Another death in an Ontario hospital has been linked to C. difficile just as health officials say they are making progress in the battle against a number of the highly contagious outbreaks.

So far, three hospitals have been cleared of outbreaks of the deadly superbug, while seven health centres are still trying to contain them.

Health officials said on Monday that the elderly patient who tested positive for the infection died over the weekend at Guelph General Hospital. Two more cases have also been reported at the hospital since Friday.

Hospitals in Guelph, St. Catharines, Niagara Falls, Welland, Orangeville and Mississauga continue to fight cases. Three hospitals, in Toronto, Hamilton and Napanee, have called off outbreaks.

Ontario's acting chief medical officer, Dr. David Williams, says it could take weeks before outbreaks at the remaining hospitals are considered over. Hospitals must wait 30 days after every case acquired in hospital has cleared before calling off an outbreak.

Eliminating the bacteria can be difficult since the bug produces spores that can contaminate surfaces and that resist most cleaning products. That's in part why C. diff is one of the most common causes of infectious diarrhea in hospitals and long-term care homes.

Health Minister Deb Matthews says experts are working to determine whether all the outbreaks are related.

Of the 100 or so people sickened in the outbreaks, most are being treated with antibiotics. But for patients with stubborn cases or who suffer relapses, doctors sometimes turn to a last-ditch treatment called a fecal transplant.

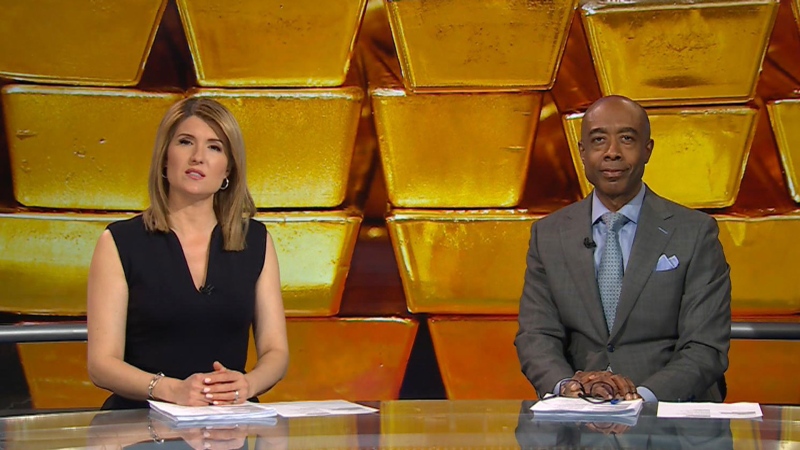

The very idea might make some squeamish, but the treatment can work, says Dr. Christine Lee, the medical director for infection prevention and control at St. Joseph's Healthcare in Hamilton, Ont. A fecal transplant is exactly what it sounds like: doctors take stool material from a healthy patient and transplant it through an enema into the large intestine or colon of a patient with a C. difficile infection.

"The idea behind transplantation is to restore healthy bacteria so that they can combat the disease-producing Clostridium difficile," Dr. Lee explained to CTV's Canada AM Monday.

Unlike other medical transplant procedures, there is no need to find a "match" either for genes or blood type. Anyone can be a donor; they simply need to be screened for infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis.

Potential donors also need to be carefully screened to make sure they don't have a mild C. diff infection that is not showing symptoms. The donor is typically a family member or a spouse.

While C. difficile is widespread, with up to five per cent of the population currently carrying it at any time, the bacteria can overpopulate the intestinal tracts of vulnerable patients, usually those already suffering from other ailments and those taking antibiotics.

The bacteria cause difficult-to-control diarrhea, which can lead to blood infections and sometimes death. In the outbreak in Ontario that began in late May, more than 100 people have been confirmed with infections and 21 have died, most of them elderly.

The idea of fecal transplants isn't new: doctors have reported success with it for decades. But the treatment hasn't been well-studied, so many doctors have been reticent to try it.

Instead, they stick with the usual treatment, which is high doses of antibiotics. That method might seem ironic, since it is often antibiotics that caused the overgrowth of C. difficile in the first place. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatments are effective in about 60 to 80 per cent of patients, says Lee.

For those who don't respond, or who have lingering symptoms or recurring infections, fecal transplants can offer a cure, says Lee.

"The overall efficacy based on our experience has been over 90 per cent success," she says.

Gill Dawson and Elaine Smith, whose parents, Thomas and Margaret Dawson, both died from infections with the superbug within 10 weeks of each other in this latest outbreak, told CTV's Canada AM last week that they don't understand why doctors didn't try fecal transplants to try to save their parents' lives.

But for the most part, the procedure isn't widely available in Canada. Lee explains that a number of infrastructure aspects have to be in place at a hospital that's treating an infected patient.

"First of all, a microbiology lab has to be on site and secondly, you have to have willing and pre-screened donors who are available," she explained. "And third is support from the hospital administration. At St. Joe's, we're fortunate to have all three of those."

With files from The Canadian Press