As rates of near-sightedness, or myopia, soar around the world, some Canadian doctors have begun using eye drops they say can help slow the condition in children before it becomes severe.

In North America, an estimated 42 per cent of the population is myopic, and needs to use glasses or contacts to see at a distance. In Asia, the rate has risen as high as 80 per cent in some areas. Eye specialists aren’t sure why myopia is soaring in some regions but say too much indoor screen and study time could be disturbing normal eye development.

There has never been a way to stop myopia, but now, some eye doctors are experimenting with using a diluted form of a medication that is already on the market.

The drug is called atropine and is currently used to dilate the pupil to treat specific eye conditions. Neither Health Canada nor the FDA in the U.S. have approved atropine for managing myopia in children, but some doctors have begun using it for that use anyway.

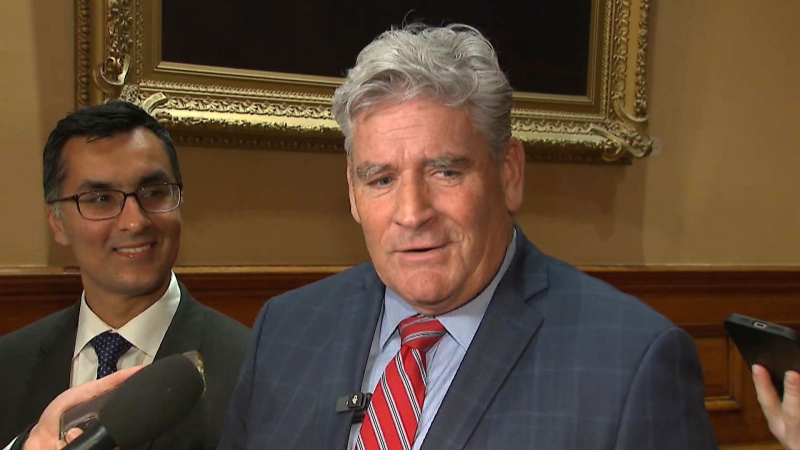

They include London, Ont.-based optometrist Dr. Michael Fenn. He says the problem with myopia that begins in childhood and progresses into the teen years is that it causes the eye to actually grow into an oval. That then increases the risk of sight-threatening conditions such as myopic macular degeneration, retinal detachment and glaucoma.

“So if you can do something to slow the progression of myopia at this stage, you could potentially reduce the risk of potential ocular complications later on in life,” he told CTV News.

Fenn says he was struck by recent research from Singapore that found atropine can slow myopia progression by 50 per cent over five years.

In the study, children were given atropine at a dosage of 0.01 per cent -- which is one-hundredth of the usual dose -- for two years. The dose causes minimal pupil dilation (less than 1 mm), but helped slow myopia progression by about 50 per cent compared to children not treated with the medication.

Fenn has been using the low-dose drops on patients such as Juliana Szucs, 11, for a year. Szucs’ distance vision was once worsening so quickly, she needed to get stronger glasses every six months.

“I was honestly afraid she would be blind, her eyes were changing so quickly,” said her mom Wendy Szucs, who is also nearsighted.

But since Juliana has been using the drops, her prescription hasn't changed.

Fenn says the treatment is effective, inexpensive, and simple, with patients using the drops just once a day at night.

The Singapore study found that of 84 patients treated with .01 per cent atropine for 24 months, only one experienced significant side effects, which included a burning sensation in the eyes. The study also found that about six per cent of patients needed to wear sunglasses because the dilation of the pupil allowed in too much light.

Fenn says there have been “very minimal side effects” among the patients he’s treated, but he notes there have no studies on the drug’s effects over the long term. Scientists also still don't understand how exactly atropine works to arrest myopia, or what happens after its usage ends.

Still, the results of the Singapore study are intriguing enough that scientists have their eye on larger studies planned in the U.K. and Japan next year.

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip