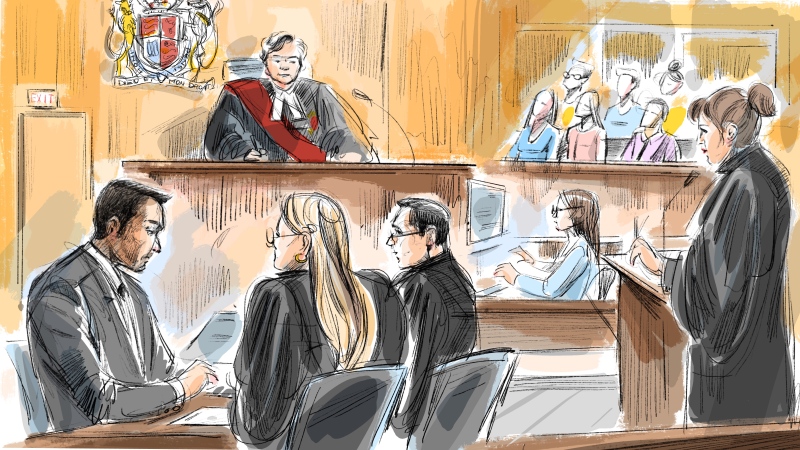

Even if police catch an offender and press charges, Robertson said the court system is clogged. Impaired driving cases make up about one-quarter of a Crown attorney's caseload, she said.

Ontario and other provinces should look to places like Saskatchewan, where police can suspend a driver's licence on the spot for up to 24 hours, Robertson said. Chronic offenders who get slapped with too many suspensions are penalized more seriously, she added.

"It really is an efficient and a quick way to get drivers off the road," Robertson said.

Escalating licence suspensions are a good start, but if governments were serious about stopping impaired drivers, they would allow random, roadside breathalyzer tests, said Margaret Miller, president of MADD Canada.

"Right now, that's a violation of our rights and police aren't allowed to do that," Miller said.

"But really, why shouldn't they be able to stop anybody and ask for a sample at any time? If you're not impaired, you are just helping to protect everybody else."

Still other critics say Ontario could start by fixing a court system that allows people to get away with impaired driving even after charges are laid. Conservative Leader John Tory said impaired driving charges are being reduced to careless driving through "outrageous" plea bargains.

"I think a good start would be for the province to take a much tougher line on actually enforcing the laws and the sentences that are there and plea bargain a lot less frequently," Tory said.

"If the law needs to be fixed, they should do that too."